2010 by David A. Powell

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-1-932714-87-6

Digital Edition ISBN 978-1-61121-056-9

05 04 03 02 01 5 4 3 2 1

First edition, first printing

Published by

Savas Beatie LLC

521 Fifth Avenue, Suite 1700

New York, NY 10175

Editorial Offices:

Savas Beatie LLC

P.O. Box 4527

El Dorado Hills, CA 95762

Phone: 916-941-6896

(E-mail) sales@savasbeatie.com

Savas Beatie titles are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more details, please contact Special Sales, P.O. Box 4527, El Dorado Hills, CA 95762, or you may e-mail us at sales@savasbeatie.com, or visit our website at www.savasbeatie.com for additional information.

To my parents, for all theyve given me

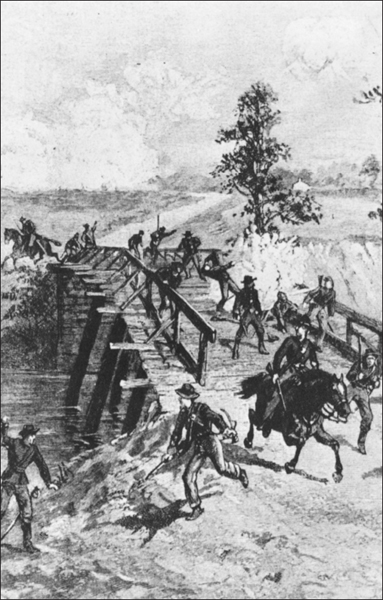

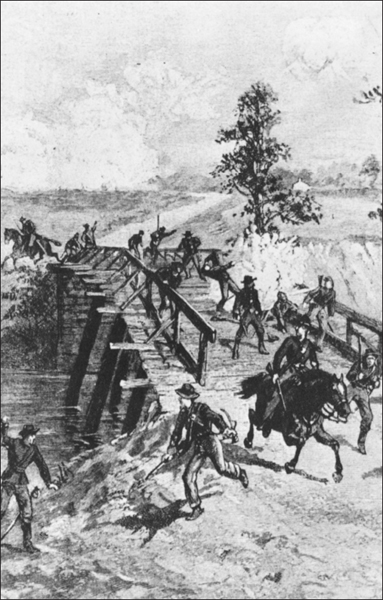

The Fight at Reeds Bridge

Harpers Weekly

Maps

Introduction

In 1998 I wrote an article for Gettysburg Magazine that examined J.E.B. Stuarts famous (or infamous) ride around the Union army in June 1863. Despite the wide variety of literature that existed on the subject, I had some questions of my own to answer about that event. For me, the best way to find answers to my questions has always been to research the topic and write about it. I thoroughly enjoyed the process of analyzing the choices and movements of the men involved in that difficult operation. Along the way I also refined some ideas about the mounted arm.

Civil War cavalry has long been the stuff of romance, though often at the expense of a more hard-headed and realistic appraisal of its place in military affairs. This has become less true in more recent times, as a number of talented historians turn their attention to the importance of cavalry to Civil War campaigns. This is good news for readers of military history because cavalry played a critical role in 19th century operational art, and it needs to be better understood.

In a field dominated by tactical monographs on the various battles of the war, the mounted arm tends to get shoved to the sidelines (or relegated to footnotes), its role in most major battles treated peripherally if at all. The glory and the ink are reserved for the infantry (and to a lesser extent, the artillery). The horsemen guard the flanks, escort wagons, conduct raids, or are held in reserve. Sometimes they fight enemy cavalry or wage rearguard actions, but rarely is cavalry portrayed as critical to the evolution or the outcome of any campaign. This is not only unfortunate but has resulted in an imperfect understanding of the evolution of campaigns and in how we judge operational effectiveness at the army level.

The value and importance of cavalry is demonstrated before battle is joined. Indeed, it is invariably the cavalry that dictates how a campaign unfolds and plays out. William Woods Averell, a Union cavalry general who spent his Civil War years fighting in the Eastern Theater, defined the role this way:

Reliable information on the enemys position or movements, which is absolutely necessary to the commander of an army to successfully conduct a campaign, must be largely furnished by the cavalry. The duty of the cavalry when an engagement is imminent is specially imperativeto keep in touch with the enemy and observe and carefully note, with time of day or night, every slightest indication and report it promptly . On the march, cavalry forms in advance, flank, and rear guards, and supplies escorts, couriers and guides. Cavalry should extend well away from the main body on the march like antennae to mask its movements and discover any movement of the enemy. Without this kind of work, strategy is impossible.

Averell captured perfectly the essentials of the cavalry mission: to scout and screen, to probe and cover. Without effective cavalry, even a talented army commander can suddenly appear operationally incompetent.

In 2009 Savas Beatie published my first book (with David A. Friedrichs) entitled The Maps of Chickamauga: An Atlas of the Chickamauga Campaign, Including the Tullahoma Operations, June 22-September 23, 1863. My first Chickamauga manuscript, however, was finished in 2004 and is the book you are now holding. The more I studied the sources and walked the terrain, the more I realized the important role cavalry played in the fall 1863 campaign to capture Chattanooga. For three weeks that September Federal Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans and Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg played cat and mouse in the mountains of North Georgia, each seeking opportunities to damage and ultimately turn and destroy the other. The mounted arm influenced high command decisions and shaped the course and the outcome of the fighting.

This was especially true for Confederate cavalry. Despite being led by such legendary commanders as Nathan Bedford Forrest and Joseph Wheeler, it did not perform well from the outset. Mounted miscues, mistakes, and outright refusals to follow orders hamstrung the Rebels as Rosecrans turned Braggs flank and nearly severed his supply line. These stunning lapses in the saddle by experienced cavalrymen led directly to Braggs loss of Chattanoogaa critically important logistical and manufacturing hubwithout a major engagement. When Bragg finally regrouped and decided to turn the tables on his opponent, the Army of the Cumberland was not where he believed it to be. The result was the confusing and bloody two-day battle of Chickamauga. Although a tactical success, the fighting was a hollow Confederate victory. Most of the Union army slipped away from the field on the night of September 20-21, 1863, and by doing so avoided destruction. Chattanooga remained in Federal hands and was reinforced. Two months later in November the Southern army was routed from the surrounding hills and shoved back into North Georgia. Bragg, as the commander of the Rebel Army of Tennessee, has traditionally received the blame for these failures. The more I studied the campaign, however, the more I moved away from the simplistic view that it was all Braggs fault.

Failure in the Saddle is the result of this evolution of thought. My intent was to pen an operational analysis grounded in an honest and complete assessment of the role played by Confederate cavalry. My primary focus, therefore, is on mounted operations at the expense of other aspects of the maneuvering and fighting. (A similar study from the Union point of view would offer a fascinating counterpoint to this work, and perhaps one day someone will undertake it.)

My hope is that you come away from this work with a challengedand even changedperspective of the Chickamauga Campaign and the men who waged it and, perhaps, a few new questions of your own.

Acknowledgments

First and foremost I would like to thank my good friend Eric Wittenberg for his generosity in helping me get this book published with Savas Beatie. Eric is an award-winning author and noted cavalry historian in his own right, and the idea for Failure in the Saddle is based at least in part on some of his writings about cavalry in the Gettysburg Campaign. Eric is both a fine historian and a gentleman, and I continue to read eagerly everything he writes. If this book rises to the standard he has set with his own work, I will be content.