Annie Cohen-Solal - Picasso the Foreigner: An Artist in France, 1900-1973

Here you can read online Annie Cohen-Solal - Picasso the Foreigner: An Artist in France, 1900-1973 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New York, year: 2023, publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, genre: Non-fiction / History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Picasso the Foreigner: An Artist in France, 1900-1973

- Author:

- Publisher:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Genre:

- Year:2023

- City:New York

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Picasso the Foreigner: An Artist in France, 1900-1973: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Picasso the Foreigner: An Artist in France, 1900-1973" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Absorbing [and] astute . . . Cohen-Solal captures a facet of Picassos character long overlooked. Hamilton Cain, The Wall Street Journal

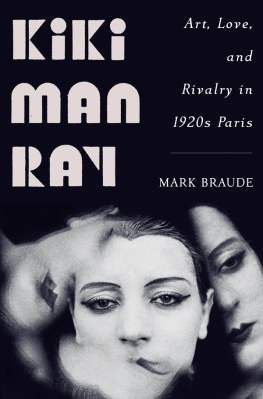

A beguiling read, as ingenious as it is ambitious . . . See Picasso and Paris shimmering with new light. Mark Braude, author of Kiki Man Ray: Art, Love, and Rivalry in 1920s Paris

Born from her probing inquiry into Picassos odyssey in France, which inspired a museum exhibition of the same name, historian Annie-Cohen Solals Picasso the Foreigner presents a bold new understanding of the artists career and his relationship with the country he called home.

Winner of the 2021 Prix Femina Essai

Before Picasso became Picassothe iconic artist now celebrated as one of Frances leading figureshe was constantly surveilled by the police. Amidst political tensions in the spring of 1901, he was flagged as an anarchist by the security servicesthe first of many entries in what would become an extensive case file. Though he soon became the leader of the cubist avant-garde, and became increasingly wealthy as his reputation grew worldwide, Picassos art was largely excluded from public collections in France for the next four decades. The genius who conceived Guernica as a visceral statement against fascism in 1937 was even denied French citizenship three years later, on the eve of the Nazi occupation. In a country where the police and the conservative Acadmie des Beaux-Arts represented two major pillars of the establishment at the time, Picasso faced a triple stigmaas a foreigner, a political radical, and an avant-garde artist.

Picasso the Foreigner approaches the artists career and work from an entirely new angle, making extensive use of fascinating and long-understudied archival sources. In this groundbreaking narrative, Picasso emerges as an artist ahead of his time not only aesthetically but politically, one who ignored national modes in favor of contemporary cosmopolitan forms. Cohen-Solal reveals how, in a period encompassing the brutality of World War I, the Nazi occupation, and Cold War rivalries, Picasso strategized and fought to preserve his agency, eventually leaving Paris for good in 1955. He chose the south over the north, the provinces over the capital, and craftspeople over academicians, while simultaneously achieving widespread fame. The artist never became a citizen of France, yet he enriched and dynamized its culture like few other figures in the countrys history. This book, for the first time, explains how.

Includes color images

Annie Cohen-Solal: author's other books

Who wrote Picasso the Foreigner: An Artist in France, 1900-1973? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.