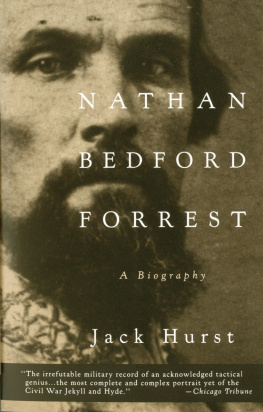

F IRST V INTAGE C IVIL W AR L IBRARY E DITION ,

M ARCH 1994

Copyright 1993 by Jack Hurst

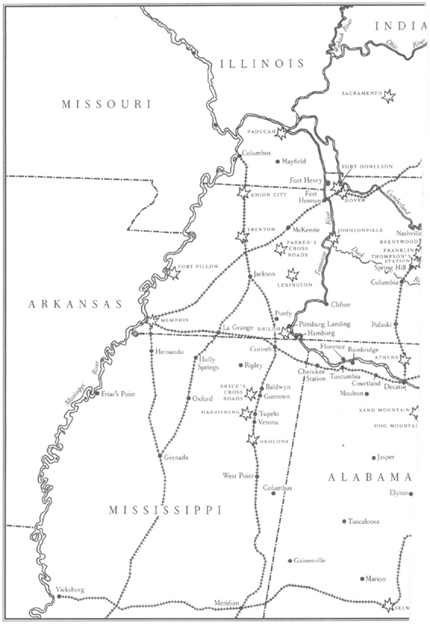

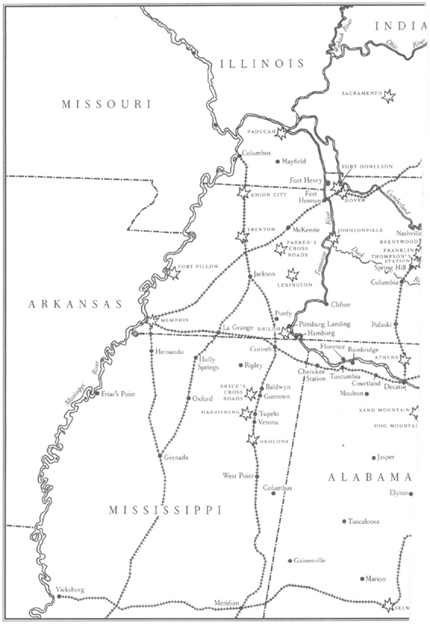

Maps copyright 1993 by William J. Clipson

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American

Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in

Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Originally published in hardcover by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.,

New York, in 1993.

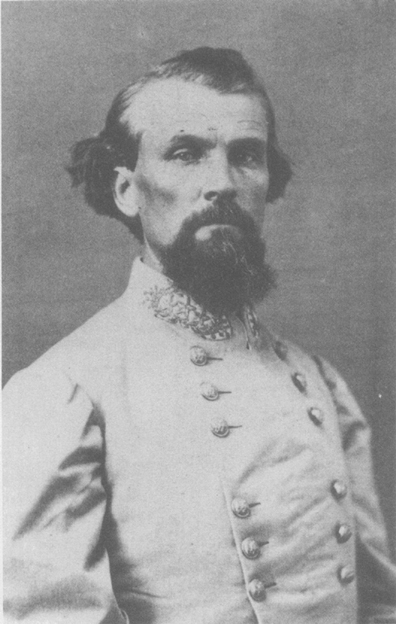

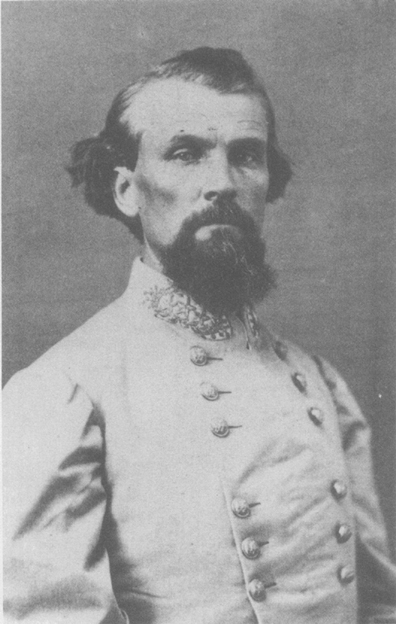

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the Massachusetts Commandery Military

Order of the Loyal Legion and the U.S. Army Military History Institute

for permission to reprint the frontispiece photograph.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hurst, Jack.

Nathan Bedford Forrest: a biography/by Jack Hurst.

Ist Vintage Civil War library ed.

p. cm.(Vintage Civil War library)

eISBN: 978-0-307-78914-3

1. Forrest, Nathan Bedford, 18211877. 2. GeneralsUnited StatesBiography.

3. Confederate States of America. ArmyBiography. I. Title. II. Series.

E467.1.F72H87 1994

973.73092dc20

[B] 93-42200

v3.1

To the memory of

Charles McKinley Hurst,

who in his much more diplomatic way

was a fighter too

C ONTENTS

Prologue

A DOZEN YEARS after the Civil War, the South overturned its outcome. Representatives of Ohio governor and former Union general Rutherford B. Hayes surrendered to former Confederates who had become United States senators and congressmen, and Hayess emissaries agreed to restore to the South the complete home rule Confederate armies had lost in the rebellion quelled in 1865. In return, Southerners provided the thin margin that defeated Democrat Samuel J. Tilden and elected Hayes president. Bending their conservative-Democratic principles, they certified questionable Republican ballots in Louisiana and South Carolina and handed those states to Hayes, thereby deciding a deadlocked race by a single electoral vote and averting a threatened resumption of formal hostilities. Once installed as the nations nineteenth chief executive, Hayes withdrew from Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida the last occupation troops of Reconstruction. The Confederate South was left free virtually to reenslave that third of its people whom Abraham Lincoln had declared emancipated in 1863.

The twelve-year struggle following Robert E. Lees surrender at Appomattox, Virginia, was in some ways as ugly as the four years of war had been: a guerrilla affair in which bands of unreconstructed rebels made night attacks in ghostly shrouds symbolizing the Confederate dead. Their methods, however, were anything but ghostly. Beating, whipping, and murdering, they drove from ballot boxes blacks and whites seekingsome sincerely, some otherwiseto further the fragile concept of racial equality. Before Hayess surrender, these night riders already had recaptured most of the old Confederacy piecemeal. The political power in Virginia and Tennessee had been reclaimed in 1869, North Carolina and Alabama the following year, Georgia the year after that, Texas in 1873, Arkansas in 1874, and Mississippi in 1875. The Hayes bargain, as it became known, returned the final three secession statesFlorida, Louisiana, and South Carolinato neo-Confederate control that would last most of another century.

While the ex-Confederates were anointing Hayes in Washington, the brief but pivotal leader of their clandestine war for Rebeldoms restoration was dying in Memphis, Tennessee. Impoverished, old before his time, his magnificent frame reduced to a gaunt shell of hardly a hundred pounds, fifty-five-year-old Nathan Bedford Forrestfiercest and arguably most brilliant icon in the Confederate military pantheonhad accepted at last the Christian faith of his familys women and begun to sound repentant. A fellow Confederate general who saw him during this twilight of his strength found the once-demonic warrior possessing the gentleness of expression, the voice and manner of a woman.

I am not the same man you knew, he told a former military aide who hadnt seen him in years.

Hardly. The man the former subordinate had known was the Souths storied Wizard of the Saddlean epic figure who, having risen from log cabin privation to wealth as an antebellum slave trader, became the only soldier South or North to join the military as a private and rise to the rank of lieutenant general. He was also the intrepid combatant who killed thirty Union soldiers hand to hand, had twenty-nine horses shot from beneath him, and was so feared by even his most warlike opponents that one of them, William T. Sherman himself, pronounced him a devil who should be hunted down and killed if it costs 10,000 lives and bankrupts the [national] treasury. Lee, Sherman, and other leaders on both sides ultimately were quoted as declaring him the most remarkable soldier the war produced.

A cavalryman, Forrest was little given to the foolhardiness common to mounted soldiers in his era. He often conserved manpower by using his force as a lightning infantry whose horses were employed to reach critical points at which to dismount and fight behind cover. Whether he was mounted or afoot, however, his aim always was ultimately offensive: to find the most advantageous positions from which to attackover and over, often from several directions at once. When the enemy turned to flee, he sometimes pursued for days, still attacking. Like the men of Stonewall Jackson, except more personally, Forrests soldiers feared him more than the enemy, and with good reason. Assaulting or shooting them with his own hands when they tried to run from battles, he compelled them to run in the opposite direction. His favorite military tactic was the charge, which he so trusted that he employed it even on a charging enemy rather than simply await assault.

Symbolizing his approach to life, the charge also was usually the best means of achieving one of his primary military goals. That goal, and his postwar description of it, became one of historys more renowned formulas for the successful conduct of warfare. His aim, he said, was to get to the critical position first with the most men. That, however, was merely prefatory to his overall objective. Whereas Sherman famously defined war simply as hell, Forrests definition of it was more specific, refining organized combat to its awful essence. War, he said, means fightin, and fightin means killin.

Albert T. Goodloe, meeting Forrest after the war aboard a steamboat, asked how he managed to win nearly all his battles despite almost invariably being severely outnumbered. The answer was that of a man who not only fought but thought. He said that most men regarded a battlefield with horror and consternation and that he therefore tried to make its initial appearance as shocking to the enemy as possibl[e], hurling his entire force against them in the fiercest and most warlike manner possible. He would thus overawe and demoralize at the very start and, with unabated fury, continue the demoralization by a constant repetition of blows killing, capturing, and driving them with but little difficulty.

Next page