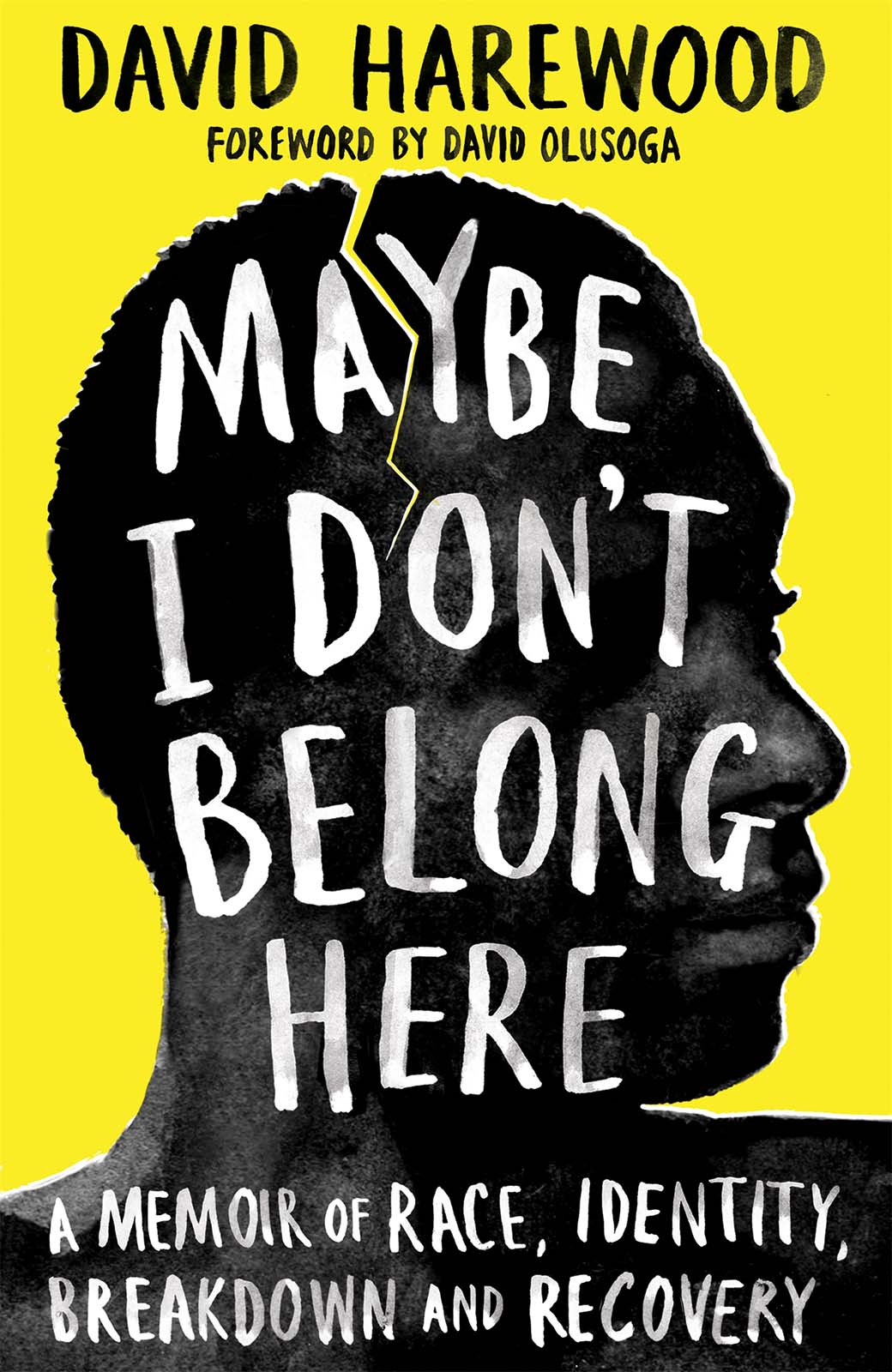

DAVID HAREWOOD

Maybe I Dont Belong Here

A Memoir of Race, Identity,

Breakdown and Recovery

Foreword by David Olusoga

Contents

To my father.

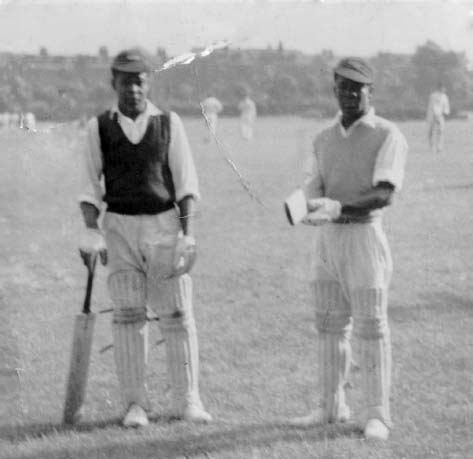

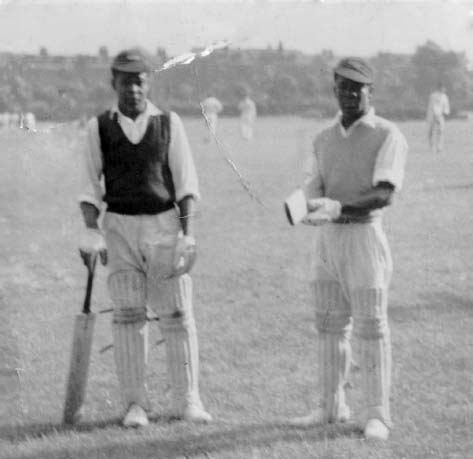

I was too young to understand what was happening to you when you were experiencing your struggle with mental illness, you rode out the storm alone. Its only now Ive written this book that I realise I never got the chance to sit and talk with you about the times those rough winds ripped through our minds. In that respect, Ive realised this all too late. I went away to follow my dreams, life and work taking me to other places, and though I did my best to get to see you whenever I could it was never enough. Thank heavens for Sandra. And when another storm came to ravage your mind, this time blasting away your capacity, came a time when it was just enough to sit with you and see the occasional spark in your eye. You were still Dad.

I was in America when I heard the news, heard the news the storm was over. Youd found peace, finally, a place to rest after your long, hard journey, sheltered away now, protected from the harsh winds. Get some sleep, Dad. Thank you for the car rides, the truck trips and the jacket. Thank you for the train pass and for signing the paperwork I needed to secure my grant to go to RADA. You set me up in so many ways, Dad, Im not sure if I ever I got the chance tell you. I hope you knew it, they all know it now.

This is for you, Dad. Sleep well.

Foreword

W hen I first met David Harewood, we spoke incessantly for over an hour. We were attending a television industry party, a plush gathering in which guests are expected to circulate and network; the savviest amongst them seeking out valuable face-time with influential commissioners and channel controllers. What you are not supposed to do at such events is enter into a long and intense conversation with a single person to the exclusion of everything and everyone else.

I wanted to talk to David Harewood not because he is a Hollywood actor or the star of TV dramas; the room was full of other famous people. I wanted to talk to him about a season of TV programmes that we had both, separately, appeared in, the previous year. My part in that season had been a documentary in which I had returned to the street in which I had lived as a teenager, back in the 1980s. That street is the site of the home where my inter-racial family had been forced out after a relentless campaign of attacks launched by the thugs of the National Front. This confrontation with my own past had been important and necessary. By being open about my own experiences I was able to demonstrate to viewers how deep the wounds left by racism can run, lingering on decades after the events in question. It had made the documentary more impactful.

Yet despite my professional rationalisation of my decision, when the series was broadcast I felt extraordinarily exposed and uncomfortable. A painful experience I had rarely discussed even with my mother and siblings suddenly became public knowledge. I was asked to speak about it in radio interviews and comment about it in newspapers. Talking about racism publicly, not in the abstract but in raw and personal terms, made me feel that I had broken some unwritten, self-imposed rule. Not long after the series was broadcast, in the midst of my discomfort, I watched another documentary that was part of the same season. Within that programme, to my intense relief, David Harewood gave an interview in which he too spoke candidly of his encounters with British racism. As David recounted shocking experiences from his past, describing them in stark detail, suddenly I felt less alone and less exposed. Davids decision to talk openly about what had happened to him seemed somehow to validate my own. I later discovered, from the letters and emails sent by viewers who had watched that season of programmes, that other people of colour had been deeply affected by watching well-known (and in David Harewoods case A-list famous) Black people discussing racism and its impact upon their lives in such frank and personal terms.

Meeting David Harewood a year later at that party gave me an opportunity to explain what his openness had meant to me, how it had reassured me that my own decision to discuss my past had been the right one. We talked about why it was we had never previously felt able to discuss such experiences publicly, and of how so many other Black people had similar stories to tell; stories that only seemed to emerge occasionally and always in private settings. Like many Black people who had encountered the racism of Britain in the 1970s and 1980s, David and I had locked away not just our memories of racist incidents but also, and perhaps more importantly, our memories of how these events had been damaging assaults on our sense of self.

In this book David Harewood writes with rare honesty and fearless self-analysis about exactly such experiences; his upbringing and his encounters with racism from childhood onwards. He explores how the hostility of strangers collided with his developing sense of self and his relationship to Britain and with his own Blackness. Such experiences, combined with other factors, ultimately led to what David describes as the deepest darkest moment in his life; his descent into psychosis at the age of 23.

With equal candour David plots the story of his recovery; a long journey that took him from Birminghams Hollymoor Psychiatric Hospital to the lights of Hollywood. This book is, in itself, a physical manifestation of that hopeful journey, the process of writing these pages demanding the painful disinterring of long-buried details from Davids darkest of moments and a confrontation with the contents of a file containing the medical records from his weeks in Hollymoor Hospital.

The reticence felt by many Black Britons when it comes to talking frankly about their experiences of racism and racial violence is very often accompanied by an even deeper resistance to discussing the issue of mental health. Yet the need for such discussions are arguably greater and more urgent amongst Black Britons than any other demographic. Within Britains Black communities there exists a mental health crisis, the details of which are largely debated through statistics. Those numbers reveal, amongst other things, that Black people in Britain are far more likely than white people to suffer forms of mental ill-health that lead to them being hospitalised. However, no matter how shocking such statistics might be, and no matter how skilfully and sensitively they are deployed by journalists and the authors of reports, they remain just statistics, mere numbers that are incapable of conveying the human toll of this crisis. By bravely recounting his own experiences, of both his psychosis and his recovery, David makes real and tangible a phenomenon that too often is met with hushed silence and inaction.

Some readers might be surprised that a memoir written by such a celebrated actor explores the politics of race and diversity as much as the craft of the stage. Yet in our society when a Black person writes or speaks about race and racism their words are always regarded as political. Even today, after the murder of George Floyd and the great wave of protest, learning and acknowledgement that followed, there are still people who with no sense of embarrassment confidently assert that they just dont see race, encouraging others to affect a similar myopia. To entertain that particular delusion and to imagine oneself capable of that specific impossibility is also to proclaim enormous privilege.