Connor Towne ONeill - Down Along with That Devils Bones: A Reckoning with Monuments, Memory, and the Legacy of White Supremacy

Here you can read online Connor Towne ONeill - Down Along with That Devils Bones: A Reckoning with Monuments, Memory, and the Legacy of White Supremacy full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Algonquin Books, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Down Along with That Devils Bones: A Reckoning with Monuments, Memory, and the Legacy of White Supremacy

- Author:

- Publisher:Algonquin Books

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Down Along with That Devils Bones: A Reckoning with Monuments, Memory, and the Legacy of White Supremacy: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Down Along with That Devils Bones: A Reckoning with Monuments, Memory, and the Legacy of White Supremacy" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

We can no longer see ourselves as minor spectators or weary watchers of history after finishing this astonishing work of nonfiction. Kiese Laymon, author of Heavy

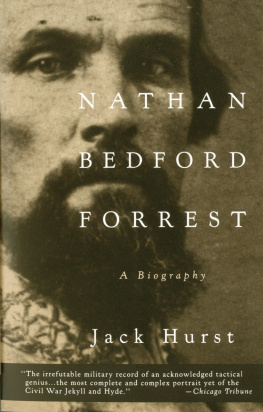

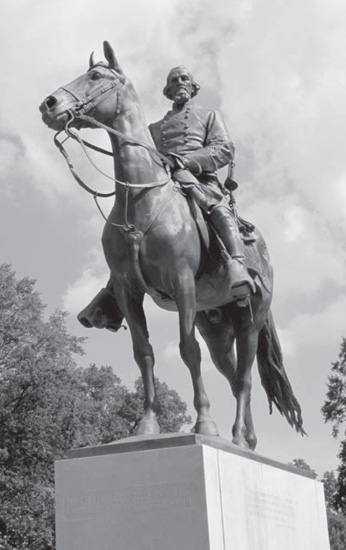

Connor Towne ONeills journey onto the battlefield of white supremacy began with a visit to Selma, Alabama, in 2015. There he had a chance encounter with a group of people preparing to erect a statue to celebrate the memory of Nathan Bedford Forrest, one of the most notorious Confederate generals, a man whom Union general William Tecumseh Sherman referred to as that devil. After that day in Selma, ONeill, a white Northerner transplanted to the South, decided to dig deeply into the history of Forrest and other monuments to him throughout the South, which, like Confederate monuments across America, have become flashpoints in the fight against racism.

Forrest was not just a brutal general, ONeill learned; he was a slave trader and the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. ONeill encountered citizens who still hold Forrest in cult-like awe, desperate to preserve what they call their heritage, and he also talked to others fighting to tear the monuments down. In doing so he discovered a direct line from Forrests ugly history straight to the heart of the battles raging today all across America. The fight over Forrest reveals a larger battle, one meant to sustain white supremacya system that props up all white people, not just those defending the monuments. With clear-eyed passion and honest introspection, ONeill takes readers on a journey to understand the many ways in which the Civil War, begun in 1860, has never ended.

A brilliant and provocative blend of history, reportage, and personal essay, Down Along with That Devils Bones presents an important and eye-opening account of how we got from Appomattox to Charlottesville, and of our vital need to confront our past in order to transcend it and move toward a more just society.

Connor Towne ONeill: author's other books

Who wrote Down Along with That Devils Bones: A Reckoning with Monuments, Memory, and the Legacy of White Supremacy? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.