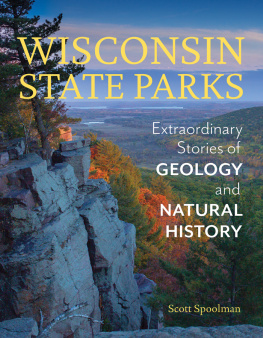

STUDYING WISCONSIN

STUDYING WISCONSIN

The Life of Increase Lapham

early chronicler of plants, rocks, rivers, mounds and all things Wisconsin

Martha Bergland and Paul G. Hayes

WISCONSIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY PRESS

Published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Publishers since 1855

2014 by Martha Bergland and Paul G. Hayes

E-book edition 2014

Publication of this book was made possible in part by a gift from the

D. C. Everest fellowship fund.

For permission to reuse material from Studying Wisconsin

(ISBN 978-0-87020-648-1, e-book ISBN 978-0-87020-649-8),

please access www.copyright.com or contact the

Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923,

978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration

for a variety of users.

wisconsin history .org

Photographs identified with WHi or WHS are from the Societys collections;

address requests to reproduce these photos to the

Visual Materials Archivist at the Wisconsin Historical Society,

816 State Street, Madison, WI 53706.

Front cover: WHi Image ID 1944, Increase Lapham inspecting a piece of the Trenton meteorite.

18 17 16 15 14 1 2 3 4 5

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Bergland, Martha, 1945

Studying wisconsin : the life of Increase Lapham, early chronicler of plants, rocks, rivers, mounds and all things Wisconsin / Martha Bergland and Paul G. Hayes.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-87020-648-1 (hardback) ISBN 978-0-87020-649-8 (ebook) 1. Lapham,

Increase Allen, 1811-1875. 2. Natural historyWisconsin. 3. BotanistsWisconsin

Biography. 4. NaturalistsWisconsinBiography. I. Hayes, Paul G. II. Title.

QK31.L3B47 2014

580.92dc23

[B]

2013036967

To the memory of my husband, Larry Barnett, who called him Decrease

M. B.

To my wife Philia, who patiently shared our home with Increase Lapham for more years than this book was in writing

P. H.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

INCREASE ALLEN LAPHAM, ONE OF THIRTEEN CHILDREN of a New York Quaker family and a self-taught all-around scientist whose curiosity led him into many fields, made his home in Wisconsin from age twenty-five in 1836 until his death in 1875. In that time, he worked as an engineer, surveyor, land agent, cartographer, botanist, geologist, meteorologist, archaeologist, limnologist, and zoologist. A published scientisthis first paper appeared in the American Journal of Science and Arts when he was sixteenhe wrote Wisconsins first scientific paper, a list of plants and shells found in Milwaukee, the year he arrived. In 1844, before Wisconsin became a state, he finished the first book published in Wisconsin, a geography that he hoped would attract immigrants to the territory. He promoted education and culture, being a founder of the Milwaukee Lyceum; the Milwaukee Young Mens Association; the Milwaukee Female Seminary; the Wisconsin Historical Society; and the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters; and he was in on the beginnings of the Milwaukee Public Library and the Milwaukee Public Museum.

In his prime, he surveyed, drew, and described the Indian effigy mounds that distinguished Wisconsins landscape in a book for the Smithsonian Institution in 1855The Antiquities of Wisconsin, his most famous work. In 1869, he warned of the disastrous effects of the destruction of forest trees now going on so rapidly in the State of Wisconsin in a prescient report to the state regarding the great cutover of the northern pinery, an example of conservation writing that predated by decades the beginnings of the National Forest Service. His concern over the loss of sailors, vessels, and cargo in Great Lakes storms was a major factor leading to the creation of the US Weather Bureau and as its early employee he wrote the nations first official weather forecast. Late in life, he was appointed Wisconsin state geologist and he presided over the organization of the Wisconsin Geological Survey.

Today the University of WisconsinMilwaukee teaches natural science in Lapham Hall. Lapham Peak dominates the Kettle Moraine formation in Waukesha County. Madison youngsters attend Lapham Elementary School. Lapham Streets carry traffic in Oconomowoc and Milwaukee. The Wisconsin Archeological Society awards its Increase A. Lapham Research Medal to scientists who make important contributions to that science. A fossil trilobite, a plant genus, and distinctive markings in metallic meteorites all have been named for Lapham. Formal portraits of Lapham are prominent at the Wisconsin Historical Society and in a mural in the Wisconsin State Capitol building. A bronze bust of Lapham can be found at the Milwaukee Public Museum.

Increase Lapham may have been Wisconsins most-respected, most-honored citizen of his time. Yet for almost 140 years after his death, no full biography of Wisconsins pioneer scientist, educator, and scholar has been published. Graham P. Hawks finished an unpublished biography of Lapham in 1960 as his doctoral thesis in history at the University of WisconsinMadison. Partial biographies have appeared as articles, perhaps the best of them by Newton H. Winchell, professor of geology at the University of Minnesota and editor of The American Geologist, in which his tribute to Lapham appeared in January 1894. Milo M. Quaife, superintendent of the Wisconsin Historical Society and founder of the Wisconsin Magazine of History, ran his Increase Allen Lapham, Wisconsins First Scholar as the first article in the first issue of the magazine in September 1917. Other articles through the years examined specific Lapham contributions: Lapham the pioneer patron of Wisconsin education; Lapham the mapmaker; Lapham the meteorologist and a founder of the US Weather Bureau; Lapham the geologist, the botanist, the agriculturalist, the author, the archaeologist, the surveyor and canal engineer, the promoter of scholarly institutions.

Among the reasons no biography was written may have been the prodigious amount of original Lapham material that was left behind. Shy and modest in person, Lapham was a prolific letter writer, note-taker, data-gatherer, compiler of lists of species, and writer of essays, geographies, scientific articles, and histories. He preserved his original, handwritten manuscripts and copies of letters, even scraps of notes. He wrote frequently about Wisconsin for local newspapers and he clipped articles of scientific or geographic interest, pasting them into scrapbooks. Modest as he was he seemed intent on leaving behind all that he had learned about Wisconsin and science, not so much for personal glory but because he believed the information was valuable. After his death, his daughter Julia A. Lapham assumed the curatorial role. She organized his papers and selectively transcribed much of his correspondence, diaries, and journals into hundreds of typed pages, all of which went to the Wisconsin Historical Society before her death in 1921. The Lapham collection at the Society fills twenty-seven boxes, including Julia Laphams transcriptions.

Next page