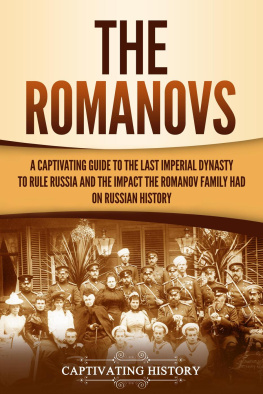

Lula and Silas

The Ai-Todors

The Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna,

mother of the Tsar 1847-1928

Grand Duchess Xenia, sister of the Tsar 1875-1960

Prince Dmitri, nephew of the Tsar, son of Grand Duchess Xenia 1901-1980

Prince Vassily, nephew of the Tsar, son of Grand Duchess Xenia 1907-1989

Princess Irina, niece of the Tsar, daughter of Grand Duchess Xenia and wife of Prince Felix Youssoupov 1895-1970

Prince Felix Youssoupov, murderer of Rasputin 1887-1967

The Dulbers

Grand Duke Nicholas, or Nikolasha, cousin of the Tsar 1856-1929

Grand Duchess Anastasia, wife of Nikolasha 1868-1935

Grand Duke Peter, brother of Nikolasha 1864-1931

Grand Duchess Militsa, wife of Grand Duke Peter 1866-1951

Princess Marina, daughter of Peter and Militsa 1892-1981

Prince Roman, son of Peter and Militsa 1896-1978

Princess Nadezhda, daughter of Peter and Militsa, wife of Nicholas Orloff, 1898-1988

Further Passengers

Prince Felix Youssoupov (sen), Felixs father, former

Governor of Moscow 1856-1928

Princess Zenaide Youssoupov, Felixs mother 1861-1939

Princess Sofka Dolgorouky (later Skipwith), granddaughter of the Dowagers best friend, Baroness Dolgorouky 1907-1994

Prince Nicholas Orloff, 1891-1961

Prince Serge Dolgorouky, equerry to the Dowager 1872-1933

Countess Zenaide Mengden, Empresss lady-in-waiting, 1878-1950

Princess Aprak Obolensky, Empresss lady-in-waiting, 1851-1943

Miss Henton, or Henty, governess and nanny to the Youssoupovs 1866-1940

Miss Coster, or Nana Coster, governess and nanny to Grand Duchess Xenias children

Miss King, governess to the Dolgoroukys

Officers

Captain Charles Johnson 1869-1930

Commander Henry Tom Fothergill 1881-1963

First Lieutenant Francis Pridham 1886-1975

April 7th, 1919

As the light of a brilliant Crimean day began to fade, a picturesque group gathered on the beach below the imposing estate of Koreiz. At its heart were 17 members of the Russian Imperial Family and their entourages, including five small children, six dogs and a canary.

Among the principal Romanovs were the Tsars mother, the Dowager Empress Marie, and his sister, the Grand Duchess Xenia. The resemblance between mother and daughter was immediately obvious; both had an air of defiance about them, evident in everything from the way they stood to their strong facial features.

Once crowned Tsarina of all the Russias, the elder woman now rejected all flamboyance in her dress; she and her daughter both chose to wear inconspicuous, dark clothes. Later that evening, the pair would walk the decks of a British battleship unrecognised and unnoticed. Their identity would emerge only when the mortified officer in charge noted a further likeness: the Dowager greatly resembled her sister, Englands Queen Alexandra.

The Dowager and her daughter, clutching her pet dog Toby, were among the last to make their way to an ornate jetty. Both were struggling with their emotions. The Dowager later described their feelings: What grief and desperation Poor Xenia was weeping dreadfully.

Prior to the arrival of the two women, the group had been dominated by the Tsars dread uncle, the colossal Grand Duke Nicholas. The Grand Duke, former Commander of the Russian Army, seemed to make a point of staking his claim as first at the quay. In dramatic, almost aggressive, contrast to the women, his appearance was eye-catching and intimidating . He stood, an imposing six feet seven, in full traditional Cossack military uniform, with Circassian coat and medals.

He was accompanied by his reedy brother, Grand Duke Peter. This younger Grand Duke distanced himself from his brothers war-mongering appearance, preferring conventional Edwardian clothes, glasses and a deer-stalker hat. Beside him stood two of his three children: the ascetic- looking Prince Roman, 22, and cheery Princess Marina, 27.

The two Grand Dukes were accompanied by their wives, both Princesses of Montenegro, known jointly as the Black Peril. The brothers contrasting proportions were reflected in their choice of sisters: Grand Duke Nicholass wifes face was as round and robust as her sisters was long and drawn.

Hardly less captivating, at some distance from the Grand Dukes and their entourages, stood members of Russias wealthiest family: the Youssoupovs. Prince Felix Youssoupov, a nephew by marriage of the Tsar, was best known as the man who had killed the controversial holy man Rasputin.

This fabled murderer also had a reputation for flamboyance, so he might have disappointed onlookers with his plain trilby and lightweight belted coat. But there was no disguising his elegant stature and remarkable good looks. The Prince had delicate facial features: slightly hooded eyes and a small mouth, frequently crimped at the corners in a brazen grin.

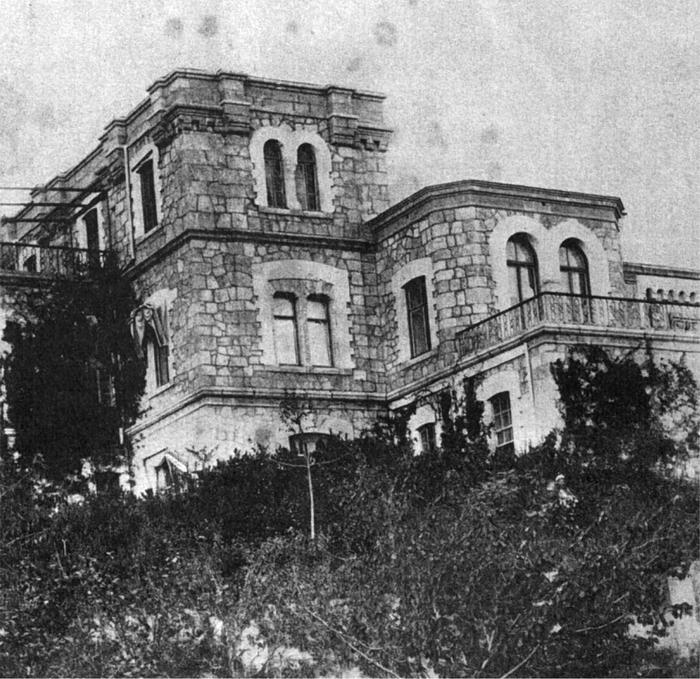

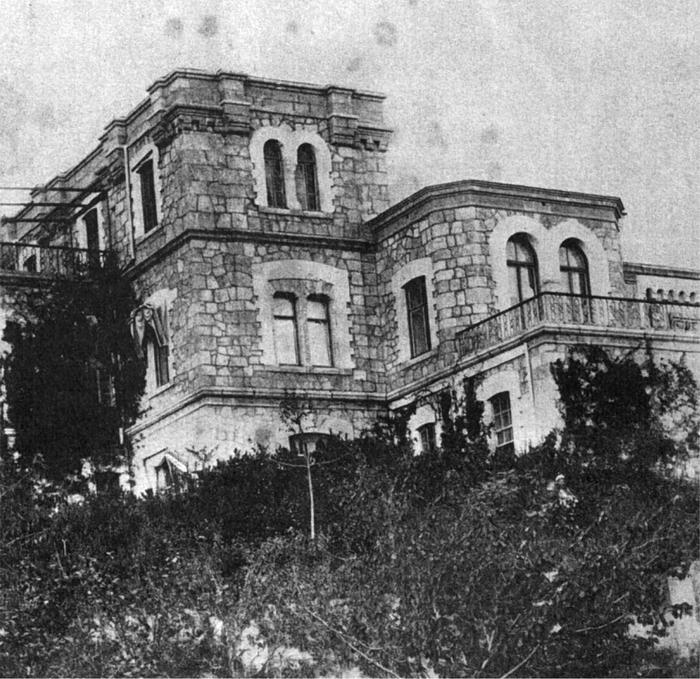

His father, meanwhile, the elder Prince Felix Youssoupov, had chosen to match the Grand Duke Nicholas in full, arresting Cossack military costume. While the elder Prince could not boast a distinguished war record, he was perhaps mindful of his position as owner of this particular mise en scne. The grandeur and savagery of his costume echoed the mood of the Koreiz estate, where sumptuous buildings pitted themselves against the encroaching Tartar wilderness. From its splendid terraces could occasionally be discerned the estate village, in which braying donkeys vied with the Moslem call to prayer.

The rough, winding road to the beach of Koreiz was now alive with motorcars and horse-drawn carriages. It is hard to know what each new arrival would have made of their first sight of the British battleship HMS Marlborough. The ship loomed majestically a little way offshore and all but the very youngest members of the party understood that they must embark within hours.

The Tsars 11-year-old nephew, Prince Vassily, often recalled his excitement as he contemplated travelling aboard a warship. But for many of the older members of the party, the sight could only serve to remind them that, while they finally knew by what means they would leave their homeland, they still had no fixed destination.

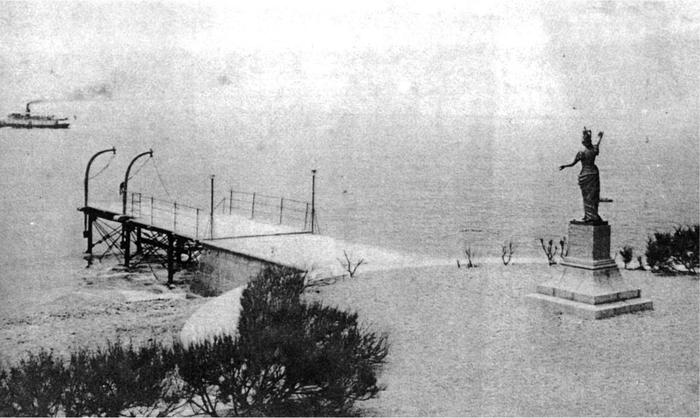

Some wistfully savoured what they feared would be their last views of the Tartar landscape. Their gaze would have been caught by the Youssoupovs statue of Minerva presiding over the jetty. They may also have ventured a final look at the bronze of Terzy, a mythical Tartar gypsy said to have thrown herself in the sea after being kidnapped by pirates. Others of the party were perhaps silently thanking God that, at last, they were leaving. They had suffered two turbulent years since the Revolution. Within the last nine months, 17 members of the Imperial Family had been murdered. On the night of July 16th/17th, 1918 the Tsar, Tsarina and their five children had been killed in Ekaterinburg. The following night, the Tsarinas sister had been buried alive, thrown down a mine with five other Romanovs.

The Koreiz estate house; and below, the statue of Minerva presiding over the jetty