Contents

Guide

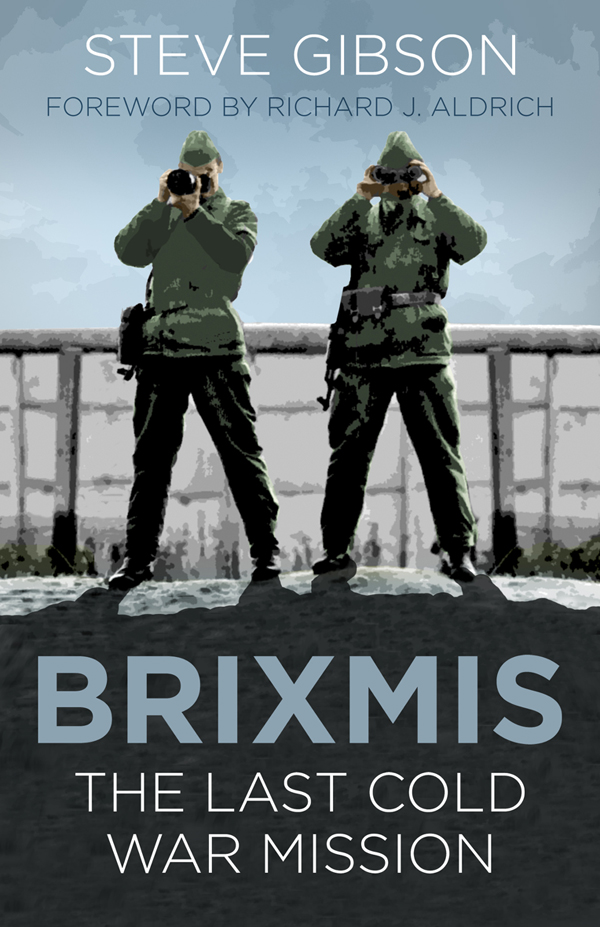

See but dont be seen.

Hear but dont be heard.

First published in 1997

This edition published in 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Steve Gibson 1997, 2012, 2018

The right of Steve Gibson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7524 7766 4

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in India

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am most grateful to the following people, who helped in varying degrees towards the completion of this edition Live and Let Spy and the original edition The Last Mission: Colonel Crispian Beattie CBE, Graham Geary BEM, Colonel Stephen Harrison MBE, Group Captain Mark Knight, Master Aircrew Ray Parnell, Master Air Engineer Bob Hamilton, Ian Passingham, Paul Seagar, Major General Peter Williams CMG OBE, Ernie Wilson, Colonel Nigel Wylde QGM (all former Mission members); other members of the Brixmis Association; Dr Peter Boyden (National Army Museum, London); Dr Bill Durodie (Chatham House); Bernd von Kostka (AlliiertenMuseums, Berlin); Ian Houghton (Sunday Times); Mike Biggar; Ant Edmondson; Paul Lewis-Isemonger; and finally Jo de Vries and Paul Baillie-Lane (The History Press) for bringing this edition to publication, and Sarah Bragginton and Jonathan Falconer (Sutton Publishing) for the original edition.

INTRODUCTION

I kept six serving serving-men

They taught me all I knew;

Their names are What and Why and When

And How and Where and Who.

Rudyard Kipling

The Elephants Child

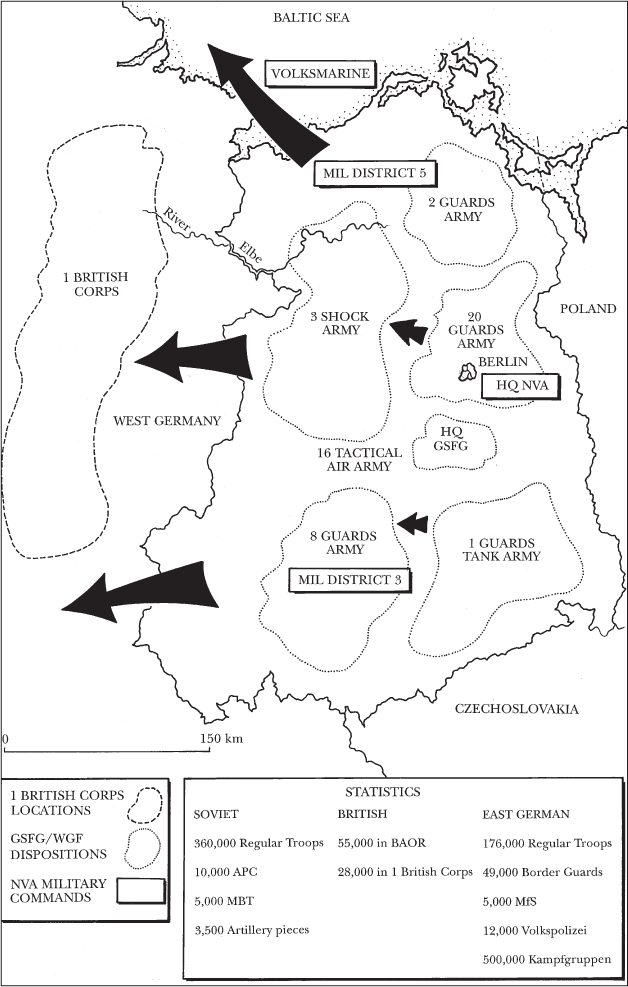

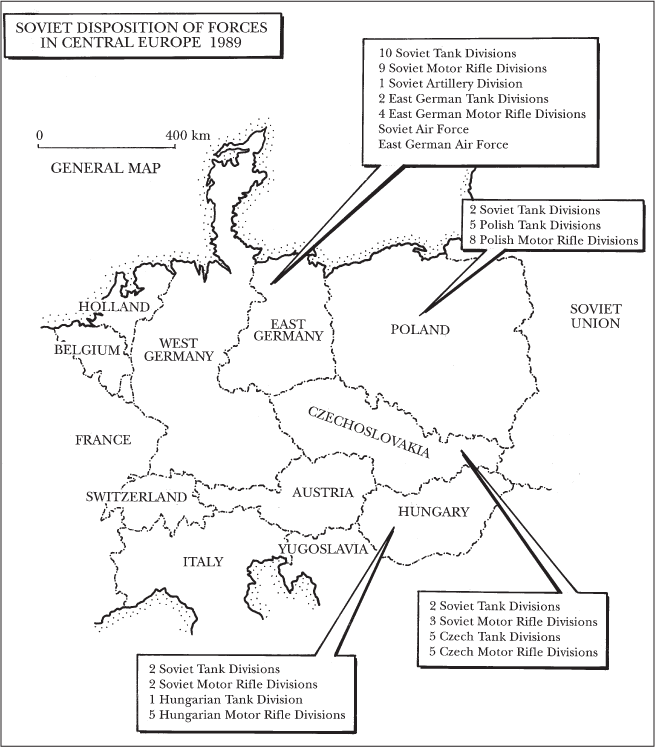

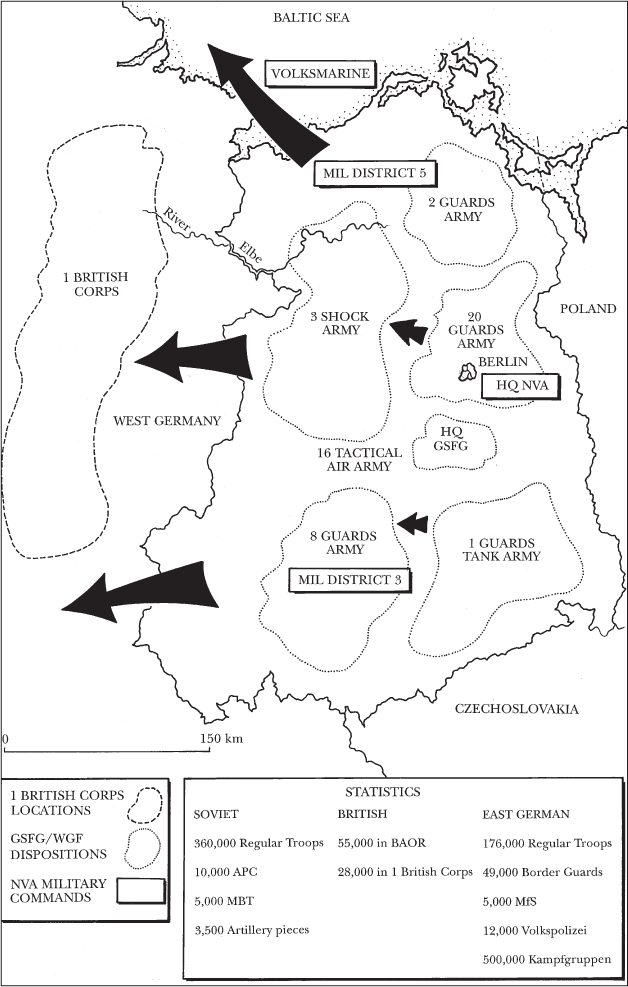

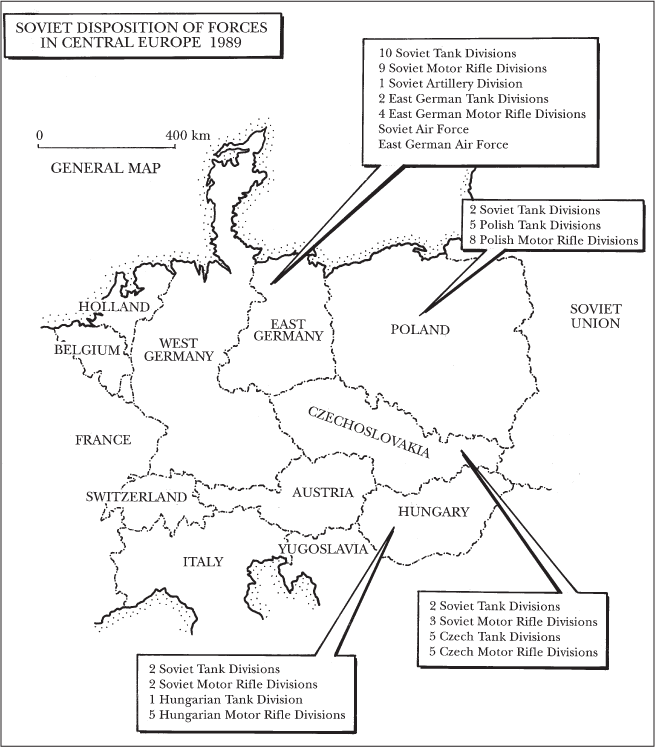

From September 1946 to December 1990, for 365 days a year without a break, a single British Army unit operated behind the Iron Curtain throughout the entire Cold War. This very small, highly specialised and intensively trained group openly collected intelligence against the Warsaw Pact forces based in East Germany. Well beyond the safety of their own front lines, from the Baltic coast to the Czechoslovakian border and from the Inner German Border (IGB) to the Polish frontier they operated unarmed, using Soviet identity cards and in full view of the enemy. Accommodated, fuelled and fed by the Soviets, accredited with an East German bank account, forced to employ East German Stasi agents as staff and working from a watched house in Potsdam, they routinely monitored the composition, strengths, technology, morale and training of the hundreds of thousands of Warsaw Pact troops stationed in East Germany. They would be the first British military personnel to report from the ground that the Warsaw Pact had mobilised against Nato in Europe. Often at enormous risk to their own safety these men were themselves regularly watched, followed, rammed, beaten and shot at during the course of their function as the eyes and ears of the intelligence community beyond the Iron Curtain.

On 16 September 1946, following the division of Germany into the four allied controlled zones and in accordance with Article 2 of the Agreement of the Control Machinery in Germany 1944, Soviet and British Commanders-in-Chief exchanged Military Liaison Missions. The rules of exchange, encapsulated in the Robertson-Malinin agreement, gave licence and flexibility to the, then, new unit. The organisation was titled the British Commander-in-Chiefs Mission to the Group of Soviet Forces of Occupation in Germany, shortened not surprisingly to Brixmis and known generally as the Mission. An equivalent Soviet organisation was similarly ennobled and shortened to Soxmis. Both Missions objective was to maintain liaison between the staffs of the two Commanders-in-Chief and their respective military governments, unhindered and with full diplomatic immunity. Both also had hidden agendas. The fundamental ingredients for a legitimate spying operation had been set in place.

That there was a need to spy rapidly developed out of the early mistrust created between the Soviets and their Western Allies in the immediate postwar struggle to resolve the Germany question. The tacit acquiescence of the Western Allies to the division of Germany and Berlin, its microcosm, was merely rejoined by the bullying, intransigent and frustrating Soviet Union. Germany became the fulcrum of Soviet leverage against the West and the focal point of tension, disagreement and bitterness that was ever the Cold War. Mistrust fuelled suspicion and suspicion had to be satiated. The Mission was ideally situated and, with additional special training, its operatives could answer the questions that face to face encounters and direct questioning between politicians and diplomats could not. Such questions ranged across all aspects of Soviet involvement in the German Democratic Republic (DDR) from industrial output to the latest tank design. The Missions answers gave a comprehensive picture of the day-to-day state of Warsaw pact forces (Soviet and East German), their capabilities, their effectiveness and their readiness for war. At every major political crisis, from the Berlin Airlift in 1948, through the building of the Wall in 1961 to reunification in 1990, the Mission was able to give military analysis and reaction to internationally significant events as they occurred on the ground.

The lucky number 7 myth is dispelled. This tour vehicle was deliberately rammed by a URAL 10-ton truck from the East German Army. It climbed the bonnet and front right-hand side, its momentum carrying it almost completely over the car. The tour NCO was trapped in the wreckage with a badly broken leg and torn ligaments, while the tour officer and driver escaped with shock and heavy bruising. It was one of the sixty or more routine incidents that year. Ironically, unlucky number 7 was recovered by lucky number 13.

The Missions intelligence gathering activities were conducted in three-man, vehicle-borne patrols. These patrols quickly became known as tours in order to disguise any hint of implied aggressive reconnaissance operations. They lasted from two to seven days and covered all manner of military (Army, Air and Naval), industrial and civilian targets that were considered relevant. Anything that tours could see, touch or hear was consumed for the intelligence community. They talked, listened, removed and recorded in an effort to construct the intelligence picture on a would-be enemy. Tasked by all the major intelligence agencies in the Western world, the Mission product was promulgated to its customers for further analysis, comment and wider disposal as seen fit. Simultaneously, Soxmis undertook the same task for the Soviet Union in West Germany. This curious mirror image, coupled with its unique diplomatic status, conferred upon the Mission in theory if not in practice a respect and tolerance that allowed it to operate as it did.