Copyright 2021 Henry M. Silvert

An Indelible Event and Detour Through a Global Childhood: A Memoir

Soft-Cover ISBN: 978-1-09835-699-6

eBook ISBN: 978-1-09835-700-9

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021905341

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

Contents

To Morrie, My Soul Mate and the Love of My Life

Preface

F or days, I sat and stared at my computer screen, wondering how I was going to find the information I sought. Morrie, my wife, suggested Googling it. Yes, but which search words to use? The matter gnawed at me as I went about my daily life. Then, the answer suddenly announced itself in a dream. At 7:30 the next morning, my adrenaline rushing, I turned on the computer and searched New Orleans newspapers.

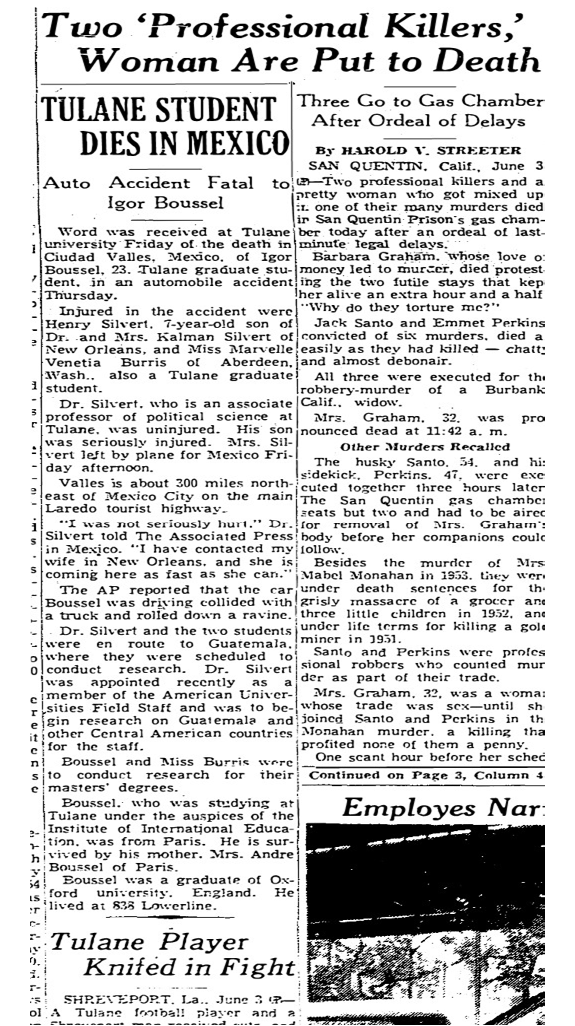

I thought that if the information would be anywhere, it would be in the archives of one of the citys newspapers, however the list of links was a long one. Which one to choose first? Instead of overthinking it, I asked myself which newspaper would most likely contain the information I wanted. The most rational click was the newspaper I knew best. My only concern was that the records might have disappeared during Hurricane Katrina. Luckily, I hit the jackpot on my first try! I was shocked to find the article smack in the middle of the front page of the Saturday, June 4, 1955 Times Picayune . It was only ten extremely short paragraphs but contained all the information I had sought for so long. Squeezed next to stories about executions in San Quentin and an article about a knife fight involving a university football player was an article titled Tulane Student Dies in Mexico. The article provided details about an automobile accident a few hundred miles north of Mexico City that involved a professor, his son, and two graduate students. It said that the car had collided with a truck and rolled down into a ravine. The article noted that the Tulane professor, who was not seriously injured and was able to call his wife, was appointed recently as a member of the American Universities Field Staff and was to begin research on Guatemala and other Central American countries. The others in the car did not fare as well. The student who was driving lost his life, and the student sitting next to him and the boy stretched out sleeping on the backseat sustained severe head injuries.

Reprinted with permission from The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate

I was that boy, and I was not yet seven years old. My father Kalman was the professor. This article was a bonanza for me. It matched the little that my parents had told me and added a few interesting details about the accidents location. Before the accident, I was, according to my parents, an ornery, creative, precocious, and somewhat nerdy kid. I especially enjoyed playing the violin, which I started learning at the age of three, and playing contract bridge with my friends after rough games of hide-and-seek and tag. The accident changed all that.

I lost all memory of everything that had come before. Because I didnt know which skills I had acquired before the accident, once I remastered the basics, I took most things in stride. I let other people teach me the things that they thought I should know at the speed they thought appropriate. I was a blank slate absorbing peoples input because I had no other knowledge to counter theirs. Recuperation was a long, tedious, exasperatingly slow, frustrating, and seemingly never-ending process. Looking back, these many decades later, I can see how the insistence of my parents and two brothers, Benjamin (Benjie) and Alexander (Ali), that I could do anything I set my mind to, kept me on the steady path toward improvement.

At the start of the relearning process, I had no choice but to do what I was told. No was not initially part of my vocabulary, and even after I learned and started using the word, those helping me would continue to nag, nag, nag until I invariably succumbed. In the end, even though the struggle to reinvent myself was at times a dauntingly painful and long chore, I also found the experience joyful and exhilarating. Despite the accident, or perhaps because of it, I focused on the possibilities of things not yet achieved rather than on the difficulties of realizing them. It was tedious learning how to walk and run again, but it was thrilling to eventually dance and play football, basketball, and table tennis. Ultimately, I was able to learn to play the violin and bridge again, but first I had to master what had been taken for granted: sitting up, talking, and comprehending what was said to me, as well as eating with utensils, reading, writing, and simply being able to think.

Some kids and adults teased me because I limped, my eyes were crooked, and my speech was slow and choppy. To my mind, they were shallow and rigid. By taking this attitude, I developed a stubbornness that empowered me to perceive the immense possibilities of lifes beauty. The constant reminders from my tormentors that I was different and the continual conflict that it caused within me resulted in a type of force field that I built around myself. This impenetrable shield protected me from the naysayers, the teasers, and the bullies. Whenever someone managed to dent this protective layer with evil words, deeds, or a fistfight, my family was always around to help me. My perceptions of myself, of my small circle of friends, and of the world in general were framed in large part by the ways my family shielded me from the negativity of those who asserted that I would never amount to anything. To their credit, my parents never gave up their hope su esperanza that I could overcome many of the limitations that the accident caused. From the start, both of them were extremely obstinate toward those who said I would never even recover from a vegetative state.

Stubbornness runs deep in my family, and my parents were not going to give up on their dreams for my future. My fathers persistence was subtle and largely directed toward my intellectual development, while my mother had an unyielding and adamant belief that I could do whatever people told her I couldnt. Even my brothers, although I wouldnt learn about it until years later, defended me against high school bullies. In the end, my fathers continued encouragement, my mothers defiant attitude, and my brothers protection helped me break free.

The accident itself, however, remained a relative mystery until I found the Times Picayune article. Both my parents apparently felt that it was better not to utter a word about the details of the accident to me in fear that I might be too traumatized. Maybe it was because they were the ones who were too traumatized. I did not know until my mother told me in September 2001, shortly before her death, that, until he died in June 1976, my father carried a great deal of guilt for the accident.