Content

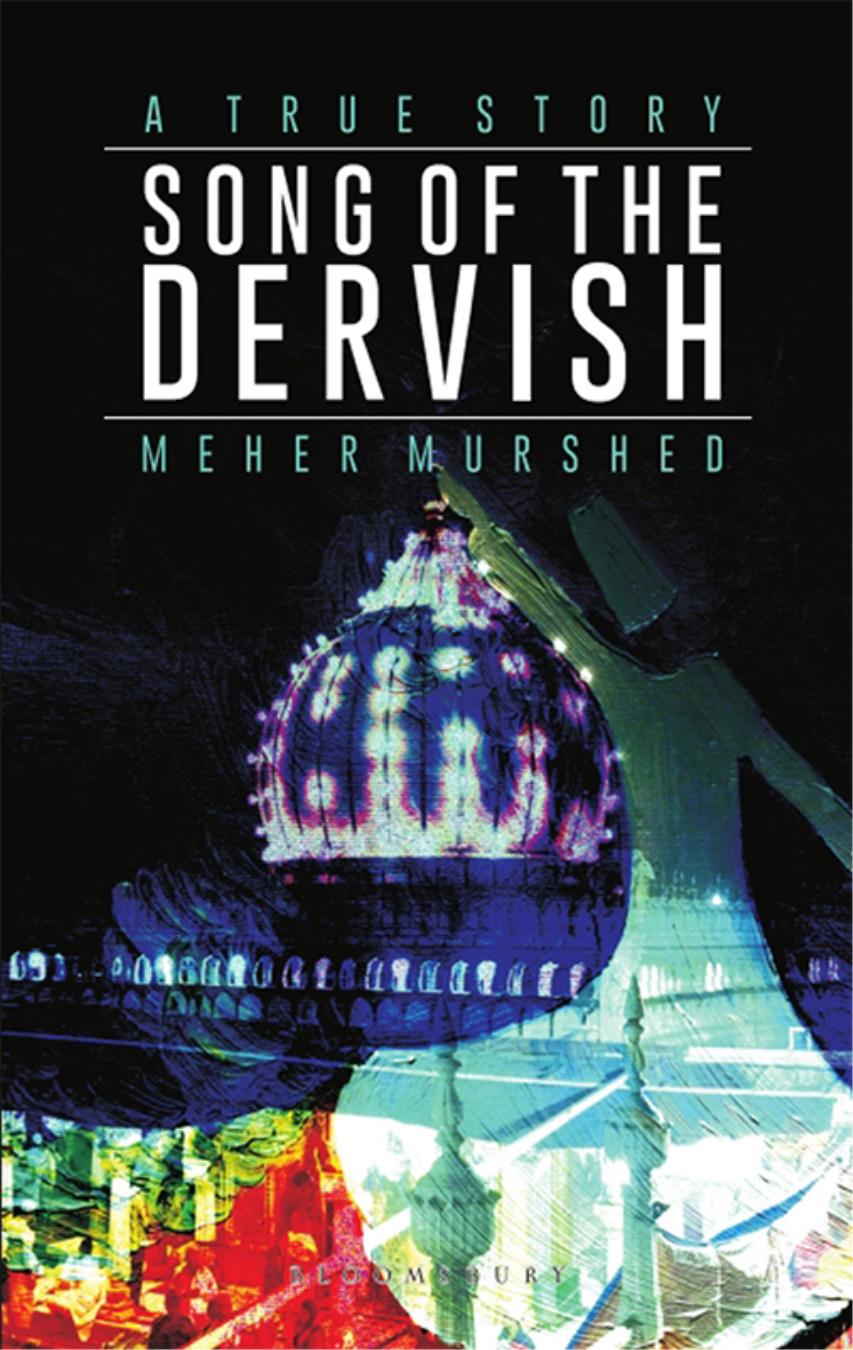

Song of The Dervish

Song of The Dervish

Meher Murshed

First published in India 2017

2017 by Meher Murshed

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

The content of this book is the sole expression and opinion of its author, and not of the publisher. The publisher in no manner is liable for any opinion or views expressed by the author. While best efforts have been made in preparing this book, the publisher makes no representations or warranties of any kind and assumes no liabilities of any kind with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the content and specifically disclaims any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness of use for a particular purpose.

The publisher believes that the content of this book does not violate any existing copyright/intellectual property of others in any manner whatsoever. However, in case any source has not been duly attributed, the publisher may be notified in writing for necessary action.

BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

E-ISBN 978 93 86432 05 6

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Bloomsbury Publishing India Pvt. Ltd

Second Floor, LSC Building No.4

DDA Complex, Pocket C 6 & 7, Vasant Kunj

New Delhi 110070

www.bloomsbury.com

Created by Manipal Digital Systems.

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com.

Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

Dedicated to:

For my wife Anupa, Rumpus and Simba, Sahib and Tennessee

The poet laureate of Pakistan remains the favoured Muslim poet of India. Mohammad Iqbal sang the praises of India long before he ever imagined that one day the Indian subcontinent would become the home to two and then three nations marked by religion. Iqbal was a mere youth at the turn of the twentieth century when he wrote a poem that became the song of India. It is a song that lauds both Hindustan and Gulistan: The best in all the world is our Hindustan; we are nightingales and this is our Gulistan. Hindustan, for Iqbal and for his generation, encompassed all Indians, from the Hindukush to the Bay of Bengal, from the Himalayas to the Arabian Sea. The nightingales were metaphors for those persons who enjoyed Hindustan as though it were a Gulistan or rose garden, whose aromas and beauty were ever to be celebrated in verse and song.

And for Iqbal as for other residents of Hindustan the chief nightingales in the rose garden of India were the Sufi saints, Muslim holy men who linked themselves to an Islamic worldview, with its own cosmology, its trajectory of truth, its emissaries and its hopes. Theirs was a complimentary rather than a competitive form of Islamic loyalty, since they shared the same imaginative as well as geographic space of India with Hindus and other non-Muslims.

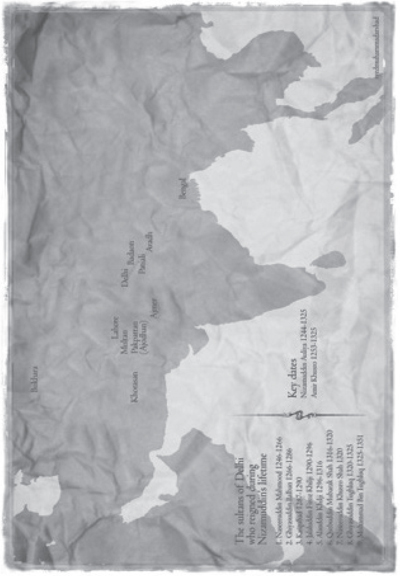

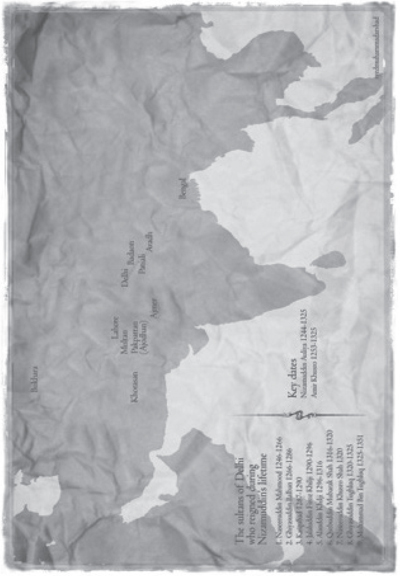

The best known order, the Chishtiya, had five epigones: Moinuddin, Qutbuddin, Fariduddin, Nizamuddin, and Naseeruddin. It is the fourth of these five, Nizamuddin, who occupies centerstage in this marvelous book. The life of Nizamuddin shares with all saint narratives a vision of the Unseen, the Unseen beyond time and place. That vision comes through intuitive knowledge. It is a vision not given to everyone. It is attained by those select few of who have dedicated their lives to service on behalf of others. They become luminous beings, spiritual guides on the Path (shaikhs or pirs). Shaikh Nizamuddin stands with other Chishti luminaries but also apart from them, nowhere more so than in his singular devotion to sama or listening to music.

Shaikh Nizamuddin was very fond of majalis-e sama or musical assemblies. Among his closest disciples was Amir Khusro, the Hindustani counterpart to Saadi of Shiraz. Amir Khusro and others wrote devotional poetry. On special occasions in the khanqah or retreat of the saint, disciples would gather to listen to the rhythmic recitation of this devotional poetry (qawwali) by a professional singer (qawwal). These majalis-e sama could induce ecstasy in listeners, so much so that Shaikh Nizamuddin, himself often moved to tears, considered ecstasy inspired by sama to be a source of spiritual nourishment. It is as though his life was itself a continuous song, and hence this book is aptly titled: Song of The Dervish.

Music was not a sport but a meditation, indeed, a goad to remember the Unseen in all that was seen and told, experienced and imagined, in thirteenth and fourteenth century Hindustan. While spiritual nourishment included sama, it also entailed supererogatory prayer, fasting, vigil, especially almsgiving. The notion that compassion was central to Islam meant that almsgiving could not be just a 10 per cent tithe; longing for God has as its complement care and consideration for all ones fellow human beings. In the words of Shaikh Burhanuddin Garib, the Deccan Chishti master who was a disciple of Nizamuddin: Our order is known for two things: love and compassion.

And that overflowing concern for others comes through verse as well as song. One cannot help but feel an expansive pathos when Shaikh Nizamuddin recites this verse from an earlier Sufi poet:

He who is not my friend

May God be his friend.

And he who causes me distress

May his joy increase.

He who places thorns in my path

With malice in his heart,

May every flower that blooms in the garden of his life

Be without a single thorn.

Poetry, like music, was no substitute for the rigours of a fully engaged Muslim life, yet it provided a glimmer of truth, intuited by the lofty soul of a devoted saint and transmitted to those closest to him. Shaikh Nizamuddin had disciples and successors, followers and admirers during his lifetime. Beyond his earthly life, they continued to relate to him through his tomb, a tomb that became the site of reverence and remembrance at the heart of this book.

The place where the master lived and taught in Tughluqabad, on the outskirts of Delhi, was known as his khanqah or zawiya. The place where the master was buried and remembered through prayers and pilgrimage, also in Tughluqabad, was his maqam or dargah.

Yet the dargah becomes more than a tomb site because those who come to pay their respects seek benefits from the saint. At the moment when the saint died it is believed that he remains most open to petitioners. That moment is celebrated annually as the urs, literally, anniversary of the saints marriage to God.

Visitors to the tomb of Shaikh Nizamuddin in Delhi have been continuous traffic, from the fourteenth to the twenty-first century. For nearly eight centuries, notes one observer, Shaikh Nizamuddins dargah has witnessed a continuous, uninterrupted flow of devotees and visitors. The shrine has provided the visitors, regardless of the distinctions of religion, caste and creed, spiritual solace and comfort, and a sense of communion and anchorage in the face of lifes inevitable uncertainties, anxieties and hardships. The