ALSO BY MADISON SMARTT BELL

The Washington Square Ensemble

Waiting for the End of the World

Straight Cut

Zero db

The Year of Silence

Soldiers Joy

Barking Man

Doctor Sleep

Save Me, Joe Louis

All Souls Rising

Ten Indians

Narrative Design:

A Writers Guide to Structure

Master of the Crossroads

Anything Goes

The Stone That the Builder Refused

Lavoisier in the Year One:

The Birth of a New Science in an Age of Revolution

Toussaint Louverture: A Biography

Charm City: A Walk Through Baltimore

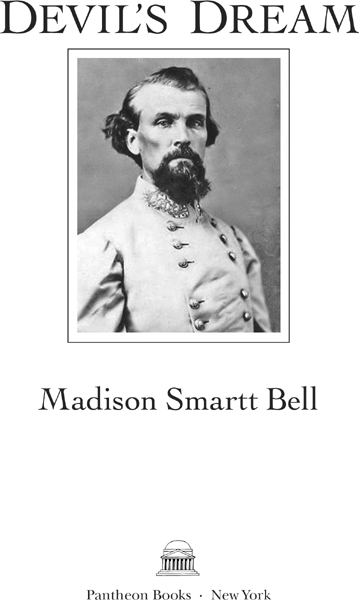

In memory of Andrew Lytle,

with thanks to Dan Frank and Sonny Mehta,

for believing it was a good idea,

and thanks to Jack Kershaw,

for telling me a story

Soldiers do not fight any better because of a good cause or a bad one.

George Garrett, Double Vision

The separation between past, present, and future is only an illusion, although a convincing one.

Albert Einstein, letter to Michele Besso

CHAPTER ONE

July 1861

H HE PASSED THE NIGHT in a canebrake a little way south of the Ohio River, still in earshot of the rivers sluggish flow. Amid the cane he found a raised flat shelf of limestone, harder than sleeping on the ground would have been, but apt to give him some relief from ticks and chiggers or so he hoped. Before he lay down he splashed a little water on the four directions at the edges of the oblong stonenot too much water, for there was a moon, and he didnt want to leave the cover of the cane to fill his canteen from the waters edge.

When he stretched out, the walls of his empty stomach shrunk together, contracting like wet leather as it dried and cracked. Shadows of the slender cane leaves danced over the moonscape of the stone, and the pocks in the surface griped his back and shoulders, or his hip and elbow if he tried to settle on his side, so that he thought he would not sleep, most likely. He heard the crying of a screech owl and watched a bat wing flick across the curved edge of the moonhis eyes as hard and parched as the moon itselfbut then the ancestors were sitting round him in a circle, one plucking slowly on a gut spun and strung across a gourd and another clicking time with two hollow bones against each other. The faces of the Old Ones were hidden from him in shadow, but what came toward him was the face of a white man, hard-favored with his dark eyes bored deep, dark caverns carved away under his high cheekbones and just above the bristly black of the beard that hid his mouth. This white man had the air of a slave-catcher, he thought, and he didnt like the penetration of his look, and yet when the big pale hand spread across his forehead it was a gentle, almost a healing touch.

So he woke up shivering, with no coverlet, only his loose-yoked linsey shirt and nankeen britches. Surprised at his movement, a copperhead poured itself over the edge of the stone and slipped away, rustling the bed of dry cane leaves. The reddish brown braid of it was out of sight before he thought to draw his knife. A bright burst of saliva stung the inside of his mouth. That snake had been big around as his arm

He poured water, pissed off the edge of the rock, took a sip from the canteen, and with the long knife back in the twist of cloth that served him as a belt he stepped down and moved toward the edge of the canebrake, watching closely for the copperhead or his brothers and setting his bare feet down carefully to avoid cane stobs buried in the leaves. Hed had a better kit when he left Louisianaa pack with a spare shirt and pants and a little money rolled up in it, a hat and socks and a pair of stout shoes. All gone somehow along the way. Hed stowed away on a steamboat headed up the Mississippi River, then made the trip across to Louisville, hanging between two boxcars in the dark. In Louisville things had gone against him and he had come away in a great hurry, following the bends of the river but none too closelymaybe as far as Brandenburg, he thought.

At the edge of the woods he found a cluster of new white mushrooms and ate them raw. There were shoots of poke sallet too, which ought to be boiled to drain their poison. They might have been small and new enough to be safe, but he wouldnt risk it. Yesterday he had happened into blackberry brambles and found a few, still reddish, underripe and sour on his tongue and afterward in his stomach. He was still considering the poke weed when a plump rustle in the leaves behind him made him turn, and there was a young blue jay, downed from his nesta windfall the Old Ones must have laid before him. With one movement hed wrung off its head and was catching the first warm jet of blood in the back of his throat. That alone was enough to strengthen him. He still had flint and steel in his pocket but he was wary of smoke from a cook fire, however small. He carried the bird back to the limestone shelf to pluck it, and then ate it raw, all but the viscera and the feet, chewing the little bones and the skull of it most thoroughly.

Encouraged, he walked westward, till he struck a deer trail which he then began to follow. The trail meandered roughly along the same course as the river, now and then coming in sight of it, through a gap in the trees. There were vast clearings with corn just beginning to tassel, south of his way, in the direction of Brandenburg. In the end he might gain the Mississippi again, but that would be days, on his bare feet. And there were soldiers beginning to move in these parts, both the gray and the blue. When war became general he could make his own way, but this circling suspicion was hard for him to navigate.

He began to know that he was being watched, by nothing human though, he thought. He stopped moving, hand on the grip of his knife, and looked, barely breathing, only his eyeballs moving. A doe, a big one, between the river and the trail. Melting brown eyes turned on him through a cluster of black oak and maple leaves and the pale slender leaves of the cane. When he dropped his hip to free the knife she was up and away, the white tail flashing.

He didnt run after her. No man can run down a deer. A panther maybe, or a wolf, or two wolves working in concert. He might have brought her down with a pistol but his pistol was lost in Louisville along with his boots. He cut a six-foot length of stout green cane and split one end of it and set the grip of his knife in the notch. With this rough blade-chucker in his right hand he went the way the doe had gone, following sign. She had not run far, and sometimes he could hear her light hooves crunching dry leaves of the ground cover. He heard the silence when she stopped and twice he made out the line of her shoulder and her head turned back, long ears revolving as she looked at him, but he never had a clear throw, with the undergrowthnot until she broke across the open road. Then he lunged forward, using every ounce of his breath and his heartbeat to whittle a few yards off of her lead as he whipped the green cane forward. The knife released as hed meant for it to and buried its blade behind her left shoulder.