First published 1988

by Routledge

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1988 Routledge

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Mediterranean cities : historical perspectives

1. Mediterranean region. Port towns, history

I. Malkin, Irad, 1951 II. Hohlfelder, Robert L. III. Mediterranean historical review

909.09822

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mediterranean cities : historical perspectives / edited by I. Malkin and R.L. Hohlfelder.

p. cm.

This group of studies first appeared in a special issue on Mediterranean cities: Historical perspectives of Mediterranean historical review, vol. 3, no. 1. T.p. verso.

1. HarborsMediterranean RegionHistory. I. Malkin, Irad. II. Hohlfelder, Robert L. III. Mediterranean historical review.

HE557.A3M43 1988

387.1091822dc19

ISBN 13: 978-0-714-63353-4 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-138-98080-8 (pbk)

This group of studies first appeared in a Special Issue on Mediterranean Cities: Historical Perspectives of Mediterranean Historical Review, Vol.3, No.1.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of Routledge.

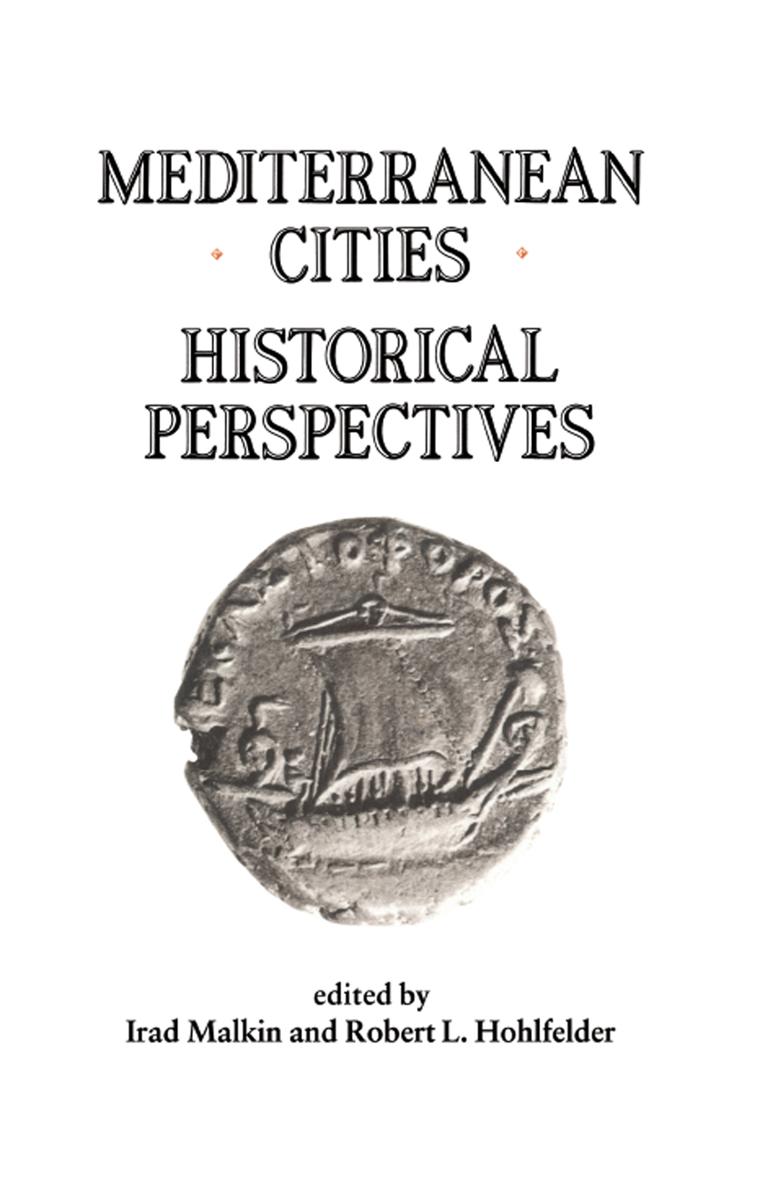

Cover photograph: Roman coin from the time of Nero, showing a merchantman facing right, probably a Roman grain ship which transported grain from Egypt to Rome. Billon, 23mm., minted at Alexandria. (Courtesy of the National Maritime Museum, Haifa)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original may be apparent

The Mediterranean provides the context for all the cities which appear in this volume: all are (or have been) port cities, and as such their harbours played a significant role in shaping their histories. In essence, the question of interaction between man and sea is one of the influence of the maritime position on the human communities constituting the Mediterranean cities: the connections between them, and the link of each city with its hinterland, as well as the influence of its position on the citys internal development and character.

Among all the fruitful Mediterranean discussions which emanated from the works of Braudel and Goitein, for example, one also encounters some distorted perspectives. In a modern world, where the importance of the Mediterranean has declined, certain contemporary scholars nostalgically turning to the past, seem to compensate for the decline by according this sea a kind of divine status, as to a dead Roman emperor. In their works the Mediterranean begins to play an almost self-conscious role in determining human history. On the other hand, the reaction of the strictly anthropocentric historians, which is sometimes not unjustified, runs the danger of forgetting all about that extra-human reality (or that over-used word environment) which does influence the human story. So, at the beginning of this volume, a call for a sense of proportion is due: without unnecessary exaggeration, the self-evident role of the sea in a port city is acknowledged; moreover, the Mediterranean in particular, especially up to the early modern period, does have a history, although not always a unified one. The historian has no need of a Roman mare nostrum in order to treat the Mediterranean area as a legitimate subject.

Our purpose is not to uncover the underlying patterns of the Braudelian longue dure; the approach here is more nominalistic. It is hoped that the study of a number of port cities Byzantium, Caesarea, Genoa, Amalfi, et cetera may yield some wider implications. For example, cities like Caesarea Maritima or Amalfi seem to illustrate that natural conditions were not necessarily the overriding determinant factor for the Mediterranean port city. Both are quite poor in terms of their harbour, and their significance as port cities lies rather in social and political causes. As Barbara Kreutz aptly reminds us, only comparatively recently has western civilization come to enjoy the luxury of geographical determinism.

The question of the significance of harbour construction in antiquity is discussed by D.J. Blackman. A fresh look is introduced regarding questions which necessarily arise since the influential study of Lehmann-Hartleben (1923). For example: did methods of harbour construction progress evenly and universally, as Lehmann-Hartleben thought, or does the distinction between large and small harbours imply different needs or historical contexts? Are the smaller harbours, especially those built with primitive techniques, necessarily the earlier ones? What does the large number of small harbours in the ancient world, often with specialized functions, signify? How quickly did technical knowledge spread across the Mediterranean? Did harbour construction in itself add an impetus to interconnections? By whom, and how, were harbour construction and operation administered and financed? Finally, throughout his paper, Blackman addresses the question of the new synthesis which may be culled from the progress of harbour archaeology in the Mediterranean. Focusing not only on the more prominent remains but also on bollards enriches the picture.

New light is often shed on a historical problem as a result of a fresh connection between known facts. This is all the more interesting in the case of problems which even in antiquity were considered riddles. Colonized by Greek Megara, Byzantium, with its superb harbour, was to enjoy a celebrated future. But the site of Byzantium, whose natural advantages are self-evident, was bypassed by the same mother-city in favour of the site opposite (Chalkedon), when it first came to settle the furthest point of the Propontis. Through an analysis of sailing conditions in the Hellespont and the Propontis together with the ancient evidence, I. Malkin and N. Shmueli suggest a new answer which seems to explain why Chalkedon was settled before Byzantium. The inclusion of Byzantium in a volume on Mediterranean cities is justified by the fact that in terms of the ancient Mediterranean