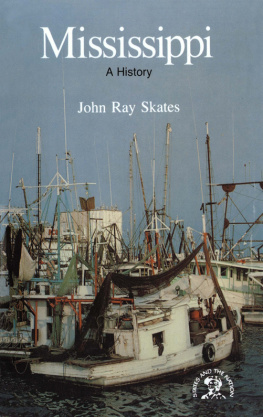

23 Miles and Running

23 Miles and Running

My American Journey from chopping cotton in the Mississippi Delta to Sleeping in the White House

Ty Pinkins

Some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy ofindividuals.

New Degree Press

Copyright 2020 Ty Pinkins

All rightsreserved.

23 Miles and Running

My American Journey from chopping cotton in the Mississippi Delta to Sleeping in the White House

ISBN 978-1-64137-417-0 Paperback

978-1-64137-496-5 Hardcover

978-1-64137-418-7 Kindle Ebook

978-1-64137-419-4 Ebook

To Josephine & Edgar, Willie Mae & Freddie, Sabrina, Joseph, and Rukiya

Contents

A winner is a dreamer who never givesup.

-Nelson Mandela

Preface

The opportunity to write this book came at the beginning of the second semester of my second year in law school. Initially, I questioned the rationale. My law school requirements were already overwhelming. After further thought and some urging from family and friends, I decided to put pen to paper and share my American journey.

This is a personal memoir. It takes a glimpse into my family history, shining a light on many of the events that made me who I am today. It is, however, by no means an exhaustive life timeline. I wrote it for two main reasonsfirst, to create a checkpoint for my family, generations who will come after me, and second, to share my story with others.

Mine is the story of a black kid raised among cotton fields in the Mississippi Delta, yet who somehow grew up to sleep in the White House while working for the first black President of the United States. It is a story of camaraderie and service to country. It is the story of the people who came before me and laid the groundwork to make me who I am today. It is the story of those upon whose shoulders I stand. Most of all, it is one of family, sacrifice, hard work, heartache, and redemption. It is the story of my American journey.

Introduction

I had been runningalone in the darkfor what seemed like forever. As I passed trees lining both sides of the road, each individual stride sent the rhythmic crunch of gravel echoing through the forest. Sweating profusely, chest heaving, and feeling more isolated and alone than ever before, I glanced nervously back over my left shoulder.

Frantically, I thought, Am I still being chased? My pace quickened.

Peering again back into the darkness, I couldnt tell if I was still being pursued. Every now and then, eerie yellow headlights of a passing car provided a momentary sigh of relief, temporarily illuminating the path ahead. The respite was briefgone in an instant as each automobiles glaring red tail lights slowly diminished before vanishing altogether into the distance.

Again, I found myself running alone in the darkness, struggling to make out the path ahead. The only thing I was sure of was that I still had many miles to go until I got there, and I knew I couldnt stopwouldnt stop. Too much was riding on this. Others had fallen behind and gotten caught. Some had even sacrificed themselves and their long-held dreams of making it so I could keep running. Knowing they had given it all up for me was a constant and heavy weight, a thought that perpetually occupied a dimly lit corner in the back of my mind.

Everything depended on me getting to that twenty-third mile. Exhausted, placing one aching foot in front of the next, I kept running alone in the darkhoping I wouldnt get caught like so many others before me.

**

Weve all heard that old saying: Pull yourself up by your bootstraps.

Tossed around casually, it rolls off the tongue light and quick, but it catches you with a slow, heavy weight. Much like the wait we endure as we hold on to the American dream that if you just work hard, you can overcome and achieve anything.

But what happens to the person who has neither boots nor straps?

More than thirty years ago, down in the Mississippi Delta, I met a child. No older than twelve. He lived in a little, old wooden shack nestled between a cotton field and a long, narrow dirt road.

When he walked out of that shack that day, he was shoeless and wore a pair of old tattered cut-off shorts. Drooping loosely from his shoulders was a torn, light blue t-shirt with the word SOJOMAX emblazoned in big, bold red letters. His hair was uncombed and full of tightly curled naps, resembling a congregating colony of bumblebees. Im sure he felt the rocks beneath his bare feet as he slowly made his way down the gravel driveway. His dog, Smokey, followed close behind. It was summer; the sweltering Mississippi sun beat down on the backs of our necks.

At the end of the driveway we crossed that narrow dirt road, his toes sinking into the dust like sand on a beach. We stopped at an old rusted mailbox, leaning as if hanging on for dear life; a slight breeze could have blown it over. He pointed beyond it to a well-worn path winding through waist-high grass down to the creeks edge.

He said excitedly, That there creek is full of big ol catfish. I go fishin there sometimes. We laughed; Smokey peered up at us with a blank stare.

The door of that rusty old mailbox screeched like fingernails on a chalkboard as he yanked it open to retrieve a stack of letters and flip curiously through it. To his surprise one of the letters was addressed to him. Eyes wide, a smile spread cheek to cheek when he realized the letter was from his school. Summer break had begun some weeks earlier, so this must be his final report card.

I just really enjoy learnin, he looked at me and said.

He was a diligent student who rarely missed a day of school. Years of watching Reading Rainbow, whose host LeVar Burton explained the joy of reading, made him fall in love with books. That and Bob Rosss show, The Joy of Painting, held his fascination in an unbreakable grip for hours on end. Every day when he got home, hed go straight to his room to do his homework. He lived in the middle of a cotton field; so, what else did he have to do with his time?

Standing next to that tired, rickety mailbox, he could barely contain himself. He couldnt wait to tell his parents about his final grades, how well hed done, and that hed be moving on to the eighth grade.

In his excitement, he dropped the rest of the letters in the dirt. They rested beside his bare, dust-covered feet; Smokey curiously sniffed each discarded envelope. He ripped open the letter, scanned his report card, and with pride read each grade out loud: A, B, A, B... F?

The expression on his face morphed from excitement to shock, confusion, and finally disappointment.

This cant be right, he exhaled in a slow, low, barely audible whisper.

Though hed done everything rightcompleted all homework assignments, passed every exam, and rarely missed a day of schoolhis math teacher nevertheless gave him an F. The realization that hed have to repeat the seventh grade began to set upon him. In the middle of that dirt road, beneath the weight of that sweltering Mississippi sun, he collapsed to his knees, and he cried, and he began to give up. Smokey plopped down beside him and rested his furry head on his lap as tears dripped down the boys cheeks.

**

Much later, around 8:30 a.m. Monday, August 28, 2017, I found myself alone and over a thousand miles from home. The morning was beautiful, about seventy-five degrees, when I parked my black Cadillac CTS on the corner of First Street and New Jersey Avenue in Northwest Washington, DC. I sat motionless, soulful tunes by Frankie Beverly and Maze drifting from the radio. His voice conjured memories of summer barbecues, house parties, and family reunions held years ago down in Mississippi.