First published 2005 by Pearson Education Limited

Published 2014 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2005, Taylor & Francis.

The right of Owen Davies to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notices

Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary.

Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility.

To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the authors, contributors, or editors, assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions, or ideas contained in the material herein.

ISBN 13: 978-0-582-89413-6 (pbk)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book can be obtained from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

A CIP catalog record for this book can be obtained from the Library of Congress

Set by 3

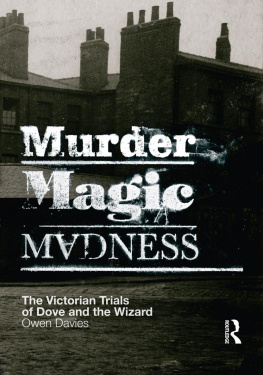

T his book is not a whodunnit. William Dove killed his wife. Nevertheless at the heart of this book is a mystery. What led the scion of a prosperous and widely respected Methodist family to commit murder? Yet it was not this question that first attracted me to the case. It was Doves curious involvement with a wizard named Henry Harrison that caught my attention. Much of my work has been dedicated to demonstrating the continued relevance and social importance of magic in nineteenth-century England, and this seemed, at first, to be just another example to prove my point. Once I began to research the backgrounds of Dove and the wizard, however, it became clear that their respective life histories, and the consequences of their relationship, provided an extraordinary insight into many more facets of mid-Victorian society. Indeed, when deciding on the title for this book I kept juggling with alliterative nouns. I decided on murder, magic, madness but it could just as appropriately have been Methodism, medicine and marriage.

There is nothing new in the use of a murder case as a window on to the social and cultural milieu in which it was committed. Few subjects are better at luring people into studying the past than true crime. The murderer, as Angus McLaren has put it, can act as a grim guide through the society of the time. McLaren examined the case of the late nineteenth-century serial killer Thomas Neill Cream to provide insights into the cultural role of the medical man, the development of police procedure and perceptions of female sexuality. Others have successfully used the trial in 1857 of the poisoner Madeleine Smith as a means of exploring Victorian newspaper reportage, middle-class society and Scottish jurisprudence. The trial of another poisoner, William Palmer, who plays no small part in this book, has proved a fascinating means of exploring the contentious role of expert medical witnesses in Victorian courts.1 For an example of how a murder case can illuminate the world of popular beliefs, particularly with regard to magic and witchcraft, we can turn to two books on the sensational Irish trial of Michael Cleary who, in 1895, with the help of other family members, burned his wife to death believing she was a fairy changeling.2 Jack the Ripper, of course, dominates the popular discourse on Victorian crime. The legion of populist books and films on the subject concentrate on unmasking the identity of the misogynistic serial killer, but the academic focus has been on what the press reports of the murders tell us about middle-class conceptions of morality and sexuality.3

This book is not, though, just about the act of murder and its cultural significance. It is also a work of biography, an attempt to show how two individuals lives were shaped, categorised and condemned by a complex web of social, cultural, religious, intellectual and legal forces. Biography is a strong aspect of history publishing. Indeed, look at the history section of any high street bookshop or the book review pages of any broadsheet and you will find its disproportionate presence. This is quite understandable, but if there is a problem with biography as history, it is that the lives recounted and examined are usually those of the rich, famous or influential. It is rare, indeed, to read the life stories of the humble labourer, artisan or farmer. Of course, we have fine biographies of those of lowly birth, such as the poet John Clare and Charles Dickens, who rose to fame through their literary or artistic talent.4 Historians are also fortunate to have the autobiographies of the autodidactic, politically conscious working classes, and also the religiously inspired, particularly the Methodists, who often desired to have their spiritual journeys recorded in memoirs. The latter have proved particularly valuable for reconstructing William Doves early life.5 What historians rarely do, though, is focus on the biographies of the ordinary, or even the ordinary whose lives may have been briefly illuminated by fleeting notoriety. The reason is primarily, but not solely, to do with the paucity of sources. Without diaries or artistic works to interpret, you cannot get very far with the basic facts provided by parish records and censuses. When the sources are sufficient to build up the life histories of the illiterate, the poor, or people like Harrison, who left no personal record of their lives, it is often only because they have committed a serious crime. From the mid-nineteenth century, in particular, with the growing importance of defence counsels in major trials, the biography of the accused became an integral aspect of both prosecution and defence cases.

In the case of Dove and Harrison, however, nearly all the relevant court records are lost. The assize depositions are missing from the boxes where they should be in the Public Record Office, and there are no surviving Leeds coroners papers for the period. This may seem to be a serious setback in reconstructing events but it is not thanks to newspapers. The court records would certainly have been helpful in confirming specific details but they rarely provide information not reported by the sensation-hungry press. In fact, newspaper reports of prosecutions often provide far greater detail because they covered the actual trials. Evidence given by witnesses under cross-examination can provide many more details about events leading up to a crime, and about the behaviour and relationships of the individuals concerned, than those gleaned from depositions. Court reports also provide us with information about the physical characteristics of defendants, witnesses, judges, jurors and lawyers. But newspapers were not only essential to this book as a source material. As an increasingly powerful cultural force at the time, they also profoundly shaped the development of the relationship between Dove and the wizard, and ultimately their fate.