Published in 2020 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016

Copyright 2020 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

First Edition

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior permission of the copyright owner. Request for permission should be addressed to Permissions, Cavendish Square Publishing, 243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016. Tel (877) 980-4450; fax (877) 980-4454.

Website: cavendishsq.com

This publication represents the opinions and views of the author based on his or her personal experience, knowledge, and research. The information in this book serves as a general guide only. The author and publisher have used their best efforts in preparing this book and disclaim liability rising directly or indirectly from the use and application of this book.

All websites were available and accurate when this book was sent to press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Jones, Naomi E.

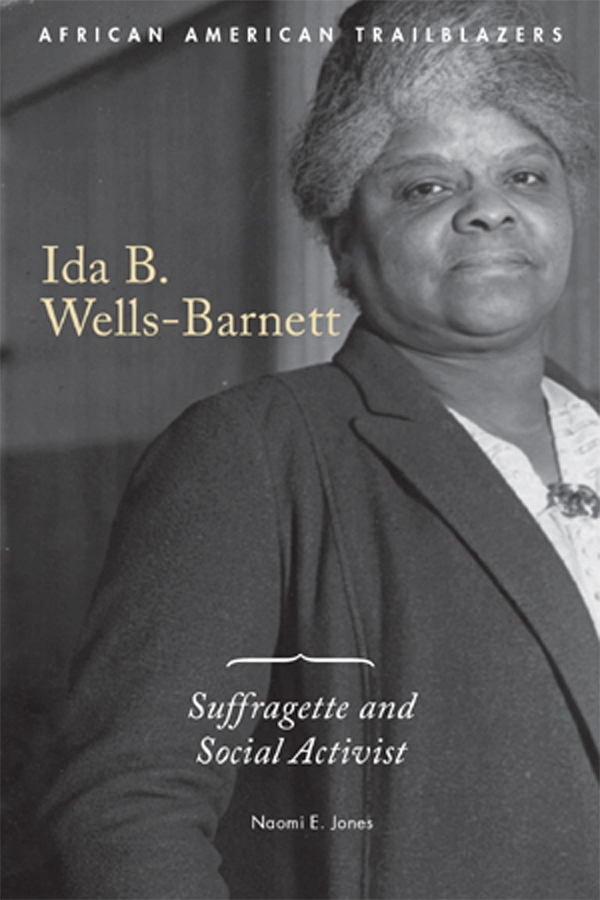

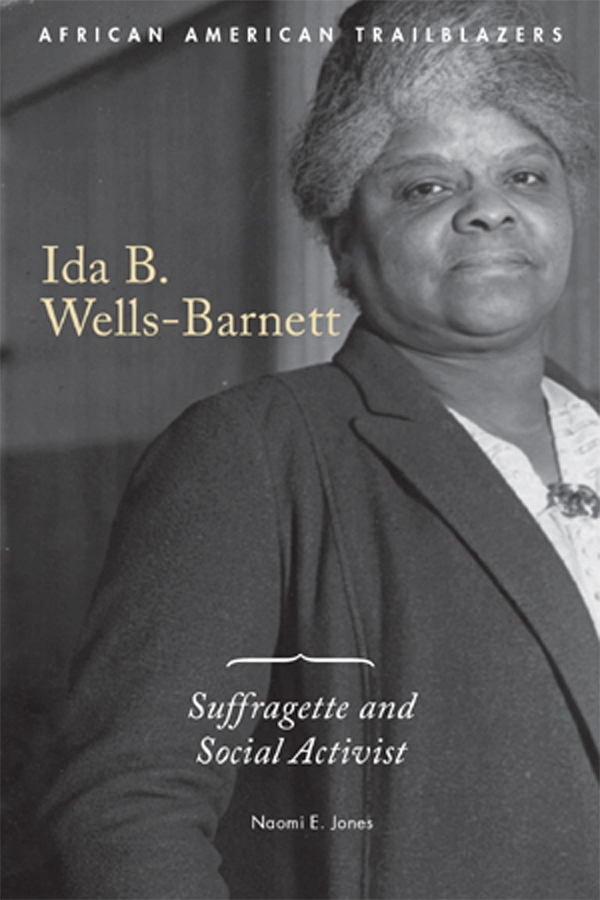

Title: Ida B. Wells-Barnett : suffragette and social activist / Naomi E. Jones.

Description: New York : Cavendish Square, [2020] | Series: African American trailblazers |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018047438 (print) | LCCN 2018047929 (ebook) | ISBN 9781502645623 (ebook) |

ISBN 9781502645616 (library bound) | ISBN 9781502645609 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Wells-Barnett, Ida B., 1862-1931--Juvenile literature. | African American women civil rights workers--Biography--Juvenile literature. | Civil rights workers--United States--Biography--Juvenile literature. | Journalists--United States--Biography--Juvenile literature. | Suffragists--United States--Biography--Juvenile literature. | African Americans--Civil rights--History--Juvenile literature. | Lynching--United States--History--Juvenile literature. | United States--Race relations--Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC E185.97.W55 (ebook) | LCC E185.97.W55 J66 2020 (print) | DDC 323.092 [B] --dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018047438

Editorial Director: David McNamara

Editor: Kristen Susienka

Copy Editor: Alex Tessman

Associate Art Director: Alan Sliwinski

Designer: Joseph Parenteau

Production Coordinator: Karol Szymczuk

Photo Research: J8 Media

The photographs in this book are used by permission and through the courtesy of: Cover, Chicago History Museum/Archive Photos/ Getty Images; pp. TonyTheTiger, Own work/File: 20070601 Wells House edit. jpg/Wikimedia Commons/CCA-SA 3.0 Unported; pp. 100-101 Adam Robison/The Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal AP Images.

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

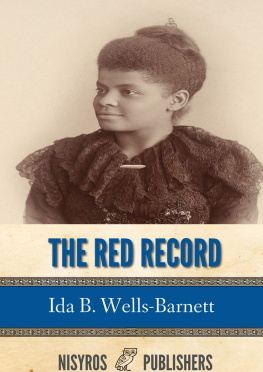

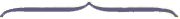

This portrait shows Ida B. Wells-Barnett as a young woman in 1893.

INTRODUCTION

The Princess of the Press

I da B. Wells-Barnett grew up during the beginning of the Reconstruction period that followed the Civil War. This was a time of hope for newly freed slaves. As a child, Wells-Barnett saw her father vote for the first time, black men elected to government positions, educational opportunities for African Americans, and the passing of laws that forbade discrimination. However, before long she learned that racial violence would replace slavery, in the form of lynching.

Career and Opportunities

Wells-Barnett would have many professional opportunities throughout her life. She began a career at sixteen as a teacher. Several events later would influence her transition into a lecturer, investigative journalist, and social justice advocate. Her lawsuit in 1884 against the Chesapeake, Ohio, and Southwestern Railroad for assault and discrimination led to the beginning of her journalist career. Wells-Barnett sent her first essay to a local newspaper in 1884, and within five years she had become the first woman owner and editor of a black newspaper in American history. Nicknamed the Princess of the Press, she used her journalism career to fight prejudice and injustice through her writings, speeches, and protests. She fought lynching and worked to solve social issues such as poverty, poor housing, and inadequate schools.

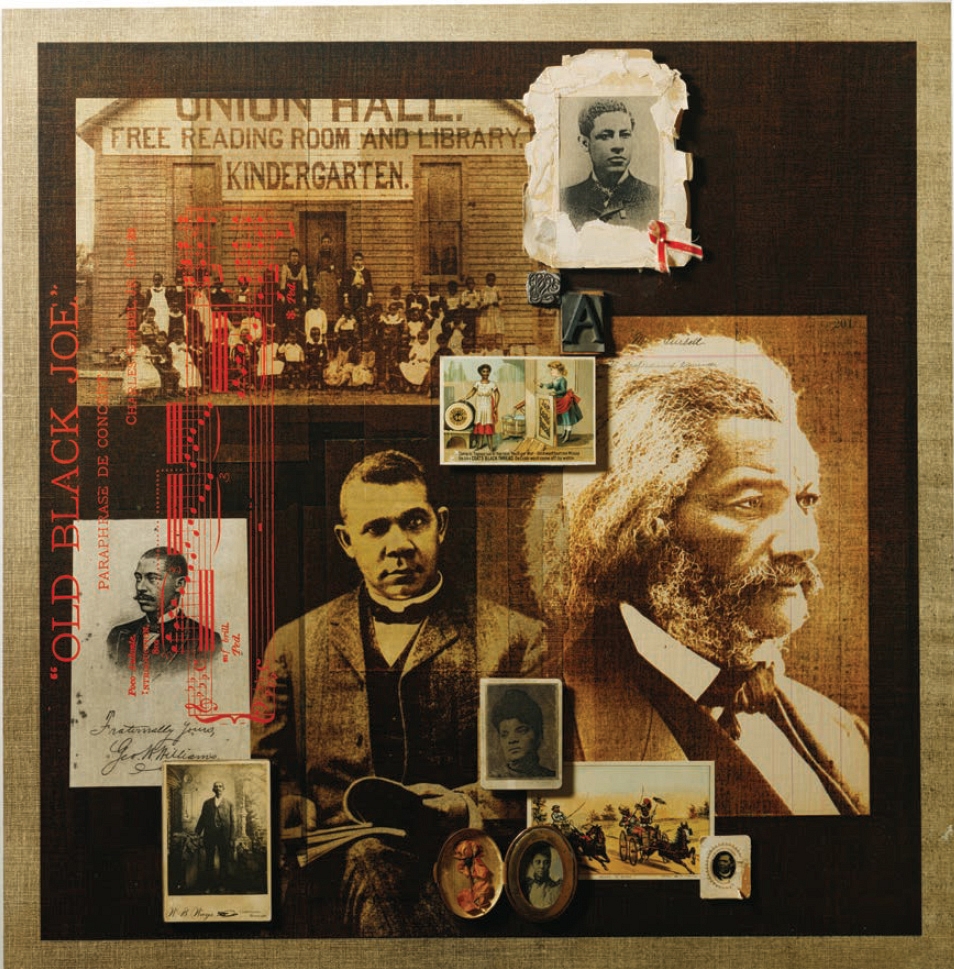

Wells-Barnett met and befriended Frederick Douglass in 1892. They shared many goals, and he wrote letters of support for her and mentored her. She also worked with other civil rights leaders, including W. E. B. Du Bois. Although she helped many clubs and organizations that worked toward suffrage, civil rights, and urban reform, she never became a long-term member of any of them. Known for being blunt and outspoken, Wells-Barnett often ran into conflict with her fellow activists.

Spreading the Word

In the 1890s, she traveled across the East Coast and Great Britain giving talks on the racial injustices happening throughout the United States. Female lecturers were rare back then, but women were becoming increasingly active in reform movements, womens clubs, and fighting for suffrage.

After moving to Chicago, Wells-Barnett shifted her focus to womens suffrage and encouraged more women of color to get involved in politics and the suffrage movement. She had a great deal of faith in the power of voting, and before women could vote, she worked to persuade men to vote for candidates who would fight lynching. She also urged women to vote once suffrage had been achieved.

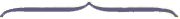

This collage of photographs features several famous African American leaders, including Ida B. Wells-Barnett (bottom center), Booker T. Washington (left center), and Frederick Douglass (right).

Toward the end of her life, Wells-Barnett became one of the first African American women to run for public office in the United States, and the first female African American political activist to write an autobiography. Her contributions to civil rights would influence later twentieth-century activism.

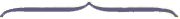

This illustration depicts Robert E. Lee (center left, seated) surrendering to Ulysses S. Grant (center right, seated) at the end of the Civil War.

CHAPTER ONE

Fighting for Equal Rights

T he period known as Reconstruction began at the end of the Civil War. It lasted from 1865 to 1877. For a while, the newly freed slaves were able to attend school, hold public office, sit on juries, own businesses, and freely go into any public place. Many Northern reformers traveled south to assist the freedmen by providing them with food, assistance in integrating into society, and education. However, many of their newly acquired rights were taken away by the end of 1885. As violence, segregation, and disenfranchisement spread, African Americans were systematically denied the right to vote and condemned to second-class status.