William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

HarperCollinsPublishers

1st Floor, Watermarque Building, Ringsend Road

Dublin 4, Ireland

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2021

Copyright Victoria Glendinning 2021

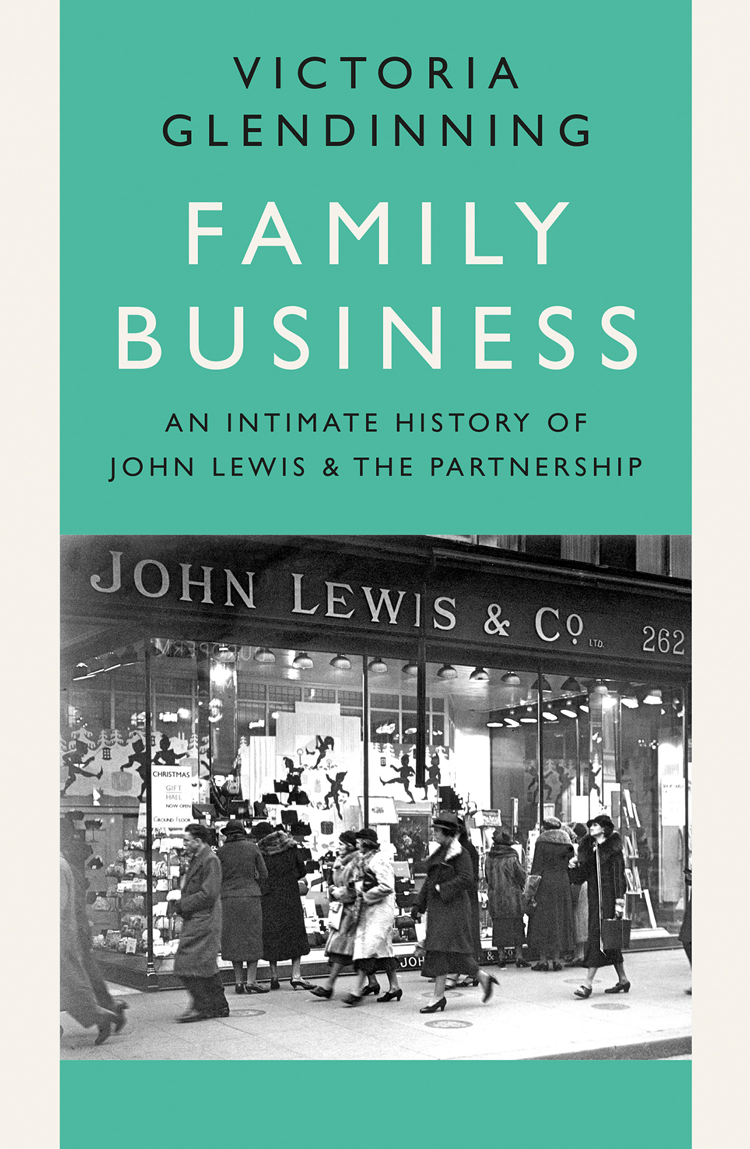

Cover photograph Getty Images

Victoria Glendinning asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Information on previously published material appears .

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008273781

Ebook Edition August 2021 ISBN: 9780008273774

Version: 2022-05-16

FOR PETER LEWIS

This is not a business book nor a corporate history, even though it would never have been written at all if a tempestuous family saga had not been inseparable from the story of the business which dominated their lives.

One day, wandering along Londons Oxford Street, I looked up, and read the familiar name JOHN LEWIS in the familiar lettering. I wondered, who was John Lewis anyway? After some preliminary investigating, I was hooked. John Lewis was an orphan, born into poverty in a small Somerset town not far from where I was living. He made a pot of money and just banked the lot. His obsession with the family fortune distorted his own life and the lives of his wife and children.

I had no idea at the beginning what an extraordinary family I would be taking on. It is a tale of ferocious conflicts, and rows of epic proportions, between John Lewis and his sons, Spedan and Oswald. In Spedans case, these involved shouting, face-slapping, emotional blackmail, a kidnapping and much litigation, between father and both sons and between the brothers, and a spell in prison for Father.

Yet the family never broke up. These were obstinate people of preternaturally high nervous energy. There is glee in Spedans letter to Oswald recounting a physical fight with Father, hurling the office waste-paper basket at his head. Much in this book is borderline comedic; but there is bleak tragedy too.

That particular row was about Fathers treatment of Mother. The story is loud with the voices of women not only Mother but the brothers attachments, wives and families, plus a slew of feisty shop girls, all contributing to the clamour from private letters and diaries, the public record, and the memories of survivors.

If the family story were all, it would be riveting enough. But the personal is embedded in the equally riveting story of the family firm. In 1864 the young John Lewis opened a little drapery business on Oxford Street, in a narrow-fronted shop which had been a tobacconists. Fuelled by prosperity and the rise of an aspirational middle class, thousands of dim little shops were swallowed up or transformed into sumptuous shopping palaces, universal providers, department stores, with glittering plate-glass windows and dazzling floor displays. The new department stores became destinations. Visiting a department store was a sensual experience and an adventure. John Lewis rose on the wave of an unprecedented retail revolution.

His elder son Spedan reacted violently against his fathers self-serving business values. Nevertheless he was a chip off the old block, steeped in the romance of retail. When very young, he elaborated a vision of Partnership of the business as a close community, putting purpose before maximising profits, with every employee having a stake in the enterprise.

Oswald was their mothers darling, destined by her for great things beyond shopkeeping. It was agreed that Spedan was perilously unstable and unpredictable. So he was. He was also single-minded and inspirational. A pragmatist, he saw Partnership as a model for workplace happiness and, as a result, for commercial success. Partnership was to provide an ethical corrective to the inequalities and industrial unrest inherent in unreconstructed capitalism.

The family business did not die with Spedan and Oswald. On the contrary, it thrived. Today, however, the sector is in the throes of another retail revolution. Apparently unassailable department stores, including the iconic John Lewis & Partners, are in limbo. Spedans ideas of Partnership are being put into practice in some form or other by countless grassroots and community enterprises, and may be part of the way forward for the struggling high streets. Sound ideas dont die they survive to meet the good moment.

John Spedan Lewis retired from the chairmanship of the John Lewis Partnership in 1955, at the age of seventy. In the spring of 1959, clearing the attics of Longstock House, his Hampshire home, he decided to take a look at his fathers diaries.

I should have done it long ago, he told his younger brother, Oswald. He had expected just a record of litigation and other matters of business. But the diaries were personal and Spedan himself figured in them, not always in ways he would have supposed. Quarrels and crises which were cataclysmic for Spedan seemed to have affected his father not at all.

Spedan had read up to the year 1922 his father died in 1928 when he dictated an emotional six-page single-spaced letter to Oswald. He had no one at home to confide in. His wife Beatrice was dead. He dictated all his letters, even the most private, to his long-time secretary Muriel, who lived in the house. I have no secrets from Muriel.

Spedans response to the shock of reading the diaries was to burn them. Nearly all of the many volumes that I have found so far are now ashes, and the remainder will be very soon. They would have been a rich picking for muck-rakers and, for an outsider of a much better type, it would have been an extremely tempting combination of the beautiful, the admirable, with the contrary.

In his book Partnership for All (1948), Spedan had written of his father that the conditions of his early life had so overdeveloped in him a passion for accumulating money and a dread of losing it that, where money was concerned, he was like a man driven by a demon. His fathers desire for an heir was not for the sake of the business as a thing in itself but for the sake of the fortune.

Father never retired from the family business. He clung on until he died, in his nineties. In his letter to Oswald, Spedan ascribed their fathers really insane greed of money and power to early hardship: The naturalist, that I was born to be interprets their fathers personality ecologically. He had great qualities of character, and also the nervous energy that Spedan considered essential to success. (He had it himself.) If Father had been reared in a fully civilized home, if he had been to a good school and to a good college, the world would have seen another Mr John Lewis of Oxford Street. Some influences in Fathers development he would not wish changed, though. He had been the delicate boy with several good sisters, and wisdom and backbone are factors independent of culture.

This degree of insight never alleviated Spedans resentment against his father. Reading the diaries just brought back all the old rows, bullyings, misunderstandings and injustices. What a mess life is!