Contents

Guide

When Mortals Play God

When Mortals Play God

Eugenics and One Familys Story of Tragedy, Loss, and Perseverance

John Erickson

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

86-90 Paul Street, London EC2A 4NE

Copyright 2022 by John Erickson

All rights reserved . No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Is Available

ISBN: 978-1-5381-6669-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN: 978-1-5381-6670-3 (electronic)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

For Millie

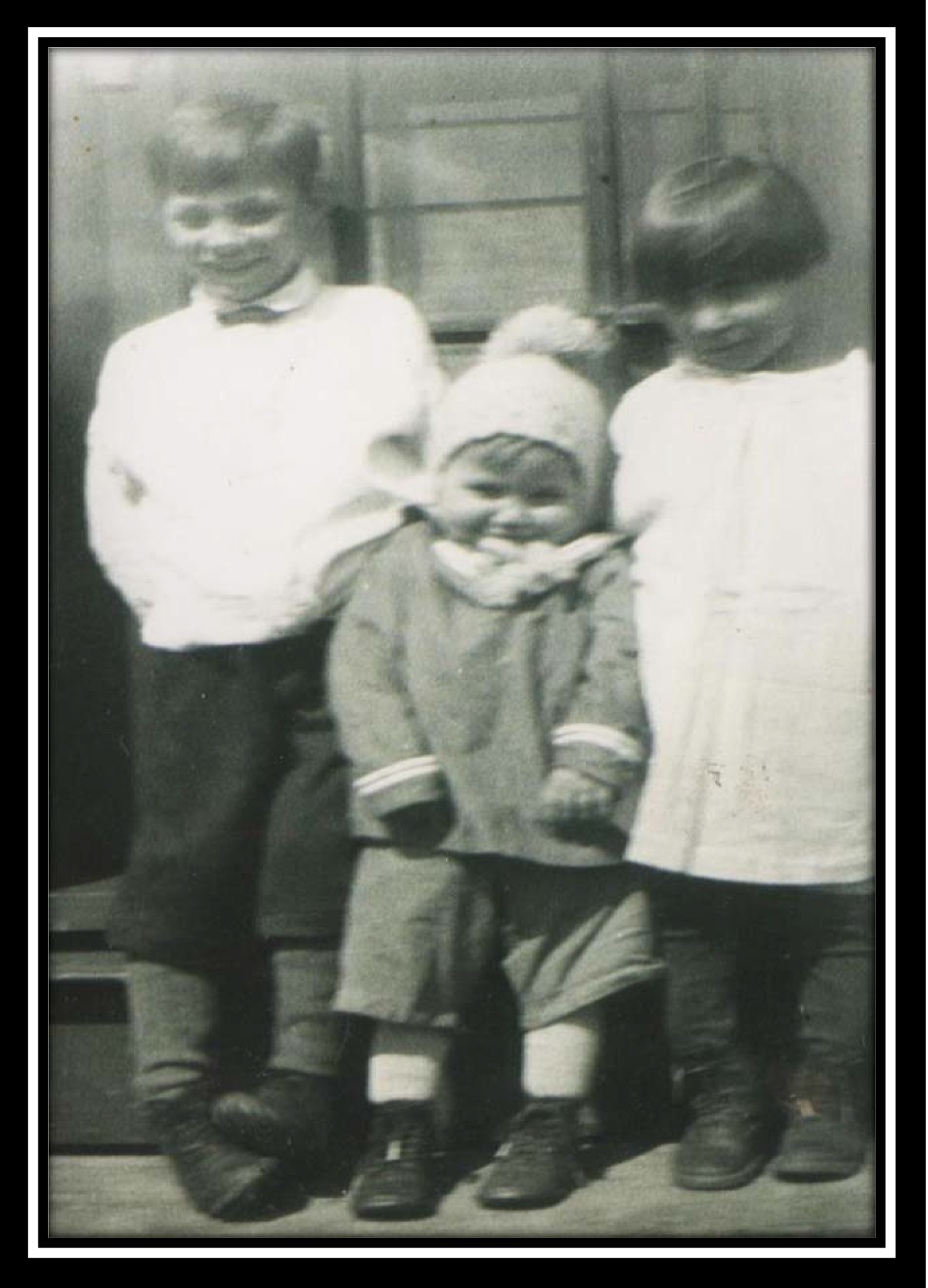

I first came across John Ericksons grandmother Rose in a large red and gold leather-bound volume with the words sterilization cases embossed on the cover. I was doing research on eugenic sterilization at the Minnesota History Center, and she was listed, along with a thousand others, in a register of sterilization operations performed at the state institution for the feebleminded in southern Minnesota. Rose was one of seven women to undergo surgery one Friday in April 1926, a few months after the states sterilization law went into effect.

I tried to tell the stories of women like Rose in my 2017 book, Fixing the Poor: Eugenic Sterilization in the Twentieth Century , but after years of research I could tell only a partial story about sterilization at one point, possibly the lowest point, in peoples lives. In When Mortals Play God , John Erickson rounds out the story. His vivid portrait of Rose and her family over generations is a powerful expos of the heartbreakingand long-lastingeffects of an epic policy failure.

Roses story may seem shocking today, but it was all too common in 1920s and 1930s America. Thirty-two states passed eugenic sterilization laws between 1907 and 1937. More than 63,000 Americans were sterilized. Minnesota alone sterilized at least 2,350 persons, nearly two-thirds of them women like Rose who carried the label feebleminded.

The sterilization crusade swept other countries too. Sweden, Norway, Canada, Japan, and of course Nazi Germany, which sterilized an estimated 400,000 people, were among the nations with eugenics laws designed to prevent the reproduction of the unfit: the so-called mentally defective, insane, criminalistic, epileptic, or morally degenerate. In 1927 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that compulsory sterilization for eugenic purposes was constitutional. Its notorious decision, Buck v. Bell , cemented the states power to prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind and authorized the involuntary sterilization of Carrie Buck, a young white woman from Virginia who was branded feebleminded and promiscuous because she was poor and had a baby out of wedlock. And coerced sterilizations persisted long after eugenics ideas were discredited, as recent scandals over forced sterilizations in womens prisons and immigrant detention centers makes clear.

Eugenics, a term the English statistician Francis Galton coined in 1883 from the Greek word for well-born, was the science of improving the human race through better breeding. Eugenics became popular because it combined the commonsense idea that certain attributes run in families with a scientific (but simplistic) theory of human heredity. Eugenicists posited that personal characteristics like intelligence, criminality, alcoholism, and immorality were biological traits transmitted across generations in a predictable pattern. Just as farmers could improve their livestock through animal breeding, they believed that poverty, crime, and disease could be reduced if people with desirable traits had more children and those with undesirable traits had fewer. Eugenicists wanted the fittest families to have more children, but eugenics legislation focused chiefly on ridding society of supposed undesirables. As a result, the least powerful segments of the populationAfrican Americans, indigenous people, immigrants, people with disabilities, and individuals like Rose who were poor, uneducated, and oversexedwere disproportionately targeted.

Eugenics is most closely identified with sterilization, but it also involved prohibitions on interracial marriage and the marriage of disabled people, drastic reductions to immigration on racial grounds, andof particular importance to Roses familythe compulsory institutionalization, or eugenic segregation of those deemed to be feebleminded. The early twentieth century brought a major expansion of custodial state institutions, with many states mandating the compulsory institutionalization of the feebleminded during their childbearing years. When Rose was committed to the Minnesota School for the Feeble-Minded in 1924, more than 43,000 people across the United States were similarly confined. For many, sterilization was the price they had to pay to regain their freedom.

If eugenics ideas justified state-mandated sterilizations, in practice, sterilization programs functioned to reduce welfare costs by ensuring that poor, sexually active women did not have more children than they could care for or support. Roses entire family fell victim to that system: child welfare authorities entered her house, put her in an institution, took away her children, and convinced her mother to consent to her daughters sterilization. While Roses family struggled to cope with hardship, calamity, and loss, welfare officials protected her children by removing them from their home. The family never saw her youngest son again.

Rose came of age in the flapper era, when young women defied traditional expectations for feminine behavior and asserted their sexual independence. Her story illuminates the cost of that defiance. As a teenager during World War I, Rose drank and socialized with older men. She was eighteen when her first husband deserted her and their infant son, twenty-one when her second husband left her with two young children, and twenty-three when her third child was born. She was sterilized at twenty-four. To state and county welfare authorities, Roses sexual immorality was a symptom of her feeblemindedness and the cause of her broken home. John shows that there was more to the story. What social workers saw as inherited degeneracy we recognize today as the intergenerational consequences of trauma, loss, hunger, and sexual abuse. A kinder child welfare system might have helped Roses family stay together. Instead, the family was torn apart. The consequences echo today for the DeChaines as for many others.

Since surgical sterilization prevents reproduction, its impact is often assumed to have ended in one generation. But many sterilized individuals, like Rose, already had children, and they too suffered from the states eugenics policies.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.