First published in Great Britain in 2019 by

The Book Guild Ltd

9 Priory Business Park

Wistow Road, Kibworth

Leicestershire, LE8 0RX

Freephone: 0800 999 2982

www.bookguild.co.uk

Email: info@bookguild.co.uk

Twitter: @bookguild

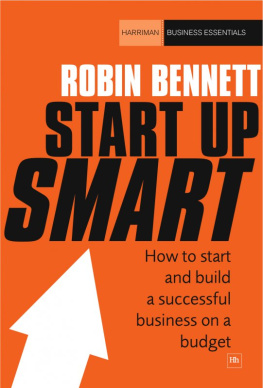

Copyright 2019 Robin Bennett

The right of Robin Bennett to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 97819132082640

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

To everyone Ive ever known: either in the best of circumstances or the less fortunate its all about how we are with others

A note on names

One of my concerns writing this book was I didnt want to embarrass anyone by their inclusion unless that was my stated intention. Ostensibly, this centred around my closest friends, who already have enough to put up with re me. So, I took the decision to change many key names of people who arent family, or simply not mention some by name particularly those individuals I still see regularly and especially where literal accuracy matters not a jot.

A further note on names

Changing names also disguises my ineptitude at remembering them: once in a video shop in Wales I had to hide behind a giant cut-out of Kung Fu Panda to avoid a cousin whose name escaped me, and whose wedding I had been to the year before.

Our children

For similar reasons (relating to privacy), I decided not to indulge in any discussions about our kids even description is a form of opinion, and their life is their own.

Contents

Prologue

This is a list of helpful Life Tips I sent to my goddaughter on her thirteenth birthday.

A quite surprising number of electrical things can be fixed by turning them OFF and then ON again.

Always do what needs to be done immediately. If youve got time to think about it, youve got time to do it.

Never miss an opportunity to go to the loo (this one is basically the same as the last one).

Polite and kind ALWAYS beats clever, and will win you more friends, jobs pretty much everything. Trust me on this (Im relatively stupid).

Learn not to worry everything sort of matters but no one thing matters that much. And the worst hardly ever happens anyway.

There are twenty-four hours in a day: sleep for eight, work for eight and play for eight.

Make friends with happy people.

If you dont know what to do about a problem, it means its not ready to be solved. Leave it until the answer comes. Youll feel it when it does.

Your parents are always on your side which I admit is hard to remember at times.

Loving is a kind of giving.

PS Always be kind to animals, as I know you will. It is the truest measure of a person.

Chapter 1

The incident with the goose

How to live with an eccentric

When I was about seven years old, my father woke one morning and told me, in all seriousness, that not another day could go by without him tasting the sweet flesh of a goose.

He packed me, our cairn terrier Judy, and his shotgun into our rusting Morris Marina and strapped a canoe onto the roof rack. Then he set off for the river.

I had my doubts even at the early stages of this enterprise: it was November and freezing cold. On top of this, my father had never expressed a craving for goose before, so I felt pretty sure it would soon pass if the call was left unanswered. However, at seven, you just kind of go along with things especially if your father is anything like mine.

We arrived at a bleak stretch of the Thames somewhere near Reading and prepared everything whilst watching the flock of Canada geese lounging about on an island in the middle of the river. Then we got in the canoe: me at the front with the dog; my father at the back, armed to the teeth.

The few walkers who were braving the weather that morning jumped in the air and looked about in alarm as the first shot rang out. Only the goose my father had picked for his dinner seemed unperturbed, as the pellets simply bounced off the thick mattress of breast feathers from twenty yards away.

Undeterred and completely unaware of the sharp looks he was getting from the bank, my father reloaded and paddled closer.

When the second shot rang out, taking the unfortunate gooses head off, people really stopped to stare.

Several things happened rather quickly after that:

My father (still armed) jumped out of the canoe, retrieved a limply flapping goose and threw it on my lap; he then jumped back in, sliding the shotgun down the side of the canoe; whereupon the shotguns second cartridge went off, with a sort of muffled bang; and we started to sink . My father panicked: he threw me onto the bank of the island, along with the dog; paddled as fast as he could across the river in a leaking boat; jumped out of the canoe with the shotgun in one hand, the dead goose in the other; and scampered towards the car.

Then he drove off.

It had been an eventful few minutes, but the next part of the morning went very slowly indeed as I stood on that cold island with the dog and wondered what would happen next.

Eventually a put-upon-looking lock-keeper appeared on the opposite bank, got into a small motor launch and made his way across to where I stood. He picked me up, muttering something about a phone call, and took me back to shore to meet my father whod had time to go home, wash the blood off and hide the goose.

Two weeks later, we would be sitting in front of the TV with trays on our laps watching Tom Baker being Doctor Who and stuffing our faces with goose. The whole operation was pronounced a great success.

I sometimes think that eccentricity is being possessed of more sharply defined contradictions. Take the last point in the prologue (about kindness to animals): murdering geese in broad daylight could, very justifiably, be taken to being the opposite of that yet it would be a task to find someone who likes animals more than my father, from our dogs to the tortoise. He even tried to bond with my sisters snakes, with their dead, prehistoric eyes and yearning for the small rodents we kept stashed in the fridge. But he also likes shooting and eating game, and brought me up to prize such free quarry over the miserable, mass-produced poultry in supermarkets.

True eccentricity is also a total unawareness of how you appear to others and the fact you are making a spectacle of yourself, and is the exact opposite of the Eccentric Presumptuous who gets up in the morning and puts on a loud bow tie precisely in order to get noticed.

If my father sported German lederhosen to mow the lawn in our quiet semi near Reading (which he did), took his dog into Mass (ditto), or obsessed about church architecture, whilst avoiding actual church like the plague, he did it for honest reasons of practicality or genuine desire never, ever for effect. That is the point. I remember his clog phase unfortunately coinciding with his pith helmet period: this was the closest he got to looking like a proper lunatic most of the time I thought he looked quite cool but that might just be a family thing. He was fortunate to have been born with enough charisma to get him out of most of the awkward situations his behaviour got him into, and he taught me that charm goes a long way.