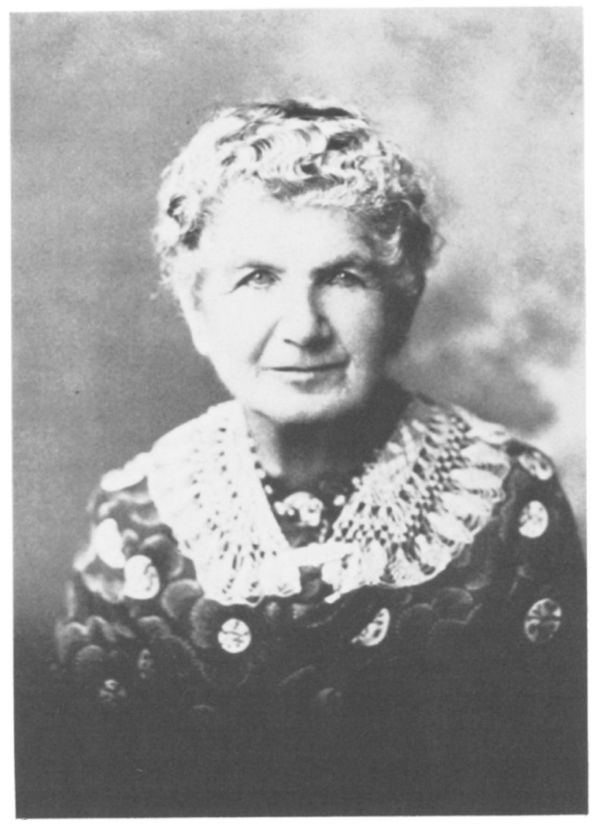

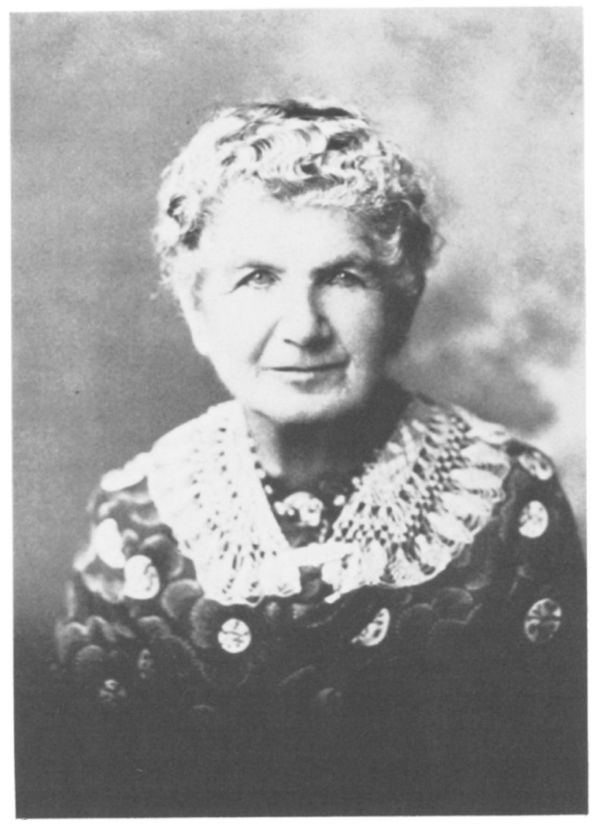

MARY ANN HAFEN

Taken in 1931, at the age of seventy-seven

Introduction 2004 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First Nebraska paperback printing: 1983

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

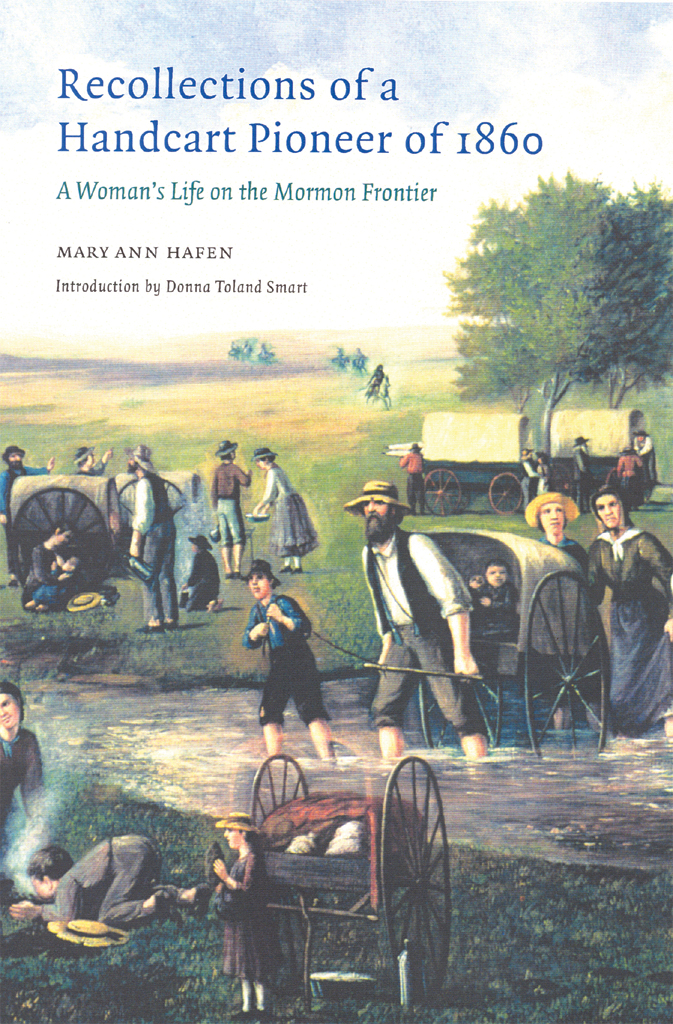

Hafen, Mary Ann, 1854

Recollections of a handcart pioneer of 1860: a woman's life on the mormon frontier / By Mary Ann Hafen.Bison books ed.

p. cm.

Originally published: Denver, 1938.

ISBN 0-8032-7340-1 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Hafen, Mary Ann, 1854- 2. Mormon pioneersUtahBiography. 3. Mormon pioneersNevadaBiography. 4. Frontier and pioneer lifeUtah. 5. Frontier and pioneer lifeNevada. 6. Mormon handcart companies. 7. UtahSocial life and customs19th century. 8. NevadaSocial life and customs19th century. 9. UtahBiography.

10. NevadaBiography. I. Title.

F826.Hl4 2004

979.2'02'0092dc22

2003028177

Reprinted from the privately printed first edition (1938), omitting Appendix B, Family Record.

This Bison Books edition follows the original in beginning the foreword on arabic page 7; no material has been omitted.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

DONNA TOLAND SMART

INTRODUCTION

I shall try to present them [the Mormons] in their terms and judge them in mine. That I do not accept the faith that possessed them does not mean I doubt their frequent devotion and heroism in its service. Especially their women. Their women were incredible.

When he wrote this, Wallace Stegner surely meant women such as Mary Ann Stucki Reber Hafen. When she was close to eighty-four years old, she indulged her family by writing a sketch of her life. This charming, information-packed little book was first published in 1938 by the Hafen family. In a brief explanation Mary Ann credits her descendant historians, son LeRoy (as well as his wife, Ann Woodbury Hafen) and her granddaughter, Juanita Leavitt Pulsipher Brooks, with assisting her since having been reared under pioneer conditions, with little opportunity for schooling, I felt unequal to the task (p. 7). Although originally intended for the family only, this volume constitutes its seventh printing. Astounding Could she have imagined that her remembrances would turn into a small classic?

The trail account is unique only in the particulars and because of the relatively small percentage of pioneers who recorded their experiences or their memories. Many thousands of women and children crossed the plains by wagon or handcart before the coming of the railroad in 1869. In Childrens Voices from the Trail , historian Rosemary Palmer estimates that one-fifth of [all] the overlanders were young people.

Of course, six-year-old Mary Ann was not playing among the wagons, since she walked with a handcart company. But despite the inevitable weariness, probably she played more than she worked.

The main title to this volume is misleading, since the recollections extend far beyond 1860, into Mary Ann's old age. Although Mary Ann's family pushed or pulled their cumbersome handcart across the prairies, forded the rivers, and toiled up the mountains from July 6 to September 24, 1860, the handcart project had begun in 1856. It was financed by a payback agreement called the Perpetual Emigration Fund, which bore the small cost of the journey. On the whole, the concept could be judged successful, since out often companies, only the Martin and Willey companies suffered major difficulties and an astounding number of deaths. The 1860 handcart crossing in which the Stuckis traveled was historic in that it was the last. There after teams and wagons were sent from Salt Lake City to the Missouri River and back in one season to transport emigrants and their gear. Indeed, the appeal of Recollections , with its history of the fight to survive in the desert landscape of southern Utah, significantly surpasses the details of the handcart saga, however fascinating.

Imagine sitting at the fireside of octogenarian Mary Ann as she talks and answers questions now and again. You might for an hour feel like you are one of her precious posterity, enjoying her chattiness, her frankness, her unabashed faith.

However eagerly her children and grandchildren offered hints, or later took a red pen to the original manuscript, the voice of Mary Ann speaks with unmistakable honesty and a desire to leave her mark on her loved ones. Such qualities override any editor. No matter how much polishing took place, LeRoy, Ann, and Juanita could not trifle with her true tone.

The first compelling characteristic for the unrelated reader, then, is a feeling of being Mary Ann's confidant. She trusts you enough to tell you about herself. She shares her most personal faith, from her parents' conversion to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormon), to witnessing the healing of her uncle, John Reber, whom she married years later and whose tragic death she endured only days after their wedding, to her courageous acceptance of life's vicissitudes, to her vision of the Savior, to her own fascinating dreams and their self-interpretations, to her final testimonyshe never wavers from that guileless faith. Founded on visions, revelations, and dreams, her church allowed her to believe in such phenomena on her own behalf and to live accordingly. Nevertheless, though told with quiet restraint and submissiveness, Mary Ann's strengths surface on every page of her story, and you find yourself admiring her tenacity and faith.

In addition to divulging her spiritual side, Mary Ann peoples her memories with noteworthy friends and acquaintances. Most of them are unknown, but some how recognizable . You may not know their full names; you may not know how they fill their ordinary days, but you accept them because Mary Ann casually introduces them to you. At least three of the menJacob Hamblin, Dudley Leavitt, and Edward Bunkerwere crucial forces in the settling of the places where she lived.

Mary Ann's gift of description adds a natural charm and makes her memoirs captivating. She transports youto Switzerland and her family's simple farm nestled near the soaring Alps; by boat to New York City with its towering buildings; by handcart to the arid Great Basin; by wagons to the red soils of Dixie and Santa Clara, Utah, and to tiny Bunkerville, Nevada, beside the unpredictable Virgin River. In 1920 she enjoys the luxury of riding in an automobile to Salt Lake City and later to Boulder (Hoover) Dam. In 1931 she takes a train to Denver, where her son was state historian and curator. She also saw the Pacific Ocean when she made a trip to Berkeley, California, while her son was in school there.

Although her descriptions are compelling, embellishment is not her style, nor is exaggeration. For example, when she is moved to Bunkerville in 1891 she found the big lot already had five or six almond trees growing, and a nice vineyard of grapes. But there was a little wash running through the side of the lot which had to be filled in; and there was only a makeshift fence of mesquite brush piled about three feet high. Besides, the lot was covered with rocks, because it was close to the gravel hill (p. 73).