This eBook edition published in 2014 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

First published as The Mirror of Monte Cavallara, Birlinn 2006

Copyright the Estate of Ray Ward 2014

Foreword copyright Trevor Royle 2014

Afterword copyright Robin Ward 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise without the express written permission of the publisher.

eBook ISBN: 9780857908148

ISBN: 9781843410669

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

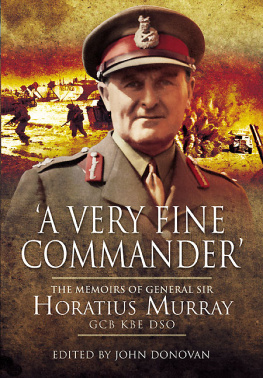

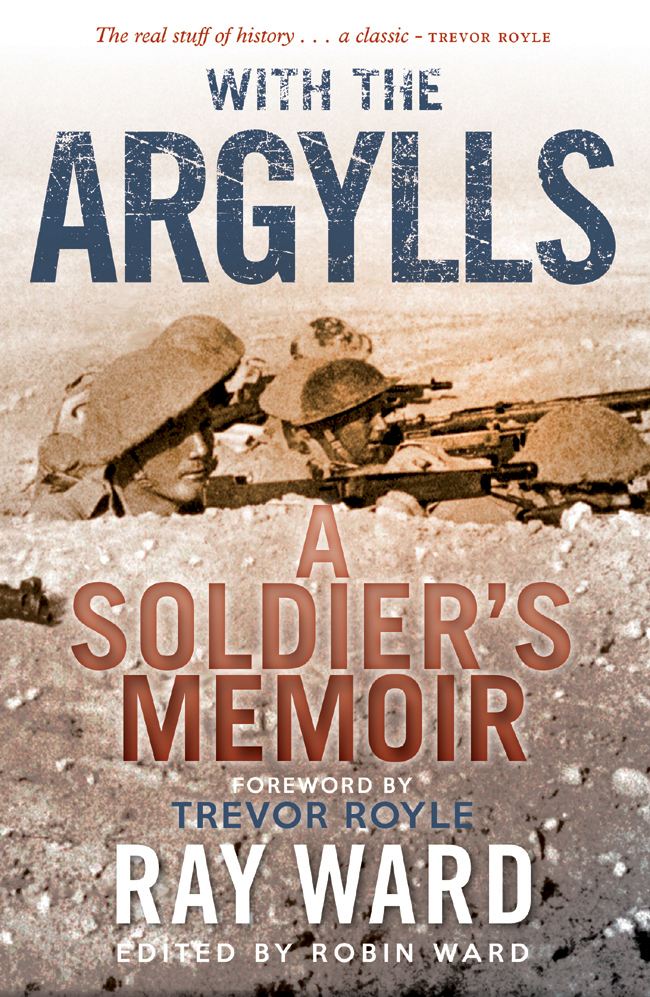

Foreword

To gain some understanding of what a soldier feels like before going into battle it is only necessary to read Ray Wards account of an action in Italy in October 1944 which saw British infantrymen attacking a heavily defended German position on Monte Cavallara. At the time he was commanding a rifle company in 1st Battalion The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders during the long and frequently bitter assault which took the Allied armies up through Italy towards the Gothic Line, the formidable German redoubt which ran from La Spezia in the west to Pesaro in the east and which made good use of the unbroken line of the Apennine mountain range. The task fell to A Company and the orders received by Ward were unambiguous. It was vital, said the commanding officer, that the position be taken at all costs. In other words the men of the Argylls had to press home their attack regardless of casualties and that is precisely what they did. At dawn on 7 October 1944 the attack went in as planned but all too soon A Company was in trouble as it ran into sustained German machine-gun and mortar fire. Reinforcements arrived in the shape of B Company and eventually the position was captured but at some cost. All told, the Argylls lost 15 men killed and 44 wounded30 percent casualties. Later, Ward reflected that it had not been a big show, just a routine attack with a limited objective; wishful thinking by the brass to seek a breakthrough then in that part of the line.

In the wider history of the Italian campaign Monte Cavallara was probably little more than a footnote but at the time it was a sobering reminder of the price which must be paid by a thin screen of infantry ordered to attack a heavily defended position to prevent the wider advance stalling. However, behind that bleak arithmetic of war Ward tells another story describing the kind of men who went into the attack and delineating their hopes and fears. It soon becomes clear that it was not all derring-do and happy warriors. Amongst his three platoon commanders was a newly arrived subaltern who admitted his fears and thought he would not survive the battle, thereby breaking a taboo amongst men in the front line. Sadly, it turned out to be a self-fulfilling prophecy. Another officer died in agony, his mangled guts spilling out on the ground as Ward tried to comfort him with a tot of rum. During the fighting a reluctant sergeant could not hide his relief when a bullet hit him in the foot, thereby providing him with a legitimate passport out of battle. Then, in the second wave Ward witnessed his fellow company commander kicking some of his men who had seen the killing power of the German spandau machine-guns and were not exactly keen to go over the top. None of this is related in a critical way but it is telling. By that stage of the war Ward was an experienced soldier who had seen sights no humans should be permitted to see and his words are a reminder that in the hellish fear of battle men sometimes forget to die like heroes. It is small wonder that his sons remember that their father was plagued by flashbacks and nightmares from that period in his life, probably suffering from what we now know to be post-traumatic stress disorder.

In that sense, these memoirs bear witness to a conflict which has become almost unimaginable for later generations. Written in retirement and based on his wartime diaries Wards reminiscences are at once candid, revealing and deeply human; they are the real stuff of history. They give a wonderful insight into the impulses that drove young men in 1939 and 1940 to address the unfinished business of the earlier global conflict. Thomas Raymond Ward was far from being an unwilling conscript and during his basic infantry training he emerged not only as a natural soldier but at an early stage showed that he was officer material: the encomium came from a prewar regular sergeant with experience of service in China and Indias North-west Frontiera good judge. Posted to an Officer Cadet Training Unit, Ward continued to make good progress as the large and frequently unwieldy wartime army began to take shape.

In many respects it was the nation in uniform, a huge melting pot in which youngsters came from every kind of background, having been thrown together to do their bit for king and country. In general they were malleable and reasonably willing soldiers. Most did not fight for well-defined abstracts such as duty and honour although it was not difficult to uncover a deep seated and genuine belief that Nazism was evil and had to be crushed. Above all, a quest for adventure played a part and it was never far away from Wards mind especially when he found that his battalion was bound for service in North Africa. At a time when the majority of the British population did not have access to foreign travel and cheap package holidays belonged to the distant future the chance to travel was a huge spur and one which most recruits embraced even though service overseas brought with it the possibility of seeing action. After all these were young men who believed that death happened to other people and that with luck they would emerge from the fighting unscathed.

Added to that heady optimism which has always encouraged young men to place themselves in danger there was also the certain knowledge that for most of them the war was finite, that they had signed up for the duration and that there had to be something better in store once the guns had finally fallen silent. In no other episode is this belief more tellingly exposed than in Wards observation about the treatment of soldiers aboard the troopship taking them to Egypt by way of the long route around South Africa. Whereas the officers enjoyed peacetime standards of cruise ship comfort, the soldiers occupied cramped and fetid quarters below decks. While this did not turn Ward into a socialist overnight he remained convinced that treatment of that kind must have influenced returning servicemen to vote Labour in the first postwar General Election in the summer of 1945.

Once in North Africa the 1st Argylls became part of the Eighth Army, the great desert force which defeated the German and Italian armies in 1942 and in so doing gave the first signs of hope that the war could be won. In common with other soldiers who served in North Africa Ward was enormously impressed by the wild beauty of his surroundings which had few comparisons with any other theatre of the Second World War. At first acquaintance the North African terrain was harsh, barren and inhospitable, but it was also strangely compelling, a landscape which imprinted itself on the minds of the men who fought there. In fact, very few failed to be affected by the sheer size of the desert arena over which the two opposing armies fought and noted with approval its absence of definition and the seemingly limitless horizons with few roads or tracks to break up the bare expanse of sand and scrub. Responding to its similarities with a classical sporting arena, war correspondents on both sides tended to report the conflict using an imagery which spoke of a courtly tournament involving valiant rivals and chivalrous generals. Ward, too, seems to have been similarly enraptured and his response was probably influenced by the fact that part of his service in the desert saw his platoon acting as headquarters bodyguard to the eccentric but gifted General Bernard Law Montgomery who was admired by his men because he was obviously a winner yet was cautious of their lives.