INTRODUCTION

IN September, 1920, after staying three years in Siberia, I was able to return to Europe. My mind was still full of the poignant drama with which I had been closely associated, but I was also still deeply impressed by the wonderful serenity and flaming faith of those who had been its victims.

Cut off from communication with the rest of the world for many months, I was unfamiliar with recent publications on the subject of the Czar Nicholas II. and his family. I was not slow to discover that though some of these works revealed a painful anxiety for accuracy and their authors endeavoured to rely on serious records (although the information they gave was often erroneous or incomplete so far as the Imperial family was concerned), the majority of them were simply a tissue of absurdities and falsehoodsin other words, vulgar outpourings exploiting the most unworthy calumnies.

I was simply appalled to read some of them. But my indignation was far greater when I realised to my amazement that they had been accepted by the general public.

To rehabilitate the moral character of the Russian sovereigns was a dutya duty called for by honesty and justice. I decided at once to attempt the task.

What I am endeavouring to describe is the drama of a lifetime, a drama I (at first) suspected under the brilliant exterior of a magnificent Court, and then realised personally during our captivity when circumstances brought me into intimate contact with the sovereigns. The Ekaterinburg drama was, in fact, nothing but the fulfilment of a remorseless destiny, the climax of one of the most moving tragedies humanity has known. In the following pages I shall try to show its nature and to trace its melancholy stages.

There were few who suspected this secret sorrow, yet it was of vital importance from a historical point of view. The illness of the Czarevitch cast its shadow over the whole of the concluding period of the Czar Nicholas II.s reign and alone can explain it. Without appearing to be, it was one of the main causes of his fall, for it made possible the phenomenon of Rasputin and resulted in the fatal isolation of the sovereigns who lived in a world apart, wholly absorbed in a tragic anxiety which had to be concealed from all eyes.

In this book I have endeavoured to bring Nicholas II. and his family back to life. My aim is to be absolutely impartial and to preserve complete independence of mind in describing the events of which I have been an eyewitness. It may be that in my search for truth I have presented their political enemies with new weapons against them, but I greatly hope that this book will reveal them as they really were, for it was not the glamour of their Imperial dignity which drew me to them, but their nobility of mind and the wonderful moral grandeur they displayed through all their sufferings.

PIERRE GILLIARD.

To give some idea of what I mean, it is only necessary to record that in one of these books (which is based on the evidence of an eyewitness of the drama of Ekaterinburg, the authenticity of which is guaranteed) there is a description of my death! All the rest is on a par.

Everyone desiring information about the end of the reign of Nicholas II. should read the remarkable articles recently published in the Revue des Deux Mondes by M. Paleologue, the French Ambassador at Petrograd.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

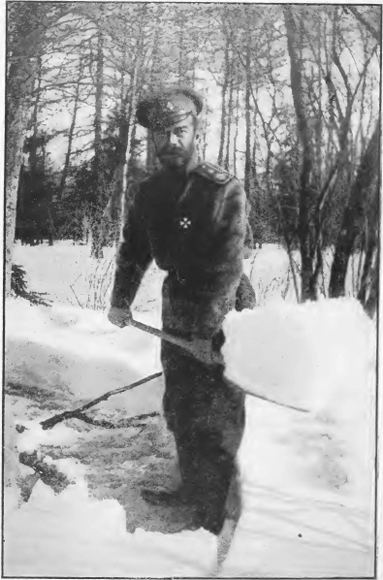

The Czar clearing snow at Tsarskoe-Selo

The Czarevitch in the park of Tsarskoe-Selo

The four Grand-Duchesses in 1909

The Czarina before her marriage

The Czarevitch at the age of fifteen months

The Grand-Duchesses Marie and Anastasie in theatrical costume

The Czarina at the Czarevitchs bedside

The four Grand-Duchesses gathering mushrooms

The Czarevitch cutting corn he had sown at Peterhof

Letter to the author from the Grand-Duchess Olga Nicolaevna, 1914

The Czarevitch with his dog Joy

The Czarina and the Czarevitch in the court of the palace at Livadia

The Czarina sewing in the Grand-Duchesses room

Excursion to the Red Rock on May 8th, 1914

The four Grand-Duchesses, 1914

The Czar and Czarevitch examining a captured German machine-gun, 1914

The Czar and Czarevitch before the barbed wire, 1915

The Czar

The Czarevitch

The Czarina

The four Grand-Duchesses

The Czar and Czarevitch on the banks of the Dnieper, 1916

The Czar and Czarevitch near Mohileff, 1916

The Czar and Czarevitch at a religious service at G.H.Q., Mohileff

The Grand-Duchesses visiting the family of a railway employee

The Czarina and Grand-Duchess Tatiana talking to refugees

The Grand-Duchess Marie as a convalescent

The four Grand-Duchesses in the park at Tsarskoe-Selo

The Czarinas room in the Alexander Palace

The Portrait Gallery

The Czar, his children and their companions in captivity working in the park

The Czar working in the kitchen-garden

The Czarina, in an invalid chair, working at some embroidery

The Grand-Duchess Tatiana carrying turf

The Czar and his servant Juravsky sawing the trunk of a tree

The Grand-Duchessses Tatiana and Anastasie taking a water-butt to the kitchen-garden

The Imperial familys suite at Tsarskoe-Selo, 1917

The Grand-Duchess Tatiana a prisoner in the park of Tsarskoe-Selo

Alexis Nicolaevitch joins the Grand-Duchess

The Czar and his children in captivity enjoying the sunshine at Tobolsk

The Governors house at Tobolsk, where the Imperial family were interned

The Czar sawing wood with the author

Alexis Nicolaevitch on the steps of the Governors house

The Imperial family at the main door of the Governors house

The Czarinas room

The priest celebrating Mass in the Governors house after the departure of Their Majesties

The river steamer Rouss on which the Czar and his family travelled

Ipatiefs house at Ekaterinburg, in which the Imperial family were interned and subsequently massacred

Yourovsky, from a photograph produced at the enquiry

The Grand-Duchesses room in Ipatiefs house

Ipatiefs house from the Vosnessensky street

The Czarinas favourite lucky charm, the Swastika

The room in Ipatiefs house in which the Imperial family and their companions were put to death

Mine-shaft where the ashes were thrown

The search in the mine-shaft