by H.R.H. The Duke of Edinburgh K.G., K.T.

The story of Julius and Harold Wernher is played out during an exceptionally dramatic period in history. Julius became a leading figure in the European infiltration of Africa and with the rapid development of its very rich resources. As a young army officer, Harold lived through the horrors of the trench warfare in France before he was able to enjoy some of the fruits of his fathers financial genius. He then started a successful business career on his own account before being caught up in the higher levels of management of the war effort in the Second World War. He lived on to witness the social, political and industrial upheaval in Europe which followed the havoc of devastating wars and revolutions.

It is now fifty years since the end of the Second World War and there have been some ups and downs, but nothing to compare with the collapse of the nineteenth-century world during the first fifty years of this century. This book follows the events in the lives of two particularly able and enterprising men and the domestic and social fluctuations in the fortunes of their families and friends. It would have been an interesting story of human triumph and disaster in any epoch, but what gives it a special fascination is the cataclysmic scenario in which this group of people had to live out their lives.

The idea for this book arose when descendants of Sir Harold Wernher decided that the record must be put straight about his role in the Mulberry project, the artificial harbour which had been so crucial to the success of the Normandy landings in June 1944. The family was shocked that he should continue to be unjustly misrepresented by some modern writers. I was intrigued by the possibility of such a book, having recently visited Arromanches and seen the remains of that extraordinary structure, still there after over forty-five years.

There is still no satisfactory complete history of Mulberry. But I knew already that Mountbatten had appointed Sir Harold, a tough and brilliant businessman with a fine record in the First World War, to be his Chief Co-ordinator in Combined Operations , with access to all Cabinet Ministers and Service planners. This had developed into a huge and important job not least of the problems being the successful maintenance of secrecy. Mountbatten , I discovered, had also been appalled by the lack of recognition for Harold when the war was over. From private papers and documents it became clear that Harold had made too many enemies, especially at the War Office; for he was the sort of man to whom the tag did not suffer fools gladly is inevitably applied, and he found himself faced with a barrier of bureaucracy and jealousies. He had of course been hurt at being overlooked in official citations. Yet in spite of seeming thick-skinned to some observers, he was also to a certain degree modest and never wanted to advertise what must have rankled as a deep grievance.

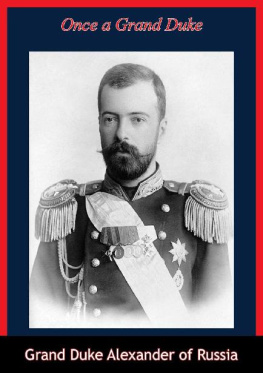

Even a brief study of Sir Harolds life led me inevitably to his father, Sir Julius Wernher, the most powerful of all the Randlords from South Africa, immensely wealthy and a great philanthropist . And neither of these could be separated from their wives, both of them strong characters in their own right: Sir Juliuss wife Alice, who later became Lady Ludlow, and Sir Harolds wife Lady Zia, daughter of Grand Duke Michael of Russia. Thus, within the limits of space available, I have expanded my theme to include both generations. I had twice visited the Collection at the Wernhers mansion, Luton Hoo, with its grand Belle Epoque interior and semi-Palladian exterior, and had admired Lady Zias famous Faberg and the Russian Rooms. Thus I was already aware of her Tsarist background and her descent from the poet Alexander Pushkin. In the racing world Zia had become a household name, and at Luton Hoo I saw the many trophies connected with the Wernhers celebrated racehorses, notably Brown Jack, considered to be one of the greatest horses in racing history, Meld and Charlottown, the Derby winner. I also had been amazed by the richness and variety of the Collection , with its medieval ivories, Renaissance jewellery and bronzes, Limoges enamels, majolica, tapestries, English porcelain, and paintings by Rubens, Titian, Reynolds and Bermejo. Some of the furniture, silver and other objects, including most of the Dutch paintings, had been acquired by Harold, but the main Collection had been formed by Sir Julius Wernher, reputedly so busy that dealers would have to visit him at breakfast. The English porcelain had been the contribution of Juliuss wife, and is regarded as the most important after the royal and the Victoria and Albert collections.

Sir Julius had first made his fortune out of diamonds at Kimberley, which resulted in his becoming a Life-Governor of De Beers. The goldmining companies that he came to control at Johannesburg were collectively known as the Corner House, a symbol throughout the financial world at the time for immense prosperity and rectitude. I certainly was not intending to write a business history, but, as in the case of Harold and Mulberry, I was chiefly interested in his character within the context of his business interests. Geoffrey Wheatcroft in TheRandlords remarked that there had never been a biography of Julius, and only an early and unsatisfactory one of his close partner, Alfred Beit, much more then in the public eye, and whom Wheatcroft considered the greatest genius of the first generation of magnates. In his book about the Corner House A. P. Cartwright did, however, fill in some of the gaps. Part of the problem has always been that both Wernher and Beit, like nearly all the other goldbugs and for that matter diamond-bugs , confused their tracks by destroying many of their personal papers. Julius, in spite of his great wealth and prestige, was a retiring man. He was a friend of leading politicians but hated becoming involved in politics, and avoided publicity. He also had few interests outside his business and collecting. His acquisition of Luton Hoo and of Bath House on Piccadilly was probably done to please as Beatrice Webb unkindly put it his society-loving wife. Indeed, as I was to discover, with certain important exceptions, especially during a time of prolonged private agony near the end of his life, the few revelations about this determinedly secretive man were embedded in correspondence with his business partners in South Africa.

I confess that I began to worry about tackling Julius when I read a diary entry by Bertrand Russell about meeting him in 1904, and even more so when confronted by Hilaire Bellocs scathing poem, Verses to a Lord. These, coupled with Thomas Pakenham s history of the Boer War, seemed to present Julius as a kind of demon, with blood on his hands, in cahoots with Joseph Chamberlain and Lord Milner. But I had already decided that it was not within my scope to delve into the rights and wrongs of the Boer War, in spite of my instinctive antipathy towards Cecil Rhodes. I did of course want to establish Juliuss view on the War, and to find out if there was any evidence of his colluding in the Jameson Raid. There was also the question of Chinese slavery in Johannesburg, for which he was undoubtedly one of those responsible and which brought down the Conservative Unionist government in Britain. In fact it became clear to me that the real reason for his success,