Contents

Guide

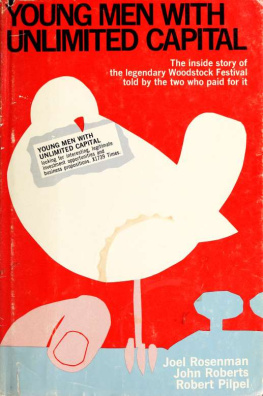

Woodstock began as a plan by Artie Kornfield and Michael Lang to finance the design and construction of a small recording studio in Woodstock, New York. The pair wanted to build a studio in a rural, wooded setting, and they approached entrepreneurs John P. Roberts and Joel Rosenman in 1969 as a means of securing the finance they needed. Roberts and Rosenman were in the process of building the large New York based Media Sound Studio, and while the studio-in-the-woods concept did not appeal to them, the idea of organising a concert in the Woodstock area did. At the time, Woodstock was frequented by artists such as The Band, Bob Dylan and others, and Langs success with the Miami Pop Festival in 1968 provided the experience needed to stage a large event. Roberts and Rosenman agreed to finance the festival, and the four music promoters formed Woodstock Ventures in January, 1969.

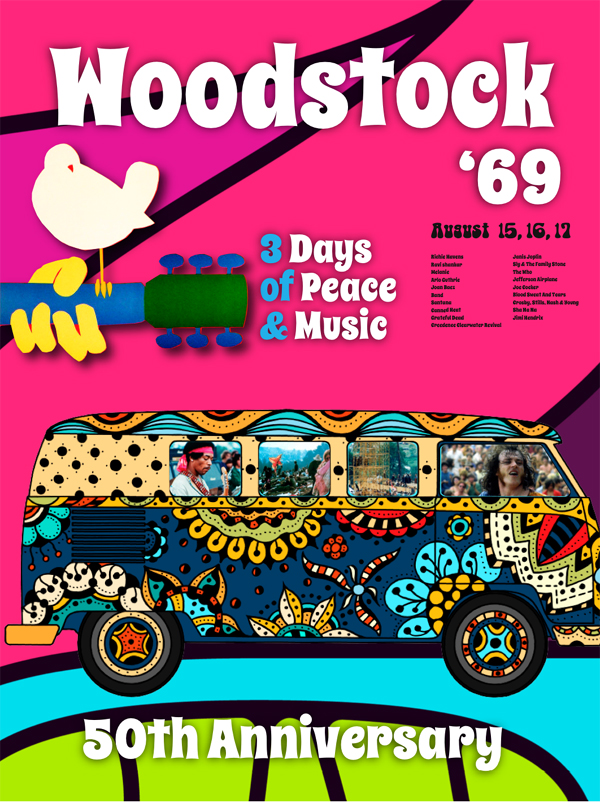

Woodstock Ventures began life as a profit-making venture, and no expense was spared in transforming its Manhattan offices into a psychedelic wonderland for all who visited. While Lang and Kornfield set about finding a suitable venue, Roberts and Rosenman worked hard to sign a big-name group as a means of attracting other big names. It took three months before Woodstock Ventures had its first signed contract, and the group that accepted $10,000 to play for 50 minutes was the hugely popular Creedence Clearwater Revival. With the ink barely dry on the contract, other big-names jumped on board for the August festival advertised as three days of peace and love.

Lang and Kornfield had a more relaxed method of conducting business than Roberts and Rosenman, and following confusion over securing the venue and concern over the amount of money already spent, the latter took over the search. The pair found a 300 acre industrial park in the town of Wallkill and took out a lease for $10,000. As part of the deal, no more than 50,000 people were allowed to attend, but the local population were horrified at the thought of up to 50,000 hippies descending upon them. Under pressure, the Wallkill Town Board then passed a new law that required a permit for any gathering involving more than 5,000 people, and then banned the proposed concert on the grounds of portable toilets failing to meet town codes. While the festival suddenly had no home, it nevertheless gained a lot of publicity as a result of the ban. When an alternative venue was found 45 miles away at the farm of dairy farmer Max Yasgur, it was the Bethel Town Board that was told that there would be no more than 50,000 people attending. It was also the Bethel Town Board that refused to issue formal permits for the festival to go ahead, in spite of work beginning on Yasgurs farm following approval by the towns attorney and its building inspector.

At that point, a stop-work order was issued, leaving the organisers facing ruin in the face of local protests that included placard waving and threats to veto the purchase of milk from the Yasgurs dairy farm. Again, the publicity was a bonus for the festivals organisers, but the acts were booked, time was running out and over 186,000 advance tickets had been sold through New York City record stores and the Radio City Post Office in Manhattan. The cost of tickets was $18, and those who wanted to pay on arrival were to be charged $24.

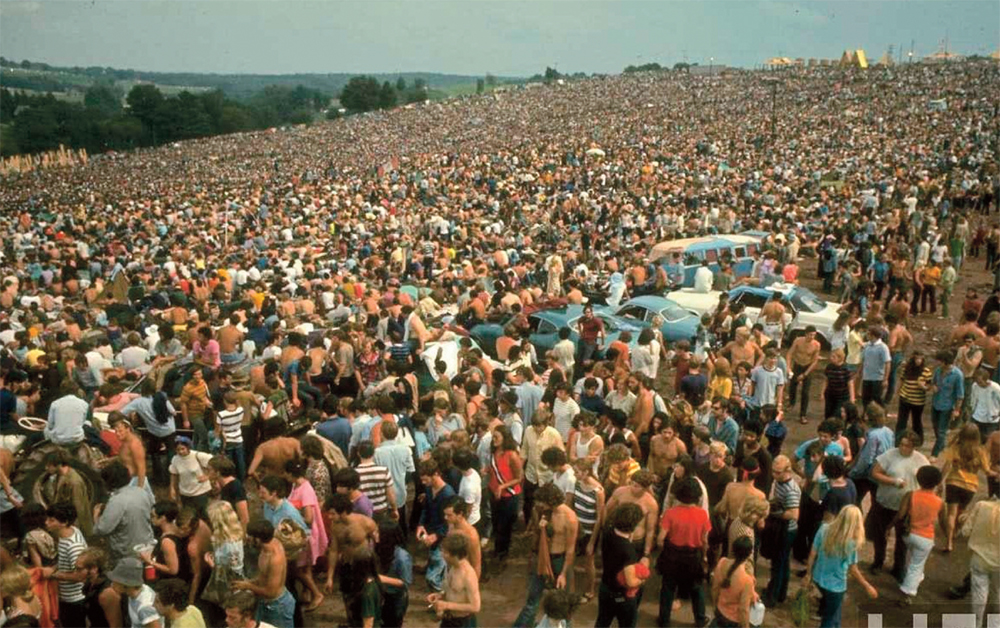

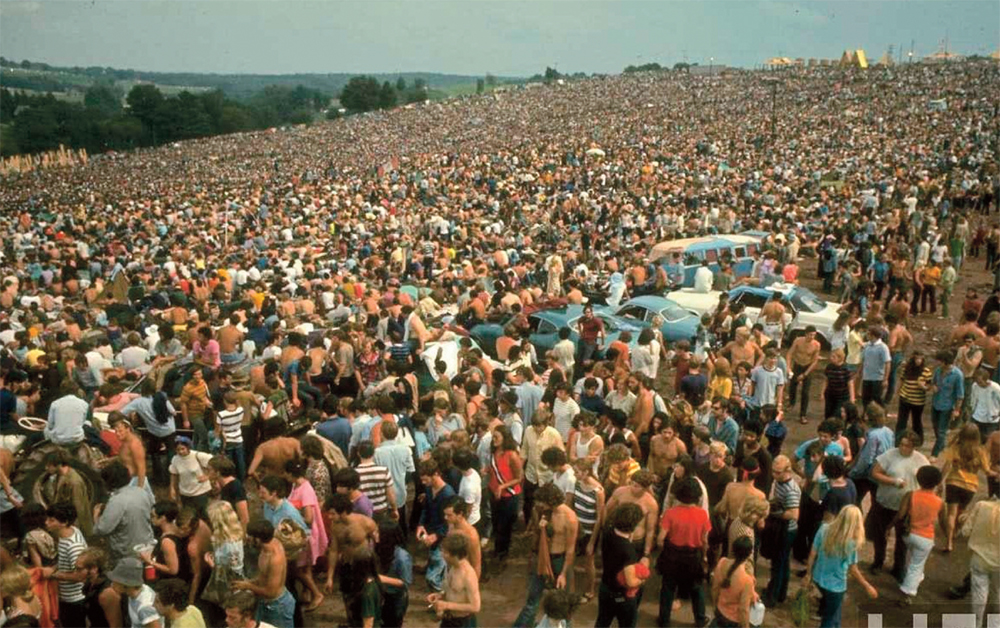

The late change to the venue from Wallkill to Bethel had already placed construction crews under pressure, and the stop work order compounded the situation. Suddenly, the promoters had to decide between completing the fence and ticket booths or completing the stage (which was a turntable affair), as there was neither the time nor the money to do both once the stop work order was lifted. Three days prior to the August 15 event, it was the audience that made the decision when they began arriving early in their tens of thousands and simply walked onto Yasgurs farm - many without tickets. Suddenly, the Woodstock Music & Art Fair became a free festival, and three days of peace and music were enjoyed by more than 400,000 people.

Roberts, Rosenman, Lang and Kornfield were very nearly bankrupted by the unstoppable transformation of Woodstock into a free festival, but they were saved by the recording and film rights that had also been part of their plan. In 1970, the hit documentary Woodstock was released to exceptional reviews. The film cost $600,000 to produce and took in $50 million at the Box Office as well as netting an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.

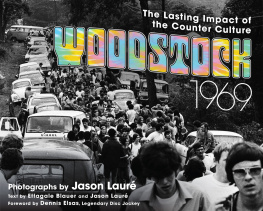

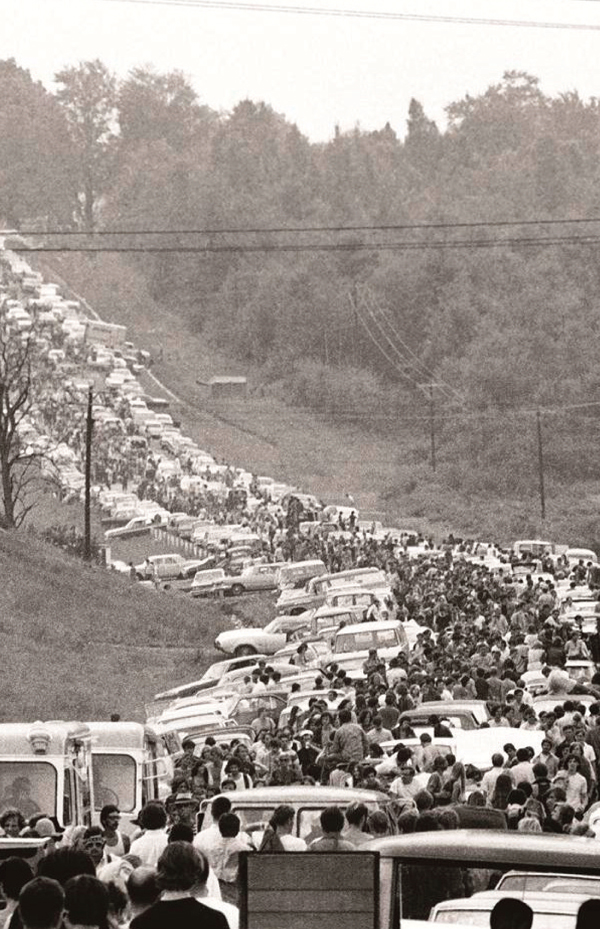

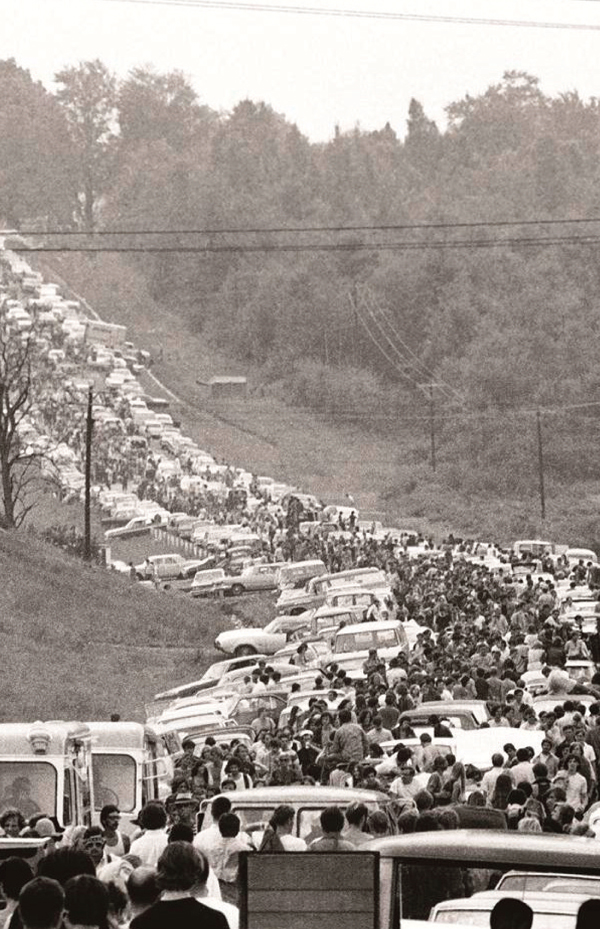

When the massive influx of festival-goers began arriving in Bethel, their presence resulted in an unprecedented traffic jam. Local authorities feared chaos, so no traffic codes were enforced and the build-up continued. Radio stations began announcements as far away as the Manhattan offices of Woodstock Ventures, and television stations tried to discourage people from attending in light of the New York State Thruway reportedly closing. Naturally, very few festival-goers heeded the voice of authority and the crowds continued to build along roads and through fields that had become muddy in light of recent rains. Never before had the roads of New York State been so filled with colour, sound and a sense of peaceful purpose than they did in August, 1969, packed with all manner of bohemian people and vehicles intent upon sharing their love of music and peace to the sounds of 32 performers over four days.

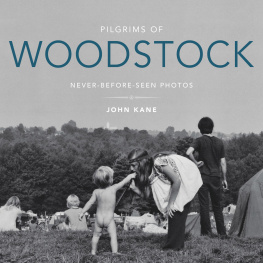

More than 400,000 people were too much for the provided facilities, with food and sanitation in short supply, but the atmosphere was a peaceful one regardless of the privations. The bad weather continued in bursts, but when it was fine, skinny dipping in Fillippini Pond became the order of the day behind the stage at the bottom of Max Yasgurs property. Every square inch of the dairy farmers land was filled with the sights, smells and sounds of a generation committed to peace, love and harmony, and the only fatalities were an accident involving a tractor and a death from insulin usage. At least two babies were born during Woodstock, but no statistics exist to support the number of conceptions.

As the Governor of New York considered calling out the National Guard, and while Sullivan County declared a State of Emergency, the US Air Force provided air transport for the festivals performers. The stage had been completed in time (at the cost of fencing and ticket booths) and sound had been specifically engineered to suit the sound bowl conditions on Yasgurs farm. Speaker columns of 70 feet high sat on hills around the area, each sporting 16 loudspeaker arrangements in a square and known as Woodstock Bins. Power was supplied by three transformers. By 5:00pm on Friday, August 15 1969, Woodstock was ready to begin. By 8:30 am on Monday morning when Jimi Hendrix took the stage as the final act, the world of music would have its most defining moment in living memory, and an entire generation would remember Woodstock for the ensuing half century.