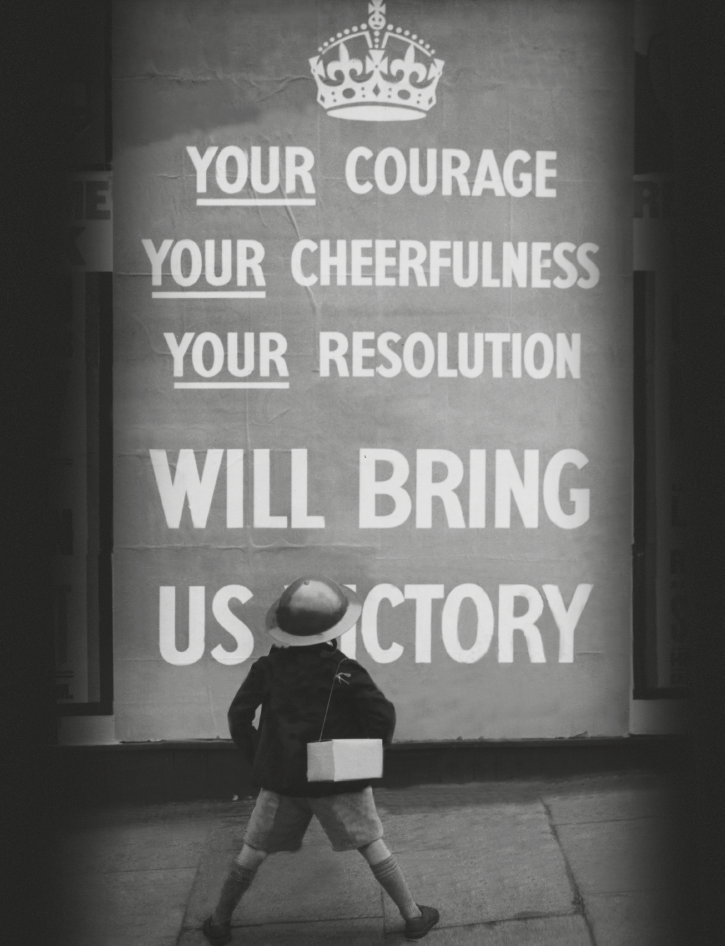

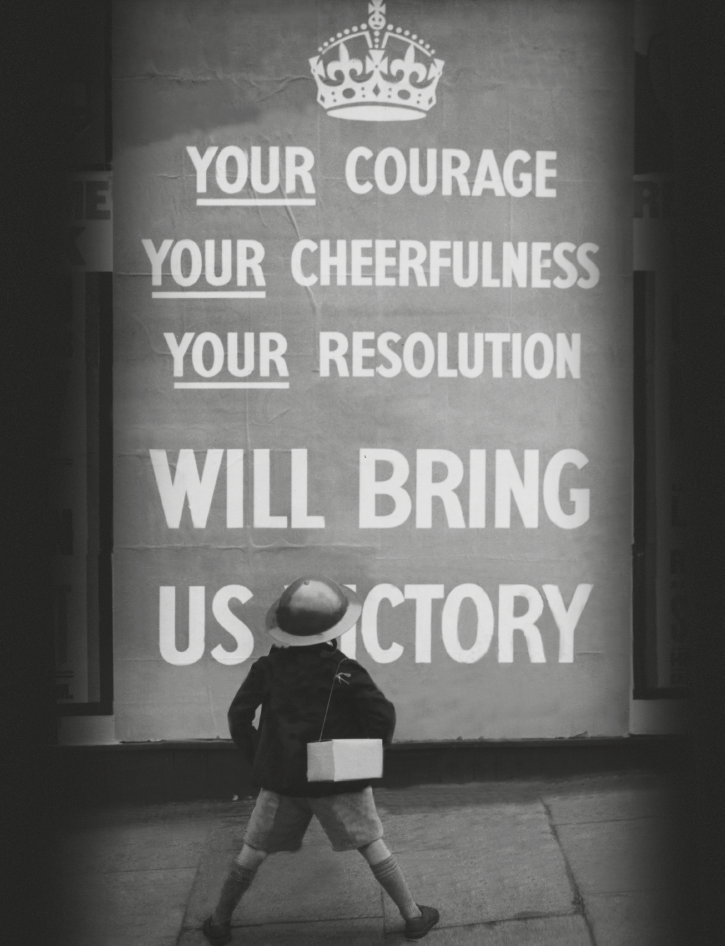

A boy looks at a propaganda poster in London, 1939.

I often wonder why the Second World War seems to get closer as time passes. I was born only twenty years after Hitler shot himself. During my childhood, movies like A Bridge Too Far made it all seem like ancient history. I assumed that becoming an adult and getting older would staple the war into a wooden frame like an old photograph gradually yellowing, looked at less and less, eventually put away.

Time has done the opposite. Now that I am over fifty, I find myself crying at remembrance services. Is it because I understand what sacrifice is, now that I have more to lose? When we recorded a special program about D-day for BBC Radio at the Royal Albert Hall, a veteran of the landings sang a ballad hed written about the day an eyewitness account in song. When it ended, every person in the hall stood. At the end of the show, I thanked the audience, and a man near the rafters shouted back at me, We will remember. And so we do.

When she was doing a report for the childrens newspaper First News, my daughter Martha went to see Barbara Burgess, an elderly woman who lives a stones throw from Marthas grandparents in Devon. The story of their encounter is in this book, so I wont spoil it by repeating the details here. But I accompanied Martha and listened as Barbaras tales of living during the Second World War poured out. And then it struck me: this was not a pensioner talking to a child; it was two nine-year-olds speaking to each other across the decades. Barbara told Martha about the bombs falling on her home in Manchester as if she had never left her hiding place in the cellar. Barbara will not always be here to tell that story. Yet, by listening, Martha and other young First News reporters have framed some precious, startling memories for decades to come. As that lone voice cried out in the Royal Albert Hall, we will remember.

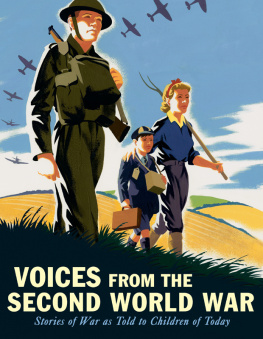

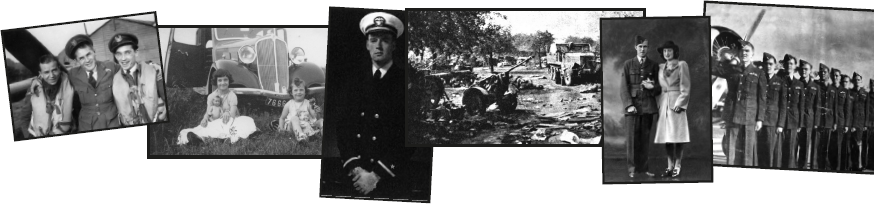

The Second World War changed the course of history. Up to eighty million people died, families were torn apart, and whole cities were reduced to rubble. Now, more than seventy years after the war, survivors share their stories, passing on their memories so that their experiences are never forgotten. Many of the stories in this book were collected by children who interviewed relatives and family friends. Royal Air Force (RAF) rear gunner Harry Irons recounts his first bombing raid on Germany; Anita Lasker-Wallfisch explains how playing the cello in the orchestra at Auschwitz-Birkenau saved her life; and Takashi Tanemori, who was playing hide-and-seek at school in Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, describes what happened when the atomic bomb fell on his city.

So many people alive today have elderly relatives or ancestors who lived through the war. Kate Middleton, the Duchess of Cambridge, explored her own familys story with First News. To find out more about it, she visited Bletchley Park, the center of intelligence gathering in Britain during the war, to meet Lady Marion Body, a veteran who had worked there alongside the duchesss grandmother Valerie Glassborow. Valerie wasnt a code breaker, but had a crucial job in a small section responsible for managing the collection of enemy signals. The duchess learned that her grandmother had been one of the first to know that the war had ended, as she was working the day shift when a signal from Tokyo was intercepted, announcing that the Japanese were about to surrender.

Lady Marion Body tells the Duchess of Cambridge about her time working at Bletchley Park during the war.

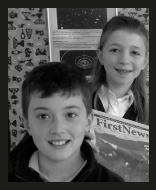

This unique and moving collection of firsthand accounts of the war was first published in England in association with First News, the award-winning childrens newspaper, and the Silver Line, a confidential help line for older people established by Dame Esther Rantzen.

SIR NICHOLAS TAUGHT US MANY THINGS. HE EXPLAINED THAT WE SHOULD ALWAYS TRY TO PREVENT OTHER PEOPLES SUFFERING AND WALK AROUND WITH OUR EYES WIDE OPEN.

Amlie Mitchell and Daniel McKeever interviewed Sir Nicholas Winton, who saved the lives of 669 Jewish children by helping to evacuate them from Czechoslovakia before Germany invaded.

I brought Barbara an onion from my grandpas garden. She used it to explain to me what it was like during the Second World War. To show me how they used to cook it, she boiled it for half an hour. Then she tipped the saucepan, and the onion thudded onto the plate like a wet tennis ball. She covered it in salt and pepper, and spread butter on it. Normally I dont like onions, but this one was different. The butter made it quite easy to eat. It made me realize that even though you think people ate quite disgusting things in the war, they had a way of making them taste nice. After hearing Barbaras stories about the Blitz, I thought the onion tasted very good indeed.

Martha Vine, pictured here with her father, Jeremy Vine, interviewed Barbara Burgess, who told her what it was like to live on rations during the German bombardment of Britain known as the Blitz.

IT WAS AMAZING TO MEET DR. FRANKLAND AND HEAR HOW HE FELT ABOUT HIS LIFE AND THE THINGS THAT HAD HAPPENED TO HIM. I FEEL VERY LUCKY AND WOULD REALLY LIKE TO MEET HIM AGAIN TO HEAR MORE STORIES.

Lucca Williams interviewed Dr. Bill Frankland, who told him about his experiences as a prisoner of war of Japan.

I knew my grandma had been a girl during the war, but I had never spoken to her about it, so interviewing her gave me the chance to get to know her even better. I felt special, as she was sharing personal memories with me that would have been lost forever if I hadnt had this opportunity to chat with her. I have seen many films and read lots of books about the war. Hearing my grandmas memories makes those stories more real to me and helps me relate to them with more sympathy and understanding.