Sections of material have been adapted from articles that I wrote for the magazines NorthandSouth and the Listener, so my special thanks are also due to their editors, Robyn Langwell and Finlay Macdonald.

I am grateful also to Caroline, Bill and Sam Ireland, and for conversations and communications with Neil and Tony Perrett, Colin Crawford, Jack OConnell, Kasmin, Bridget Armstrong, Anthony Stones, Ray Grover and Jill Reed.

And at least a billion more thanks are due to Harriet Allan, whose astute advice at Vintage made this memoir, and its earlier companion-volume , possible.

This is not an autobiography. It does not attempt to present a full account of a life; it does not dwell on events or achievements; it does not propose explanations or excuses; it does not examine or interpret motives; and it is deliberately selective. It is a memoir, derived from impressions, conversations , anecdotes and poems, and its vague focus is a trip to Eastern Europe that I took by chance in 1959.

The narrative leads indirectly and haphazardly towards and away from this single happening, not because I think it important in itself, or even central to my existence for there are several other, equally erratic, ways that I might have shaped this story but because it helped change me as a writer and, far more significantly, because it has lately begun to suggest that I may once have had a little-noticed, but uniquely privileged, personal observation point from which I now sometimes imagine that I may have caught a whiff of the odours and a flicker of the shadows of the times through which the whole world drifted.

It was a lucky break, for the place, the people and even the tang in the air were different then. In the 1950s, and especially the 1960s, life on Earth altered and not just in attitudes, styles, relationships, beliefs, values and expectations, or in the dynamics of its many languages. Sometimes I think the planet must have been wobbling almost off its axis.

Yet I have tried to keep reminding myself that all such impressions can only be discriminatory and distorted. We may revisit moments in the past, but they cannot be relived. Even the most meticulous historian is never going to get the facts exactly right. He or she will always impose discriminations , interpretations and suppositions. But this is part of their interest. We re-humanise our yesterdays by our efforts to re-enter them.

In this record I have altered a couple of names, but the rest is the truth as I remember it. The omissions may be considerable, but my excuse for them is that they would have jam-packed the tale and obscured whatever pattern it now possesses. Most of my old friends and great occasions belong to another set of markers that may one day disclose a pathway towards a new point of view.

The single thread I have held to as this tale has unravelled is the process of recollection itself. My previous memoir, UndertheBridgeandOvertheMoon, was also underpinned by a single event, the break-up of my family, but I was able to use that narrative device in a fairly straightforward chronology, for we usually perceive our family history in terms of progress and development, and we reconstruct the events of our childhood and youth in a linked sequence of awakenings, or as a series of steps towards independence and insight. Adult storylines seldom work like that. This one occasionally moves backwards and forwards in time, for that is how we recall our more recent yesterdays.

My method was to go to my desk each morning and simply jot down a record of each episode from my past as it came to me in the early hours, mostly in moments between sleeping and waking. This is a manner of working that many writers follow, but in addition I have tried to preserve the basic structure and chronology of the record, going back only to correct and amplify. It seemed to me, from the beginning, that I should not try to alter the erratic shape of remembrance.

The test is this: there is a devious mechanism in the mind that sets its own times precisely. It is best left alone. When it is fiddled about with, it stops ticking. I have tried to keep listening for it. The sound is faint. It is measured in heartbeats.

It was disgraceful. In fact, it was a lot worse than that; it was the next best thing to a flagrant outrage. What happened was that one day, in a flash of unforgivable forgetfulness, I gazed straight at my first wife, whom I had lived with for a decade, and I failed to recognise her. I didnt have the slightest clue who on earth she could be.

This astonishing lapse of memory occurred in just about the oddest place imaginable. Donna and I had been divorced for several years when by chance our paths re-crossed at the SAS headquarters in the Chelsea Barracks, near Sloane Square, London.

The stone barracks building was forbidding and gloomy, which was entirely appropriate when I think about it now. And the interior was scarcely different. The main hall was stripped bare, for it was obviously being used regularly for exercises and training, though at one end, in an entrance alcove, there was a small bar, serving beer and spirits.

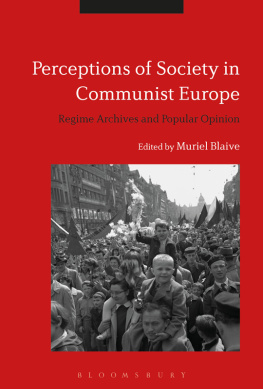

This drinks facility was run by a snooty, though immaculately turned-out , steward. The sole decorations in the main hall were a collection of large political posters that must have been snaffled from behind the Iron Curtain. They included a scowling portrait of Lenin and a series of cartoonish, zombie-like representations of heroic workers and peasants, gesturing menacingly towards a glorious future.

In my experience of life in Eastern Europe, these posters were not just a waste of public money, they were totally counter-productive. Their stylised, dehumanised images were plastered everywhere and were detested, even by some of the loyal Communists I spoke to. They seemed designed to browbeat, depress and alienate the populations at which they were aimed. It wasnt difficult to understand how their intimidating exhortations and grim contempt were being used to fire up the anger and commitment of the SAS recruits.