an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

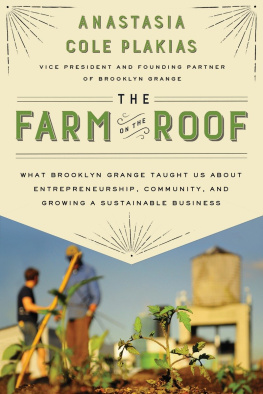

Copyright 2016 by Brooklyn Grange, LLC

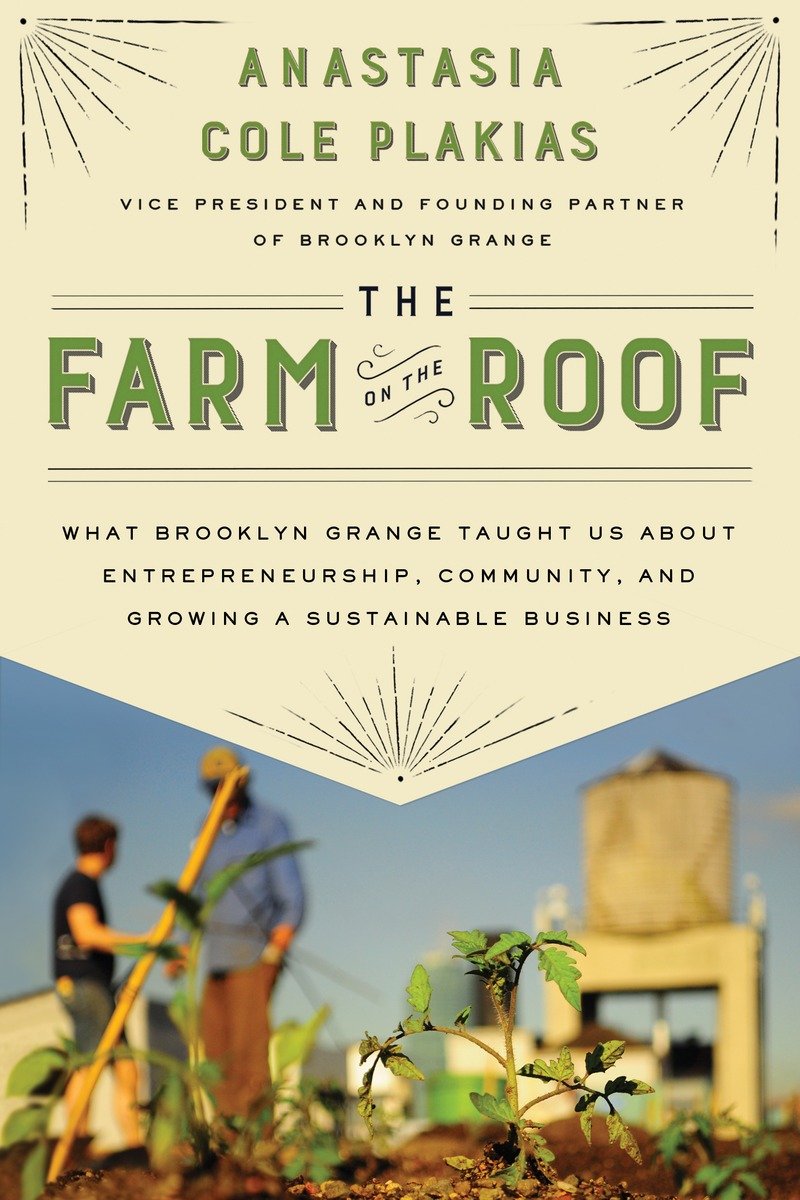

Unless otherwise specified, all photographs are provided courtesy of Brooklyn Grange, LLC.

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Most Avery books are available at special quantity discounts for bulk purchase for sales promotions, premiums, fund-raising, and educational needs. Special books or book excerpts also can be created to fit specific needs. For details, write SpecialMarkets@penguinrandomhouse.com.

eBook ISBN: 9780698404113

Version_1

To our amazing farmily who gave us a hand along the way. To the moms and dads who believed in us; the friends who listened and helped us solve problems; the investors, lenders, and Kickstarter supporters who put their money where their mouths were; the neighborhood green thumbs; the experienced farmers who picked up our calls; the girlfriends and boyfriends who cooked us dinners when we came home late; the husbands and wives who took an extra morning shift so we could get to work early; the journalists who helped us spread the word; the lawyers who gave us free advice; the coffee shops that gave us free Wi-Fi... There are too many to mention everyone by name, but we can never give thanks enough to the folks whove shown up in blasting heat and howling winds to make sure Brooklyn Grange thrives: Hester, Rob, Michael, Melissa, Michele, Matt, Bradley, Alia, Robyn, Cashen, and Tori, we love you.

CONTENTS

Introduction

NOWHERE TO GO BUT UP

A s 2008 rolled in, New York City was riding high: the economy was up, the crime rate was down, and something in the air made it feel like the greatest city in the world, at the greatest time in its history. The seedy Times Square of yesteryear had turned into Disneyland. Once-blighted areas of Brooklyn were reinventing themselves as meccas of creativity. Sidewalk cafs were teeming with urban sophisticates drinking three-dollar lattes. Tourists streamed in and out of attractions, buying tchotchkes from street vendors. Some complained that this town wasnt gritty enough, but nobody seemed to mind that they could take the subway home late at night without fearing for their safety, iPhone earbuds tucked blithely into their ears.

Then in September of that year, everything fell apart: the subprime mortgage crisis, banking bust, and auto industry implosion triggered an economic downturn that had newspaper headlines warning of the next great depression. As the largest regional economy in the United States, New York City took the hit, hard. Sure, it could have been worse. New York wasnt Detroit, and the city remained relatively prosperous. But the shift was palpable. Suddenly the spirit of consumption that had defined the prior decade seemed embarrassingly ostentatious.

On TV screens across the country, a woman named Sarah Palin warned Main Street about the corporate cronyism of Wall Street. Meanwhile, a Black man was running for president on a platform of change and making young voters believe it was something they had the power to effect. The nation was at a crossroads: On the one hand, our sense of security had been dashed and everything we thought we knew about being the most powerful country in the world was revealed to be the long con of a powerful few. On the other hand, as this reality dawned, it brought with it the prospect of a new day. As voters streamed into polling precincts at the highest rates in forty years, one thing became clear: the country believed in hope.

This was the climate in which wemyself and a handful of other scrappy young Brooklynitesfirst came together to start Brooklyn Grange, the worlds first commercial rooftop farm. Each of us left behind promising careers during the worst recession in decades to do something about which we were totally uncertain. It wasnt that we had doubts about urban farmingurban farms had existed long before we decided to start one. And while no one had ever practiced rooftop farming at the scale we set out to, humans had succeeded in growing plants on roofs since the fabled hanging gardens of Babylon. But we set out to do it differently. We didnt simply want to farm; we intended to create a small farm businessa self-sustaining enterprise that, like any other business, would have to turn a profit to survive. In an industry as fickle, susceptible, and lean as farmingand in an economic climate as competitive as the one in which we found ourselvessuccess was not a given.

If youre thinking that we started this endeavor because we saw an easy path to success, think again. Even though were now thriving, we will never be millionaires doing what we do, nor will we ever spend our summers on a shady porch sipping lemonade. Running our farm the way we do was important for other reasons. Led by our entrepreneurial head farmer and president, Ben Flanner, myself, and my partner Gwen Schantz, along with the owners of Robertas, a Brooklyn pizzeria, and later joined by our partner Chase Emmons, we were determined to operate a for-profit enterprise growing vegetables on a roof because we wanted to prove it was a worthwhile endeavor. By operating it as a for-profit enterprise, we set out to show the wider world that urban farming can be both an agriculturally and fiscally sustainable operationan industry that, if invested in, could help change the landscape of cities.

We also knew there was a long list of very good reasons that no one had ever done this before. Agriculture requires a certain scale to be profitable, and land in cities is scarce and expensive. And while rooftop space is less valuable than ground-level real estate, the cost of building it out is higher. Whats more, we were determined to be a truly sustainable business, focused not just on numbers but on what is known as the triple bottom line. Business authority John Eklington developed the triple-bottom-line framework to describe a business that accounts for its performance across three categories known as the Three Ps: people, planet, and profit. If a corporation generates revenues by pillaging an ecosystem of its resources, it is deriving profits at the expense of the planet. If another business manages to make a profit without wreaking ecological damage but must lay off an entire community of workers in order to do so, its benefits to the planet are coming at the cost of the people who inhabit it. The idea is to derive revenues while also generating natural and human capital: everybody wins.