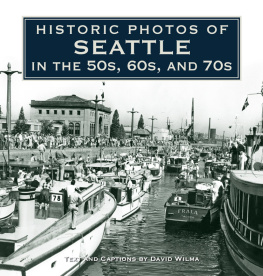

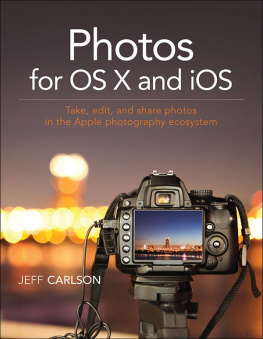

HISTORIC PHOTOS OF

SEATTLE

IN THE 50S, 60S, AND 70S

TEXT AND CAPTIONS BY DAVID WILMA

In 1952, the American Public Power Association held its annual meeting in Seattle at the Olympic Hotel. This view down University Street shows the rear of the hotel and the Metropolitan Theater with its three arched windows. The theater would soon be replaced with a new main entrance to the hotel. During World War II, this portion of University Street was used for war bond rallies and dubbed Victory Square.

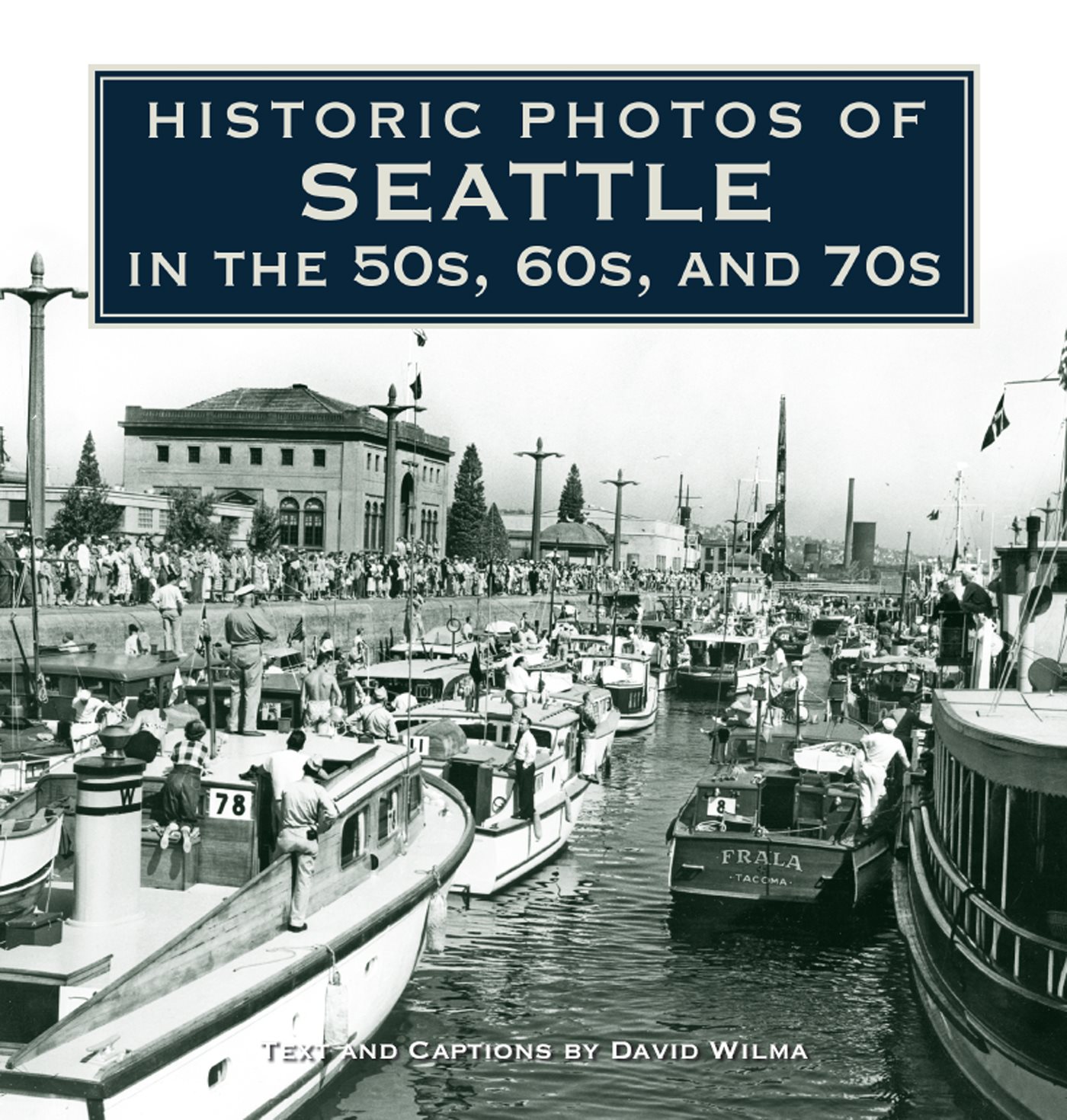

HISTORIC PHOTOS OF

SEATTLE

IN THE 50S, 60S, AND 70S

Turner Publishing Company

200 4th Avenue North Suite 950

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

(615) 255-2665

www.turnerpublishing.com

Historic Photos of Seattle in the 50s, 60s, and 70s

Copyright 2010 Turner Publishing Company

All rights reserved.

This book or any part thereof may not be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2010921719

ISBN: 978-1-59652-596-2

Printed in China

10 11 12 13 14 15 160 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

In August 1962, the Puget Sound region had two fairs to attract visitors, the Century 21 Worlds Fair in Seattle and the more traditional state fair in Puyallup. With some irony, the Worlds Fair was assigned booth space at the state fair, advertising visions of the futureoutside a horse barn.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This volume, Historic Photos of Seattle in the 50s, 60s, and 70s, is the result of the cooperation and efforts of many individuals and organizations. It is with great thanks that we acknowledge the valuable contribution of the following for their generous support:

www.HistoryLink.org

University of Washington Libraries

The Seattle Public Library

Seattle Municipal Archives

Washington State Archives

Rainier Valley Historical Society

Black Heritage Society

Seattle Parks Department

Seattle Department of Neighborhoods

Seattle City Light

Don Sherwood Parks History Collection

The Thunderboat Museum

University Bookstore

Seattle Folklore Society

The Seattle Times

The Bend Bulletin

Paul Dorpat

Alan Stein

Andrew K. Dart

Anacortes History Museum

Unico Properties

Columns magazine

PREFACE

At the end of World War II, Seattle found itself larger, busier, and richer by tens of thousands of new residents who had come to train or build ships and planes for the war effort. On one hand, veterans of the war and Seattleites generally just wanted to return to a normal life in a city that still slumbered as a quiet, even provincial, place to live, but on the other hand they pushed ahead to change the face of society, the economy, politics, and the environment. They needed homes to live in and spent money on cars, furniture, television sets, and, of course, childrenthe postwar baby boom.

Seattle grew in people, territory, and ambition. New cars allowed workers to buy their new homes in distant neighborhoods and suburbs while they worked downtown or out at Boeing. President Eisenhowers Interstate Highway system was intended as a defense measure, but the freeways legislation as spearheaded by Senator Albert Gore, Sr., had consequences almost beyond imagination. Not only did the new, high-speed highways help spur the economy, they changed settlement patterns. Entrepreneurs saw that new shopping centers with acres of free parking were more convenient than downtown and they built Northgate and Bellevue Square. Downtown responded with parking lots and redevelopment plans of its own.

Population grew by almost 25 percent in the 1940s and by another 20 percent in the 1950s, which helped to extend the city limits. After 1960, the number of city residents fell for the next three decades. But if Seattle was smaller demographically after thirty years, it was bigger in every other way. The signature event of this period centered on 184 days in 1962 when the Seattle Worlds Fair amazed everyone. The iconic Space Needle, the sleek Monorail, and hundreds of exhibits showed ten million visitors the promise of the future from space travel and mass transit to computers and something called miniature micro-mail. Celebrities from Elvis Presley to Prince Philip put in appearances.

When the fair closed, Seattle was left with a remarkable piece of property, the Seattle Center, where families frolicked in the International Fountain and where fans could watch professional sports, opera, theater, and rock-and-roll. The U.S. Science Pavilion became the Pacific Science Center where generations of adults and children learned about the natural world of Earth and beyond. The Fair unleashed a spirit of progress, some of it already under way. The Boeing Company produced jet airliners that shrank the world. Researchers at the University of Washington Medical School perfected the artificial kidney and the heart defibrillator, creating an industry with a new name: bio-tech. Transoceanic commerce began using containers to facilitate the movement of freight between oceangoing ships and railroads and trucks.

Not all the progress was greeted warmly by citizens. When Seattle experienced the noise and pollution from Interstate 5 and how the citys charming old buildings (albeit sometimes run down and rat infested) gave way to the scientific efficiency of steel and pre-stressed concrete, residents pushed back. Voters pulled Pioneer Square and the Pike Place Market from the brink of oblivion and they saved the Arboretum from on-ramps and asphalt.

The long hair, drugs, and protest of the sixties rattled Seattles quiet and courteous demeanor. The University District became a magnet for Fringies, later just called Hippies, and their mind-altering substances, throbbing music, and colorful graphic art. After several summers of love (and a few nights of acrimony), the Hippies dissolved into the popular culture and built upon one idea already fashionable in Seattle: environmentalism. Seattle entered the environmental movement in the 1950s by addressing water pollution and garbage disposal. After Earth Day in 1970, citizens and politicians began to call attention to the idea that the rivers, the air, and the mountains were not just there to be consumed like the coal dug out from under Renton and Issaquah. Afterall, the once-abundant salmon came back in fewer and fewer numbers, and except for a few days of sun when the postcards of Seattles picturesque northwest vistas are made, a gray-brown industrial haze edged the region like an ugly bathtub ring.

The eras mix of tradition and change is encapsulated in one image from the Pike Place Market from the early 1970s. A vendor offers a potential customer a free sample of his produce, an everyday transaction in place for generations. But in the 1970s he is shown doing so in sideburns and haircut to the collar.

David Wilma

Next page