Red Kestrel Books 2019, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

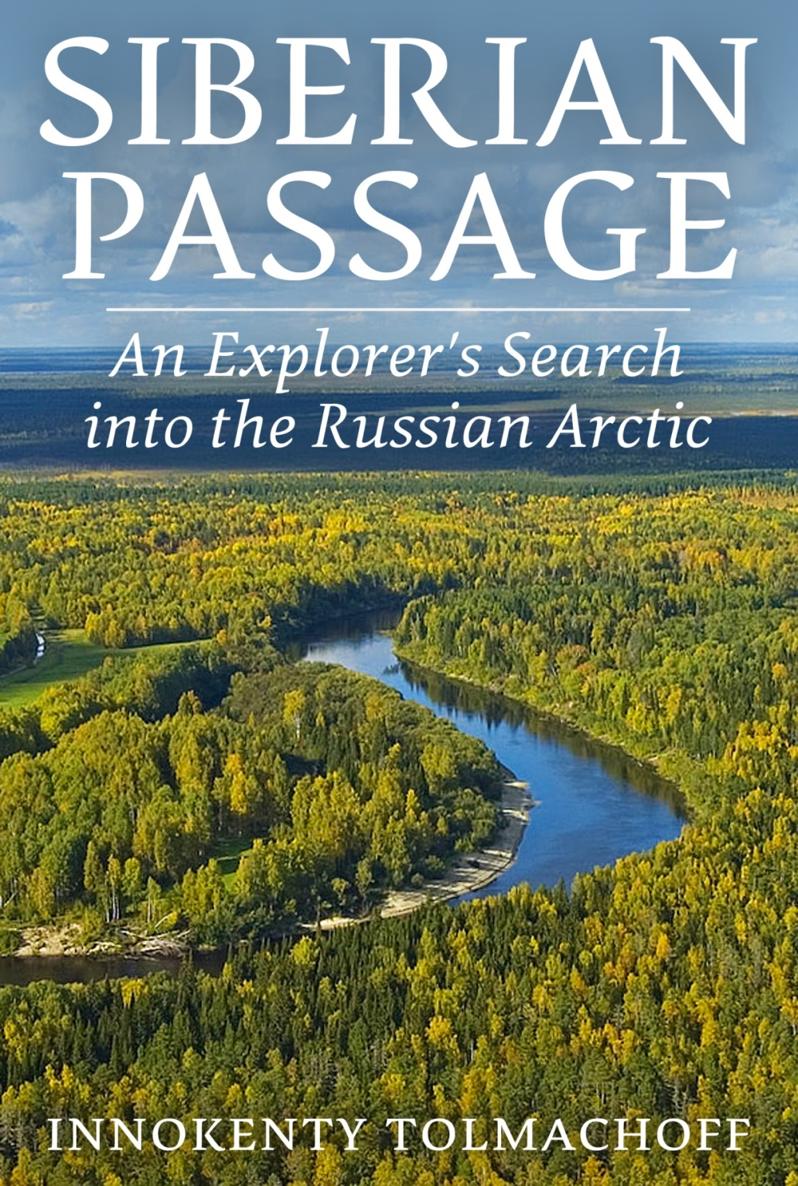

SIBERIAN PASSAGE

An Explorers Search into the Russian Arctic

INNOKENTY P. TOLMACHOFF

Siberian Passage was originally published in 1949 by Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, New Jersey.

1 INTRODUCTION

ALTHOUGH the expedition which is described in this book took place forty years ago, nothing has been published on its work except a few preliminary official reports and technical papers in Russian. A detailed description in Russian was being prepared for publication when, in 1914, World War I broke out, and work with the Red Cross brought my scientific activities to an abrupt end. During the Russian Revolution and immediately thereafter, I was more concerned with political, social, and economic work than with the preparation for publication of a report on the expedition. My departure from Russia which followed in 1922 again delayed such activity.

At the present time the expedition has been apparently forgotten in Russia, and outside of Russia it was never well known. The events of the expedition are told in this book exactly as they happened and should be considered in the light of historical perspective. I have not attempted to bring up to date my account of the life of that part of Siberia through which I traveled, or of the political and economic position of the Russian and native populations. I lack the data which would permit me to make a correct judgment on the changes which have occurred, and I am rather doubtful whether it would be possible to secure a complete or unbiased record from contemporary Russia.

From the reports of present-day travelers through parts of Yakutsk Province, however, there is some indication of how life there now compares with that of the time of the expedition. Conditions of travel, these visitors find, are not very different from those existing forty years ago. In spite of the fact that Yakutsk Province, now known as Yakutya, has become an independent unit in the U.S.S. R., orders from Moscow are as important there today as those formerly issued from St. Petersburg. Governor, Ispravnik, Zasyedatel, and other former officials have been replaced by the president of the Yakutya and the different Soviet commissars. Soviets function in town and village, but the political and economic status quo of the population evidently does not differ much from that of former years. Automobiles run regularly between Irkutsk and the upper Lena River, but in a greater part of the region horses, reindeer, and dogs are still the only means of transportation. The same work is necessary to prepare means of transportation for an expedition, and the same mistakes and negligence of the local administration are possible after forty years. Although the whole administrative machine has changed its structure and appearance, it has been impossible to change the habits of nomads dependent for their life upon their reindeer, or of Yakuts still living under the same roof with their cows. Securing horses among them still requires special messengers, long journeys, and meetings of local Soviets.

Unlike the inhabitants of Yakutsk Province, the Chukchi have seen important changes in their political and economic position. The Soviet succeeded where the old Russian government failed. Chukchi have lost their former independence and are now at the same level as other Siberian natives in their political relation to Russia. Many of the changes may be traced to the greater development of sea communication through Bering Strait in the post-war period, and to the growing use of aircraft. No part of the country is now so isolated as it was before., Undoubtedly recent visitors to the Chukchi Peninsula do not feel as if they were traveling in a foreign country among people for whom orders of the Central Russian government or its local agents have no meaning.

Material culture has not changed so much. The Chukchi still live in their yerangas and pologs, as they have for generations. Reindeer Chukchi still depend on their herds. The Maritime Chukchi of today still depend chiefly on hunting sea animals, and their successful years alternate with lean ones which bring them close to starvation. In general, conditions of the Maritime Chukchi have undergone a more favorable alteration than those of the Reindeer Chukchi. By Soviet edict the former have stopped trading with Americans. They no longer have their American rifles and have been forced, therefore, to return to the old art of hunting with bow and spears, the use of which prehistoric instruments was almost forgotten. Even in the best trained hands, such weapons cannot compete with an American Winchester.

The character of the native Siberian has undergone very little change as a result of the Revolution. If this expedition were to be undertaken today, and an account of it written, the story would be similar to this record of a journey made forty years ago. Certain aspects of Russias old regime reflected in this book color the story but do not affect its essential elements.

2 ORGANIZING THE EXPEDITION

ONE AFTERNOON in the autumn of 1908 the telephone rang in my office at the Geological Museum of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg. The call was from General Vilkitzki, Chief of the Russian Hydrographical Survey, and a good friend of mine.

Come to my office at once, if you can. We have some very important business here, he said without introduction or explanation.

A few minutes later I was at the old Admiralty Building. In Vilkitzkis office I found his assistant, General Drijenco; the president of the Russian Geographical Society, General Shocalski; and the governor of the Yakutsk Province, Mr. Kraft, in whose plan, unfolded at this meeting, I was to be involved for more than a year.

Governor Kraft told me that he was very much concerned about the development of the northern part of his province and particularly interested in the utilization of the northern sea route for the benefit of that really desolate section of the country. The possibility of commercial navigation along the Arctic coast of Siberia west of Bering Strait was still a matter of speculation, and further investigation and study would have to be made before a final decision one way or another could be reached. If navigation was worthwhile from an economic standpoint, it would require the organization of certain shore services, the building of navigation signs, and coal depots. Auxiliary stations would be needed where, in the event of wrecks, crews could find provisions and medicaments, and could establish communication with the interior of the country. It was also true that navigation along the northeastern coast would be helped very much if conditions of ice could be observed at special shore stations and reported to passing ships.