First Bennett Books eBook Edition 2012

First Bennett Books (Revised) print Edition 2007

Compiled by Anthony Blake from the unpublished writings and talks of John G. Bennett.

Bennett Books

Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA

2012 The Estate of JG Bennett

All Rights Reserved. This book may not be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in whole or in part by any means, including graphic, electronic, or mechanical without the express written consent of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

ISBN: 978-1-881408-26-4 (eBook)

cover design, roberto duse /

cover image: Bob Jefferson

book design: AM Services

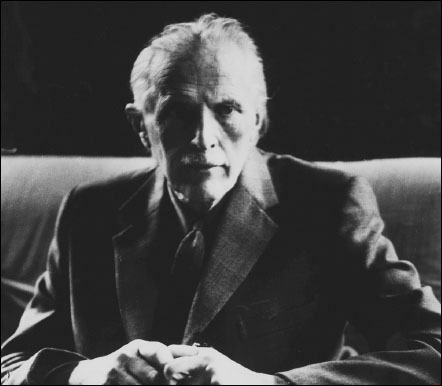

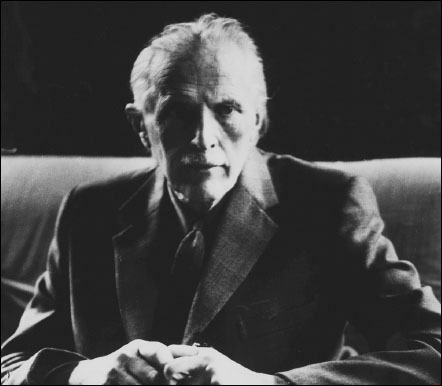

photo p viii: Anette Greene

CONTENTS

John Godolphin Bennett, 1973

Someone asks him a question about the publication of

Beelzebubs Tales. He speaks of his writings, and says that they

are his soldiers. With them he will make war against the old world. The old

world must be destroyed in order that a new world

may be born. His writings will make many friends but they will

also make many enemies. When they are published, he will

disappear. Perhaps he will not return. We protest that we cannot

work without him. If he disappears, we will follow him. He smiles

and says, perhaps you will not find me.

JG Bennett

The only way to approach Gurdjieffs masterpiece is to enter

into its creative nature, which is to discover new things at every

turn. Attempts to rationalize and explain the book are

tantamount to taming a wild animalfine for circuses but not

for anyone who loves nature. Bennett is someone who has

responded in a right way.

Anthony Blake

FOREWORD

The Prologue, which opens this book, as the Epilogue that closes it, was written by JG Bennett in 1950 to introduce a series of writings on the ideas of Mr. Gurdjieff, which also included A Study: Gurdjieffs All and Everything. These circulated amongst people in Bennetts groups but were never published. Their origin goes back to the year before, 1949, the period just before Mr. Gurdjieff died. Bennett described it as follows:

In 1949, Mr. Gurdjieff was living in Paris and his pupils were visiting him from all parts of the world. By far the largest contingent came from England, principally from the three groups led by Jane Heap, Kenneth Walker, and myself. I used to go as often as possible to Paris, and once a week held meetings at Denison House near Victoria Station for those who could not get to Paris. At that time, Mr. Gurdjieff spoke of coming to London and said that if he came, he expected the pupils to be familiar with Beelzebubs Tales to His Grandson. We therefore held weekly public readings of the book.

I told him that many had asked me to help them to understand the difficult words and even more difficult ideas in the book. He said that I should do so as well as I could, because he would be able to say what he wanted only to people who had thoroughly studied Beelzebubs Tales.

In June and July of 1949, Bennett gave six lectures just before he went to Paris for a prolonged stay, three months before Gurdjieffs death. Bennett began preparing these lectures for publication as late as 1973:

in spite of the development of my own understanding since they were given. At that time, I was in almost weekly contact with Gurdjieff and very much under the influence of the many talks I had with him about his works and his plans for the future.

Bennetts project was abandoned; and this compilation represents what might have been.

I was so deeply impressed by the extraordinary and powerful ideas of Beelzebubs Tales that I expected that when published they would make an instant appeal to those who throughout the world were searching for new concepts of God, the World and Man. In the event, the book that appeared about a year after these lectures made little impact outside the circle of those already interested in Gurdjieffs ideas. The book is too hard for the ordinary reader to take, and yet its message is for everyone.

Approaching the end of his life while teaching at The International Academy for Continuous Education, at Sherborne in Gloucestershire, Bennett gave many talks on the meaning of Beelzebubs Tales and luckily most of these were recorded. Some of these talks have been incorporated into this collection. The material spans almost twenty-five years, from 1950 until his death in 1974. The book is in six parts, for convenience arranged under the headings of Prologue, History, Cosmology, Cosmogony, Work, and Reality. The sequence of these sections is intended to correspond to a progression from general overview to practical method and from the prospect of superhuman intelligence to our acts in daily life. Cosmology is basically the law of three and cosmogony, the law of seven. Those interested in the difficult words Gurdjieff invented can track Bennetts interpretations from the index of this book.

What follows are some of my reflections now thirty years after this collection of essays was published, about which I can paraphrase Bennetts own remarks about Beelzebub and say: These essays made little impact even within the circle of those already interested in Bennetts ideas. Such is progress.

Reflections

When I first came across Beelzebubs Tales, I was astonished. The words seemed to have a direct conveyance of meaning and, as I read parts of the first chapter, The Arousing of Thought, I felt I was hearing the voice of the author and also the voice of consciousness itself. I did not need to try to understand what the words meant, because they acted directly. But sitting down by oneself and reading through the whole thing is not so easy. I was lucky in being around John Bennett who was able to pick up on threads and illuminate them, bringing them into the realm of possible dialogue rather than instruction. He also introduced me and many others to the experience of Beelzebubs Tales read aloud. I was not present when he underwent his marathon reading of the whole book with four hours on and four hours off, but had many chances to hear him read passages from it. At Sherborne, it was read through in hourly sessions before dinner and later, after Bennetts death, this wonderful duty fell to me. Later, I embarked on making a series of recordings from the book (still to be completed).

Gurdjieffs own advice to the reader was first, to read it like anything else, then to read it (as if) aloud and only then, finally, to grapple with its meaning. Reading aloud does something to the reader. In many ways, it is almost impossible to do correctly, as sentences elaborate into complex clauses, interweaving, replete with neologisms, and barely an allowance to take breath. Reading aloud is important because the reader has to use his body and breath and attention, giving them wholly over to the text. There would seem to be no time or space free to understand the text; its sheer performance taking all one can give. However, it is just under those conditions that some other kind of attention, some perception from eternity, comes into play.

This perception from eternity is won through physical effort. I believe it is the source of mythological thinking. Bennett, like Denis Saurat, quickly recognized that