Plays One ( Forty Years On , Getting On , Habeas Corpus , Enjoy ) Plays Two ( Kafkas Dick , The Insurance Man , The Old Country , An Englishman Abroad , A Question of Attribution ) The Lady in the Van Office Suite The Madness of George III The Wind in the Willows The History Boys

Me, Im Afraid of Virginia Woolf ( A Day Out , Sunset Across the Bay ; A Visit from Miss Prothero ; Me, Im Afraid of Virginia Woolf ; Green Forms ; The Old Crowd ; Afternoon Off ) Rolling Home ( One Fine Day ; All Day on the Sands , Our Winnie , Rolling Home , Marks , Say Something Happened , Intensive Care ) Talking Heads

A Private Function ( The Old Crowd , A Private Function , Prick Up Your Ears , Boulevard Haussmann , The Madness of King George ) The History Boys: The Film (with Nicholas Hytner)

Three Stories ( The Laying On of Hands ; The Clothes They Stood Up In ; Father! Father! Burning Bright ) The Uncommon Reader

A Life Like Other Peoples

ALAN BENNETT

A FRANCES COADY BOOK

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

New York

A Life Like Other Peoples

Contents

There is a wood, the canal, the river, and above the river the railway and the road. Its the first proper country that you get to as you come north out of Leeds, and going home on the train I pass the place quite often. Only these days I look. Ive been passing the place for years without looking because I didnt know it was a place; that anything had happened there to make it a place, let alone a place that had something to do with me. Below the wood the water is deep and dark and sometimes theres a boy fishing or a couple walking a dog. I suppose its a beauty spot now. It probably was then.

Has there been any other mental illness in your family? Mr Parrs pen hovers over the Yes/No box on the form and my father, who is letting me answer the questions, looks down at his trilby and says nothing.

No, I say confidently, and Dad turns the trilby in his hands.

Anyway, says Mr Parr kindly but with what the three of us know is more tact than truth, depression isnt really mental illness. I see it all the time.

Mr Parr sees it all the time because he is the Mental Health Welfare Officer for the Craven district, and late this September evening in 1966 Dad and I are sitting in his bare linoleum-floored office above Settle police station while he takes a history of my mother.

So theres never been anything like this before?

No, I say, and without doubt or hesitation. After all, Im the educated one in the family. Ive been to Oxford. If there had been anything like this I should have known about it. No, theres never been anything like this.

Well, Dad says, and the information is meant for me as much as for Mr Parr, she did have something once. Just before we were married. And he looks at me apologetically. Only it was nerves more. It wasnt like this.

The this that it wasnt like was a change in my mothers personality that had come about with startling suddenness. Over a matter of weeks she had lost all her fun and vitality, turning fretful and apprehensive and inaccessible to reason or reassurance. As the days passed the mood deepened, bringing with it fantasy and delusion; the house was watched, my father made to speak in a whisper because there was someone on the landing, and the lavatory (always central to Mams scheme of things) was being monitored every time it was flushed. She started to sleep with her handbag under her pillow as if she were in a strange and dangerous hotel, and finally one night she fled the house in her nightgown, and Dad found her wandering in the street, whence she could only be fetched back into the house after some resistance.

Occurring in Leeds, where they had always lived, conduct like this might just have got by unnoticed, but the onset of the depression coincided with my parents retirement to a village in the Dales, a place so small and close-knit that such bizarre behaviour could not be hidden. Indeed it was partly the knowledge that they were about to leave the relative anonymity of the city for a small community where folks knew all your business and that she would henceforth be socially much more visible than she was used to (Im the centrepiece here) that might have brought on the depression in the first place. Or so Mr Parr is saying.

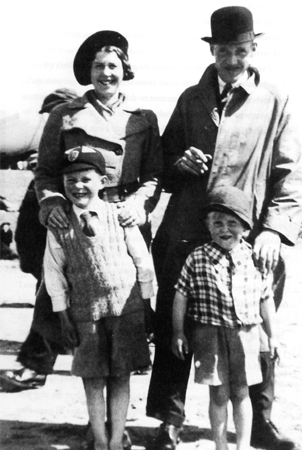

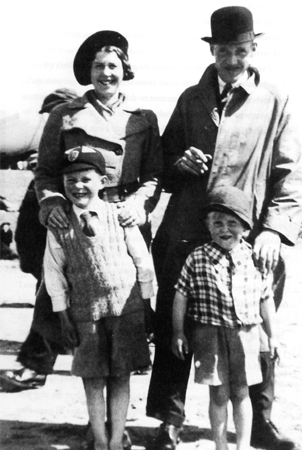

Mam and Dad in the back garden, 1966

My parents had always wanted to be in the country and have a garden. Living in Leeds all his life Dad looked back on the childhood holidays he had spent holidays on a farm at Bielby in the East Riding as a lost paradise. The village they were moving to was very pretty, too pretty for Mam in her depressed mood: Youll see, she said, well be inundated with folk visiting.

The cottage faced onto the village street but had a long garden at the back, and it seemed like the place they had always dreamed of. This was in 1966. A few years later I wrote a television play, Sunset Across the Bay , in which a retired couple not unlike my parents leave Leeds to go and live in Morecambe. As the coach hits the M62, bearing them away to a new life, the wife calls out, Bye bye, mucky Leeds! And so it had seemed. Now Dad was being told that it was this longed-for escape that had brought down this crushing visitation on his wife. Not surprisingly he would not believe it.

In their last weeks in Leeds Dad had put Mams low spirits down to the stress of the impending upheaval. Once the move had been accomplished, though, the depression persisted so now he fell back on the state of the house, blaming its bare unfurnished rooms, still with all the decorating to be done.

Your Mamll be better when weve got the place straight, he said. She cant do with it being all upset. So, while she sat fearfully on a hard chair in the passage, he got down to the decorating.

My brother, who had come up from Bristol to help with the move, also thought the state of the house was to blame, fastening particularly on an item that seemed to be top of her list of complaints, the absence of stair-carpet. I think I knew then that stair-carpet was only the beginning of it, and indeed when my brother galvanised a local firm into supplying and fitting the carpet in a couple of days Mam seemed scarcely to notice, the clouds did not lift, and in due course my brother went back to Bristol and I to London.

Over the next ten years this came to be the pattern. The onset of a bout of depression would fetch us home for a while, but when no immediate recovery was forthcoming we would take ourselves off again while Dad was left to cope. Or to care, as the phrase is nowadays. Dad was the carer. We cared, of course, but we still had lives to lead: Dad was retired he had all the time in the world to care.

The doctor has put her on tablets, Dad said over the phone, only they dont seem to be doing the trick. Tablets seldom did, even when one saw what was coming and caught it early. The onset of depression would find her sitting on unaccustomed chairs the cork stool in the bathroom, the hard chair in the hall that was just there for ornament and where no one ever sat, its only occupant the occasional umbrella. She would perch in the passage, dumb with misery and apprehension, motioning me not to go into the empty living room because there was someone there.