Latin cross festooned with daffodils and roses. Side panels are decorated in sunflowers and primroses representing a devotion to God and eternal love. Tomb of Edward J. Schinkel

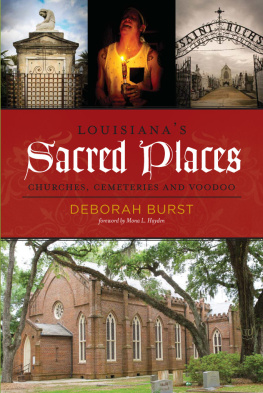

White marble weeping angel; tomb of Chapman H. Hyams, designed by architect Charles L. Lawhon and made by the Albert Weiblen Marble and Granite Company in 1915, Metairie Cemetery. Photograph by Jan White Brantley

Photograph by Jan White Brantley

To my grandparents Oliver & Annie Shipman and my parents, Ben & Martha Shipman Brantley,

thanks for teaching me that true strength, power, wisdom, and vision come from inside and culminate in love and gentleness.

To the love of my life, Jan White Brantley,

who knew my soul better than any other and who allowed me to share hers, and who taught me the simplicity and gentleness of true love and happiness.

The Truth in Art and Beauty is in the Love and Pain they Conceal.

Published by

Princeton Architectural Press

202 Warren Street, Hudson, NY 12534

Visit our website at www.papress.com

2019 Robert S. Brantley

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews.

Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions.

Editor: Sara Stemen

Designer: Paula Baver

Symbolic interpretation: Heather Veneziano, Cultural Heritage Advisor, Gambrel & Peak LLC

Special thanks to: Janet Behning, Abby Bussel, Jan Cigliano Hartman, Susan Hershberg, Kristen Hewitt, Stephanie Holstein, Lia Hunt, Valerie Kamen, Jennifer Lippert, Sara McKay, Parker Menzimer, Wes Seeley, Rob Shaeffer, Jessica Tackett, Marisa Tesoro, Paul Wagner, and Joseph Weston of Princeton Architectural Press

Kevin C. Lippert, publisher

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Brantley, Robert S., author. | Starr, S. Frederick, writer of foreword.

Title: Sacred ground : New Orleans cemeteries / Robert S. Brantley; Introduction by S. Frederick Starr.

Other titles: New Orleans cemeteries

Description: First edition. | New York : Princeton Architectural Press, [2018] Identifiers: LCCN 2018055158 | ISBN 9781616898212 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781616898779 (epub, mobi)

Subjects: LCSH: CemeteriesLouisianaNew Orleans. | CemeteriesLouisianaPictorial works. | New Orleans (La.)Biography.

Classification: LCC F379.N562 A224 2018 | DDC 363.7/50976335dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018055158

Contents

S. Frederick Starr

Birds-eye view of St. Louis Cemetery #1

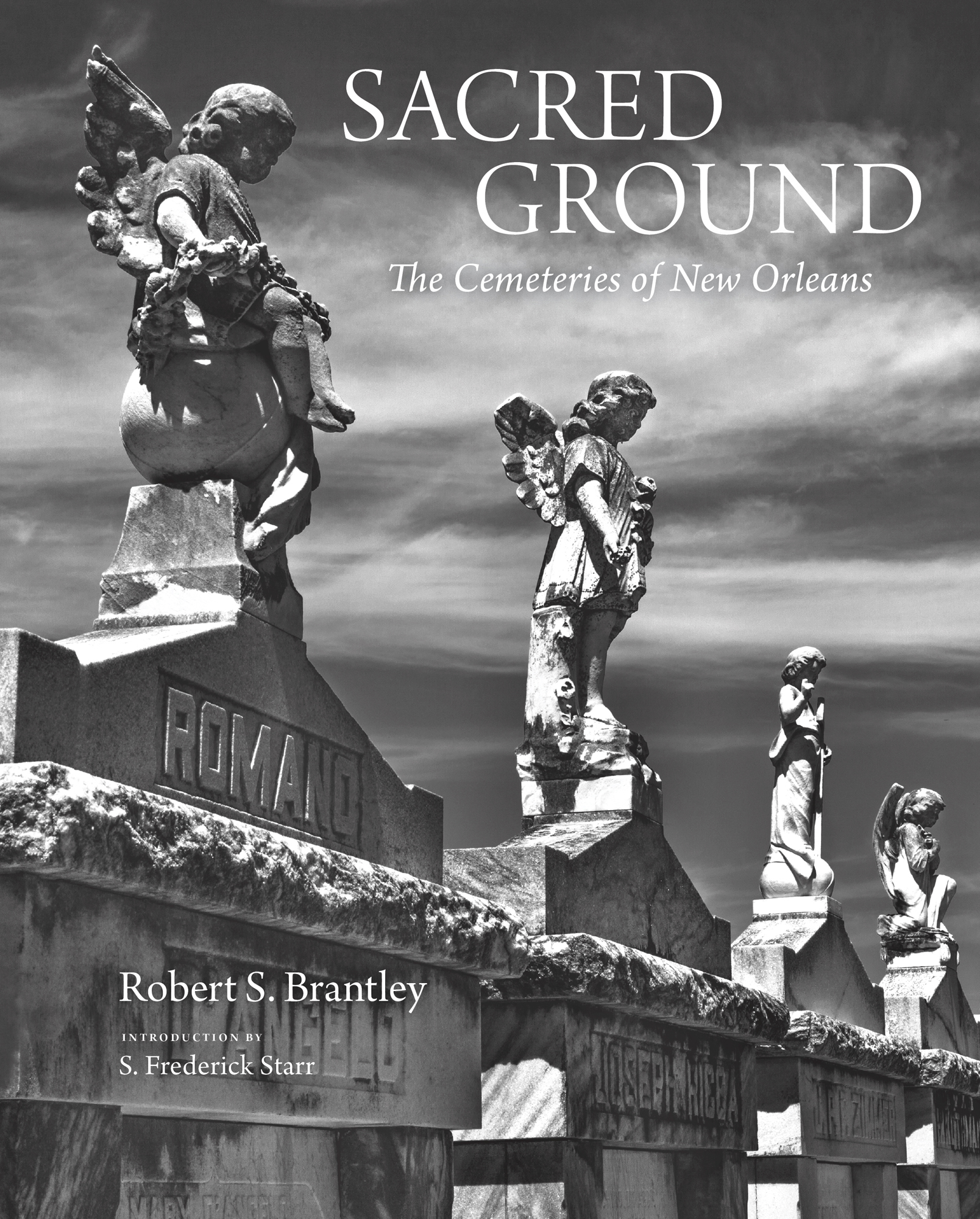

Sacred Ground: The Cemeteries of New Orleans

S. Frederick Starr

Benjamin Henry Latrobe had designed the US Capitol and was thoroughly conversant with European architecture and design. Yet when he found himself, in 1804, strolling through New Orleanss St. Louis Cemetery, he confessed that he was perplexed and astonished by the place, that its design and tombs were like nothing he had seen before. Little did he suspect that he himself would be buried there.

Writers have tried to summarize the essence of New Orleanss fifty-nine cemeteries in such clichs as Cities of the Dead, which grow ever more trite over the years. Maybe that essence cannot be captured in words. Hats off, then, to master photographer Robert S. Brantley, who has endeavored to capture the essence of New Orleanss cemeteries in subtle photographic images. These pictures enable the thoughtful reader to ponder the subject and to consider New Orleanss funereal monuments as reflections of our eternal quest for permanence in an impermanent world.

In some respects New Orleanss cemeteries are indistinguishable from their counterparts in Boston, Baltimore, or Cincinnati. Their distinctiveness is real, however, and can be traced to four factors, three natural and one human. The first of these is the best known, namely, the citys high water table. With water lurking just under the grounds surface, it is impossible to bury the dead. Yet the Gospel according to John (19:3942) admonishes Christians to wrap the dead in linen and bury them, as was done with Christ himself. The only recourse was to lay down a brick foundation and place the corpse on a low floor, to which was then added simple sides and a roof. The corpse was still subject to the regions humidity and fierce summer heat, its quick decay reminding everyone of just how fragile is the flesh.

A second determining natural factor concerns the geology of the Lower Mississippi, which left the region with rich soil from the Midwest but no building stone or clays that could be transformed into hard bricks. Tombs had to be constructed of soft local bricks, which were then plastered and painted to imitate stone. Only a few of the rich could afford to clad their tombs with thin marble.

The third factor that defined New Orleans cemeteries was the prevalence until the early twentieth century of epidemics of cholera and yellow fever. Having chosen to live close by their neighbors, and with no understanding of the causes of the pestilences, the citizens of New Orleans died by the thousands in epidemics that recurred nearly every decade down to the last century. In one month alone, during the cholera epidemic of 1832, more than one thousand died, with their corpses piled up outside the citys main cemetery. Priests pronounced the last rites while standing by the mounds of bodies. True, the Mortuary Chapel, now Our Lady of Guadalupe, had just been completed on Rampart Street, but even without pews, it could not accommodate the crowds of mourners.

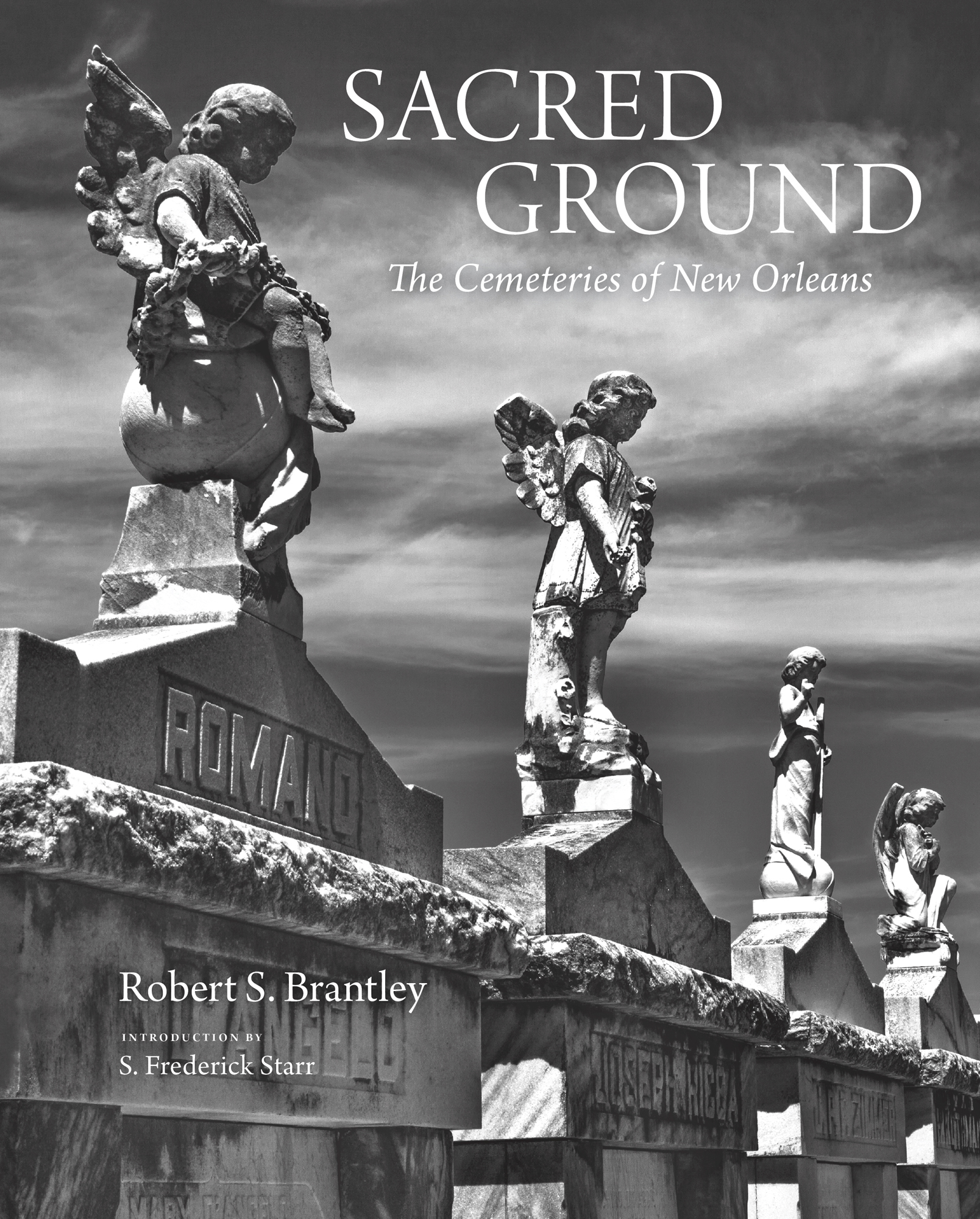

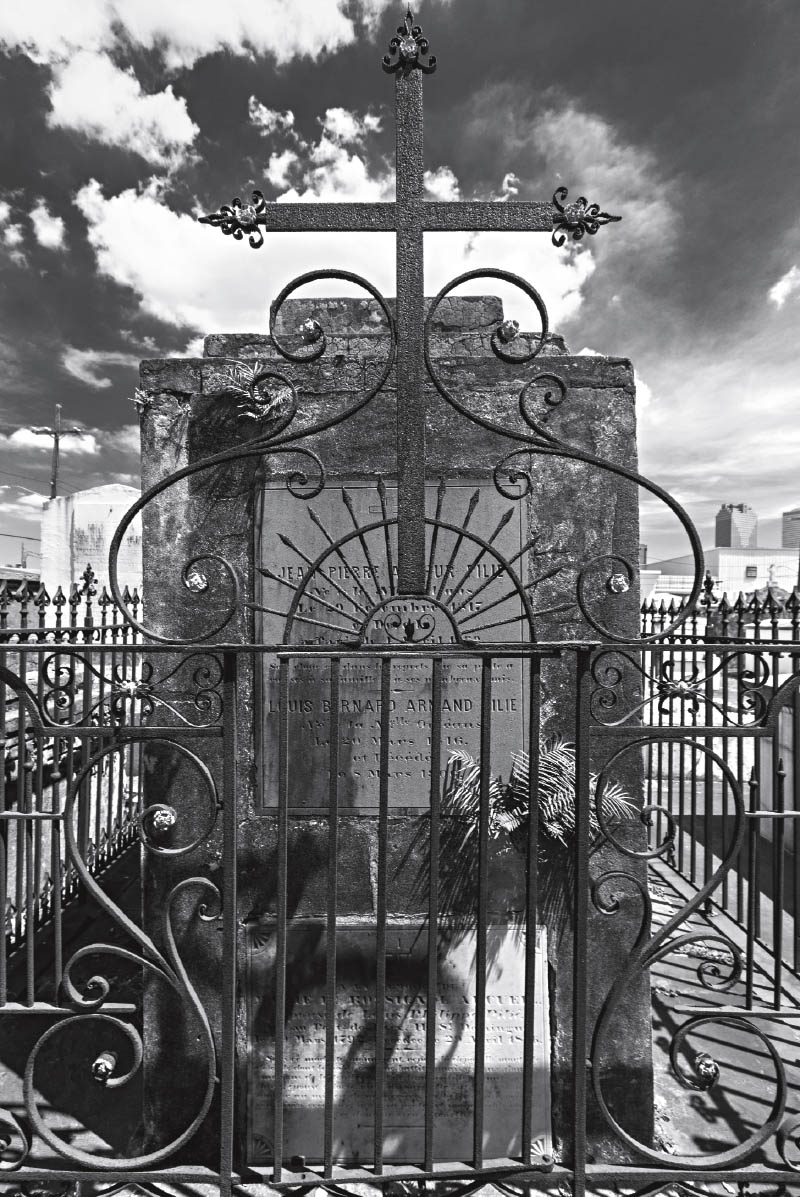

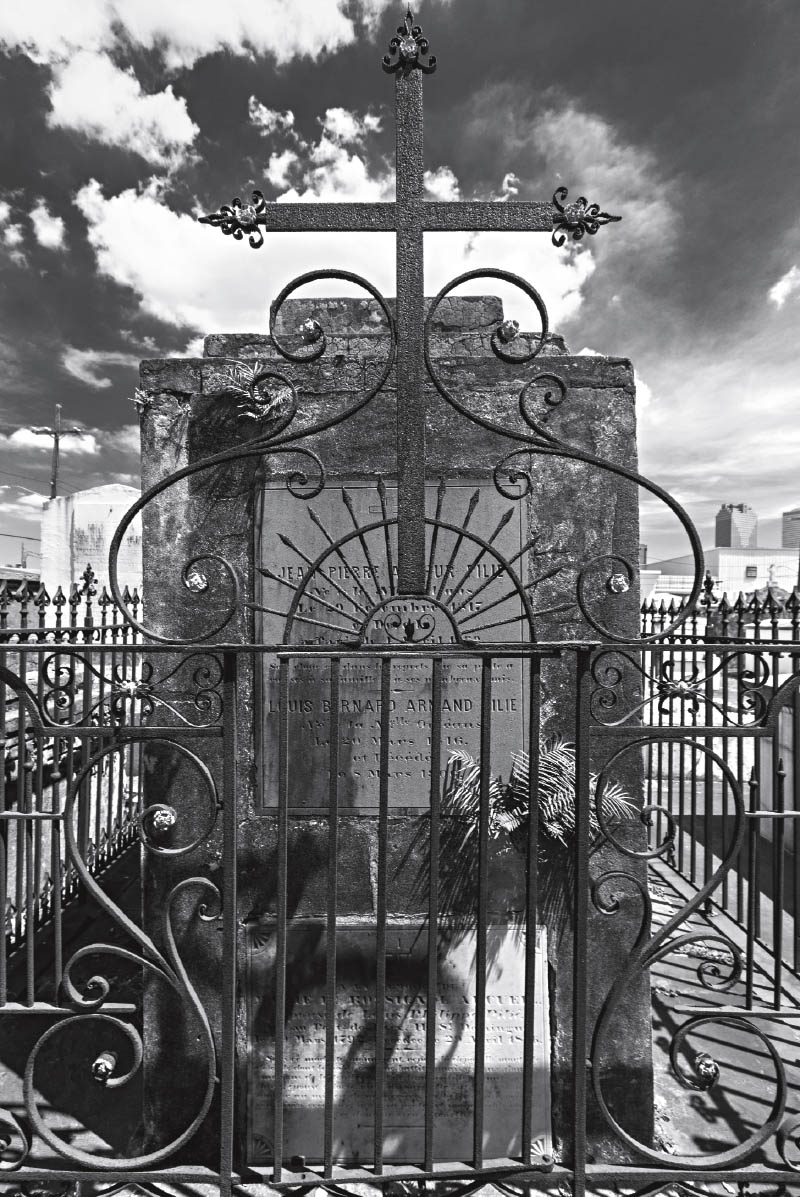

Wrought-iron gate, tomb of Jean Pili family, St. Louis Cemetery #2, Square 1

Monument of Irad Ferry, Cypress Grove Cemetery

To contain the periodic inundation of human remains, New Orleans borrowed from Spain the construction of wall vaults, each of which could accommodate tens or even hundreds of the dead. Resembling closed ovens, these came to be called oven vaults. Each consisted of up to a dozen small vaults placed side by side and surmounted by rows of further vaults, piled up in as many as four ranks. Within each wall vault was a flat surface for the corpse, behind which was a closed shaft to the ground, which enabled the proprietor or family to push out the bones left from earlier interments and make way for fresh corpses. As a result, a simple oven tomb consisting of a dozen vaults could house the remains of ninety or more of the dead.

The one human factor that most defined New Orleans cemeteries was the absence of easy transport up and down the Mississippi River before the 1830s and the resulting slowness of bringing goods from eastern ports by sail before the 1840s. Both were overcome only by the rise of steam-driven vessels. Only then could New Orleans think of bringing granite from New England, limestone from Indiana, and other stones from as far afield as Italy. Once this was possible, however, the modest old brick-and-mortar vaults quickly gave way to extravagant monuments and to fierce but unacknowledged competitions among their sponsors and namesakes.

Next page