Contents

Guide

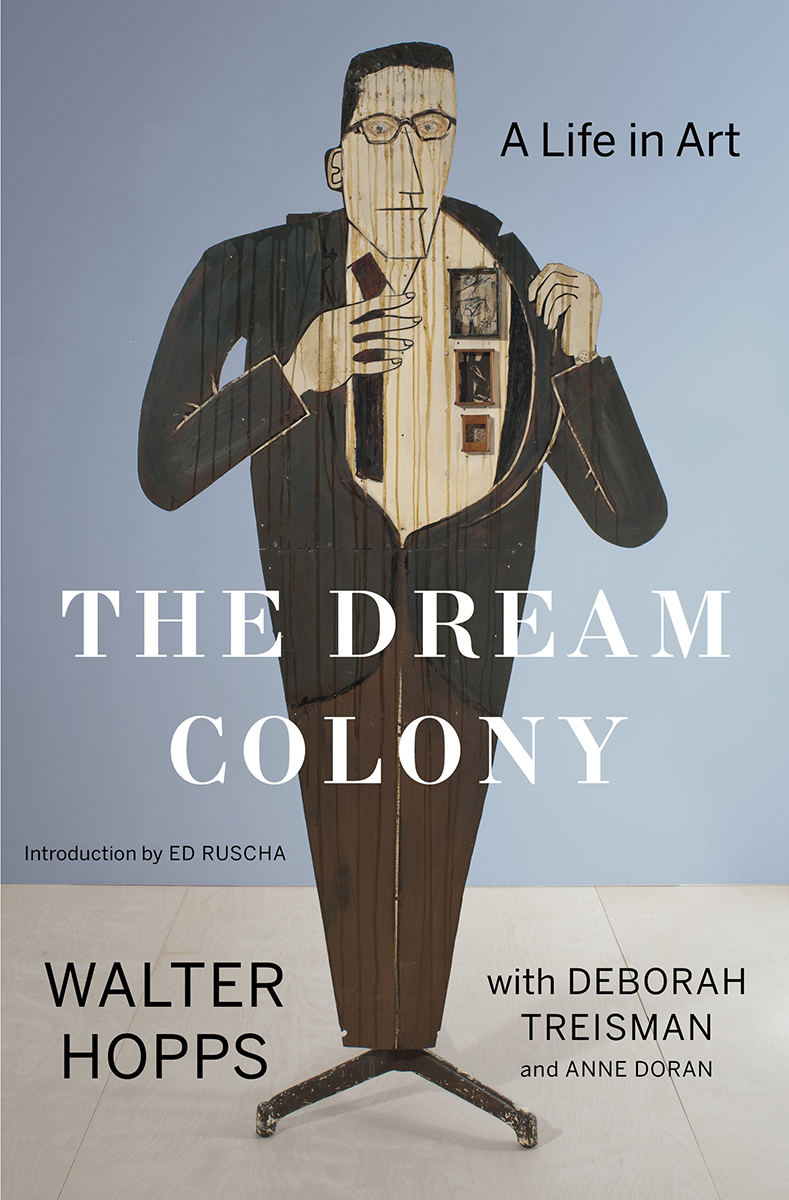

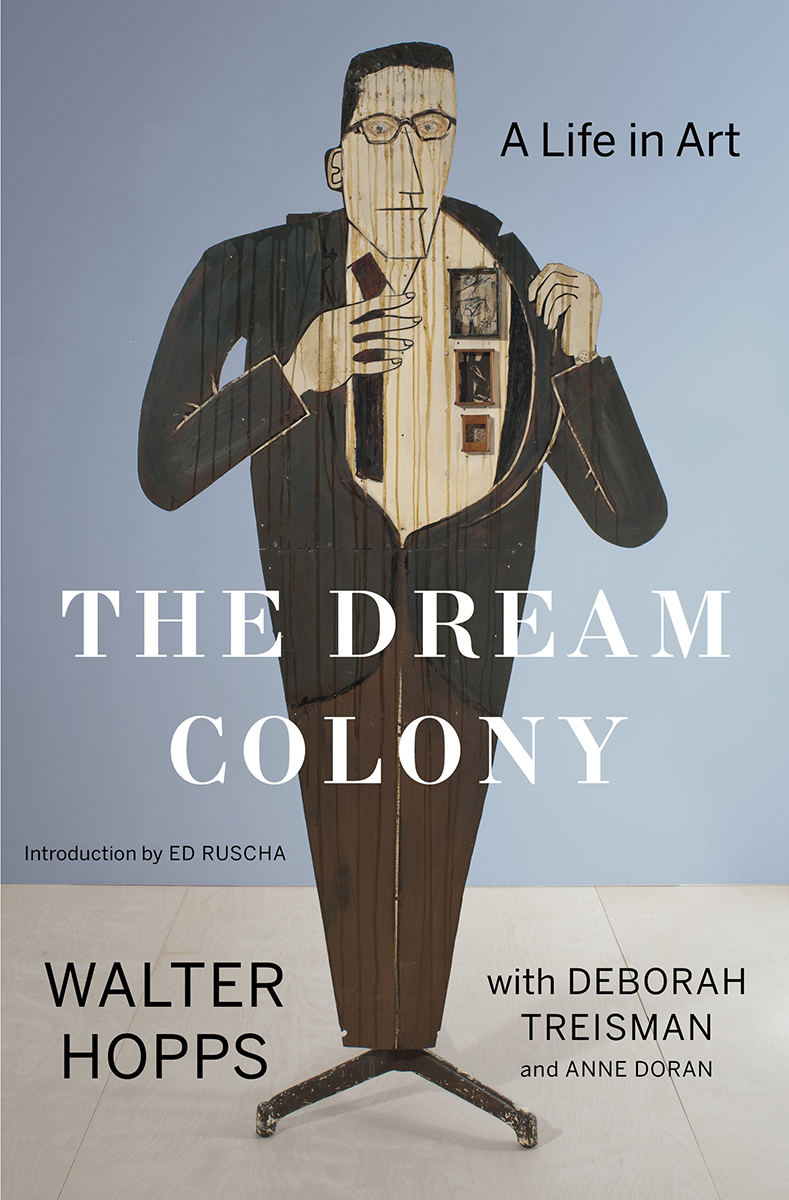

THE DREAM COLONY

To all the artists I have ever known, and to Caroline, the most magical one of all.

CONTENTS

I had my own secret world for many years. Still do. Calvin Tomkins once asked me how many artists I actually thought about. I said, You mean the living ones? Or the ones Im interested in? He said, Well, just in American art. And I said, Well, its near a thousand. And he said, What? And I said, Somewhere between eight hundred and a thousand. He said, Well, what do you mean think about? I said, If Ive looked at it, Im thinking about it. Havent you looked at that many artworks, visiting museums and galleries and so on? How can you help thinking about them?

Walter Hopps

As we walked slowly through the galleries, I remarked on the number of times I had been told that Hopps had the sensibility and the temperament of an artist. Had he ever thought of being an artist, I inquired, or was what he did close enough to that?

He pondered the question for a moment. I think of myself as being in a line of work that goes back about twenty-five thousand years, he said then. My job has been finding the cave and holding the torch. Somebody has to be around to hold the flaming branch, and make sure there are enough pigments. Ive been involved in what I consider getting this stuff made. Anyway, to answer your question, yes, Id say that what I do is quite close enough.

Calvin Tomkins, A Touch for the Now, The New Yorker , July 29, 1991

I met Walter Hopps for the first time in the winter of 1993. I was twenty-three and living in New York, and was applying to be the managing editor of Grand Street , the literary and art quarterly for which Hopps was the art editor. Having been told by Jean Stein, the editor and publisher of the magazine, that anyone she hired had to be approved by Walter first, I was nervous about my limited background in art. I didnt know much about Walter at the timeonly that he was the director of the Menil Collection, in Houston, and that hed had a renowned career as a curator of contemporary art. Walter called to arrange an interview and suggested that we meet at the Temple Bar on Lafayette Street. Thirty minutes after our scheduled time, he appeared in the Temple Bars dark, velvet-lined room, along with the artist (and Grand Street contributing editor) Anne Doran, carrying several folders of contact sheets. Were trying to put together a portfolio of photographs of graffiti memorials to dead gang members, he barked. Which of these pictures would you use? I sorted through the images as he watched. Right, he said. Now we just need to give this a damn title.

Two weeks after I started the job, in February, 1994, Walter suffered a brain aneurysm that left him hospitalized for a few months. (It was a testament to Walters tenacity that he came through it as rapidly as he did and made an almost unprecedented recovery.) In the days after an operation to repair the aneurysm, disoriented and suffering from short-term memory loss, Walter was convinced that it was 1963 and that he was in Pasadena, California, with a show to hang.

It was no coincidence that the strongest memory to surge up came from his time in Pasadena. It was as the director of the Pasadena Art Museum, in the mid-sixties, when still in his early thirties, that he established his reputation as one of the most innovative curators working in the United States. There, he was the first American museum curator to mount retrospectives of the works of Marcel Duchamp and Joseph Cornell and the first to honor Pop Art with an exhibition, before it was even known as Pop Art. But his involvement in the art world had begun much earlier. In his teens, as part of a group of gifted high-school students in Los Angeles, Hopps had been taken on a tour of the home of Walter and Louise Arensberg, the famous collectors of Dadaist and Surrealist art, and had been so startled and intrigued by what he saw there that he repeatedly skipped class to spend days at their house exploring and studying their collection. At age twenty, he opened his first gallery, Syndell Studio, in L.A. Five years later, he and the then unknown artist Edward Kienholz cofounded the Ferus Gallery, which would support the work of a new generation of groundbreaking artists, Andy Warhol, Ed Ruscha, Roy Lichtenstein, and Frank Stella among them.

In 1967, when the thirty-four-year-old Hopps became the director of Washingtons Corcoran Gallery of Art, the New York Times billed him as the most gifted museum man on the West Coast (and, in the field of contemporary art, possibly in the nation). A few years later he became the curator of twentieth-century American art at the Smithsonians National Collection of Fine Arts (NCFA), where he mounted a retrospective of Robert Rauschenbergs work and created the Joseph Cornell Study Center. In 1980, Hopps began working with Dominique de Menil to create the Menil Collection in Houston. In de Menil, he found a patron and a colleague who was willing to lend full support to his unorthodox approach and work habits.

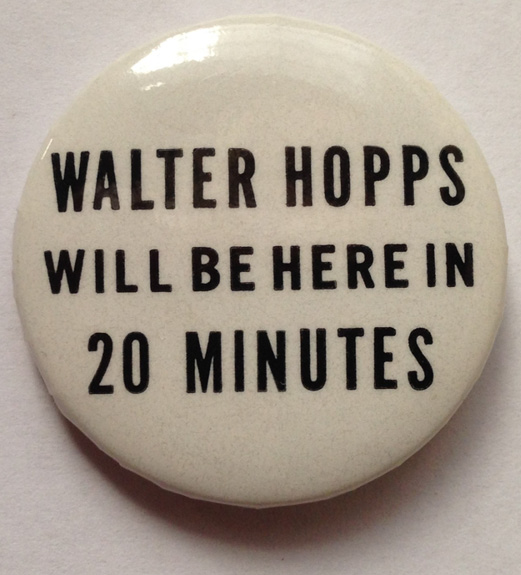

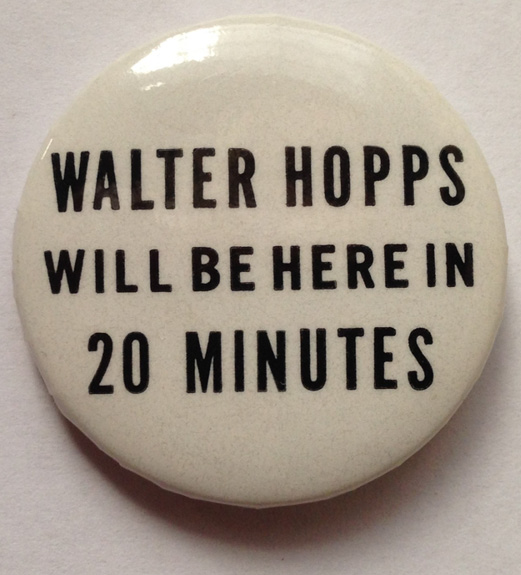

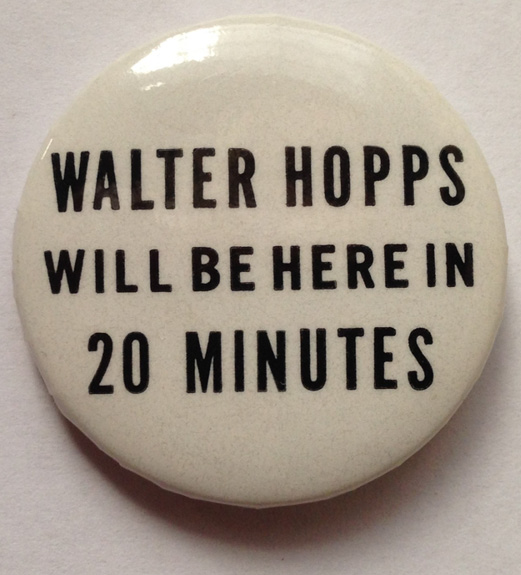

For much of his working life before Houston, Walter was chronically latehis staff at the Corcoran actually had buttons made that said WALTER HOPPS WILL BE HERE IN 20 MINUTES and he sometimes went missing for days at a time, only to return and work straight through the night hanging a show. (If I could find him, Id fire him, Joshua Taylor, his boss at the NCFA, used to say.) In 1978, Hopps staged Thirty-Six Hours at the Museum of Temporary Art, in D.C.a show in which he hung every art work that was brought to him over the course of a day and a half. Erratic in his schedule, he was never erratic in his commitment to the art he loved. In his two and a half decades in Houston, he continued to discover, befriend, and champion the work of young artists. In the years before he died, in 2005, at age seventy-two, he was responsible for major retrospectives of the work of Edward Kienholz (at the Whitney Museum), Robert Rauschenberg, and James Rosenquist (both at the Guggenheim Museum).

Button created by the staff of the Corcoran Gallery, c. 1970. Photograph by Caroline Huber.

Unrelenting independence and nonconformism marked Walters life as well as his curatorial and critical mind. The late Anne dHarnoncourt, then the director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, claimed that his success came from his sense of the character of works of art, and of how to bring that character outwithout getting in the way. Hans-Ulrich Obrist, in a 1996 Artforum article, called him both consummate insider and quintessential outsider. Or, as the writer Calvin Tomkins explained it in The New Yorker in 1991, In a Hopps exhibition, considerations of art history and scholarship are often present, along with ideas about style and influence and social issues, but the primary emphasis is always on how the art looks on the wall, and this, surprisingly, makes Walter Hopps something of a maverick in his profession.

Walters maverick qualities made him one of the most influential figures in mid to late twentieth-century American art. What makes him live in the minds of those who knew him are his forthrightness, his eccentricity, his imaginationand his storytelling. Over decades at the forefront of American creativity, he accumulated a store of anecdotes, scenes, ideas, and insights that could have filled several books. He was a riveting, funny, and discerning narrator. As Paul Richard recalled, in the Washington Post , His speech was like a Jackson Pollock drip painting, swooping, swelling, doubling back. He mesmerized. He taught. The stories Walter had to tell were not academic or critical, as such, although his thinking incorporated both scholarship and history; rather, they were vivid, personal, surprising, irreverent, and enlighteningan extremely privileged view into some of the greatest artistic minds of the century.