Contents

For Lucille

Chapter 1

The Beretta in the Nightstand

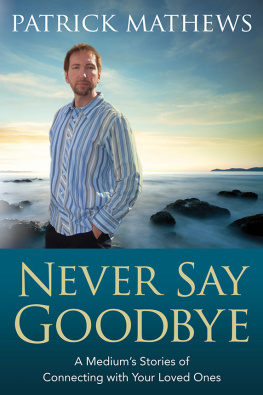

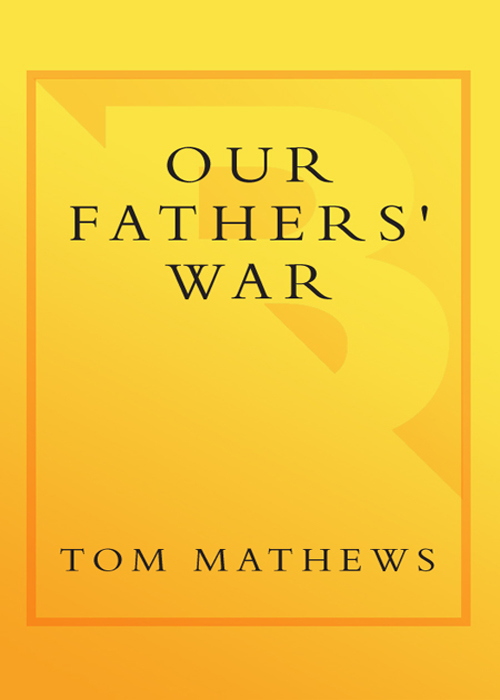

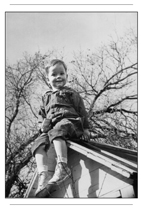

Lt. Thomas Richard Mathews, Camp Hale, Colorado, 1944

M y father hated war stories. He was a soldier with a code, a brave man who wouldnt talk about World War II. For a long time after the war, he could bring himself to tell only one story, and that one happened to him on the day he got home. He was crossing the Rockies in a troop train, safely out of the Apennines, glad to be alive. When his train reached Helper, Utah, it stopped to pick up a booster locomotive for the steep haul over the mountains to Salt Lake City. The sun was just coming up, and hundreds of soldiers were still dozing in their seats. Suddenly, just beyond the windows, the dawn erupted in rifle shots, shotgun blasts, and pistol fire. The Japanese had surrendered, and every man in Helper was shooting up the sky.

No one had bothered to tell the soldiers. Aboard the train, every man in uniform hit the floor. If you were a civilian, you might actually believe that World War II was over; if you had seen combat, it would never be over: You would carry it for the rest of your life, wired into your soul and central nervous system. Within Lt. Thomas Richard Mathews, every synapse was still sparking that day as a Union Pacific Challenger coupled itself to the troop train and started to roll, shoving its load of stouthearted men up the last grade and over Soldier Summit, delivering them home to be fathers.

Now, on this hot August day in 1945, its a few hours later.

On the far side of the mountains, Thomas Richard Mathews Jr. is getting ready for inspection. Its the afternoon before my second birthday. Dressed for a double celebration in clean white shirt, short pants, and scuffed Buster Brown shoes, I am perched on the roof of a garage behind a small brick house on Mill Creek, the safe holding lie where my mother and I have spent the final months of the war. The idea is to get a good look at my father without getting too close too soon. My observation post isnt really a garage, but I dont know that yet. Topping out at about three feet tall, Im still short on inches and nouns: To me, if a building has a front door and it isnt a house, it must be a garage. Im also a little vague about the nature of this inspection, not quite sure which of us is on display. All I know is that the war, whatever that is, has ended; a uniform, whatever one looks like, will be on my father; and my father, whatever a father might be, is just about to appear.

Todays the day, Tommy Two! Todays the day!

Just a few minutes earlier, my mother had sung her small fanfare as she picked me up and waltzed me across the kitchen of our dark basement apartment. Her joy made me frown. My father and I both have the same name; we are both first sons, alphas to the max; and although Im still working on my milk teeth, sharing my mother with anyone bigger than me isnt part of my master plan. None of this I can put into words, of course, but what I am feeling obviously shows on my face.

Tommy Two, the view from the garage, Salt Lake City, 1945

Dont you worry, Tee-Two, my mother says gaily, kissing my forehead. You are my golden-haired boy.

I dont know what shes talking aboutmy hair is not blond; its dark brownand now, more than a little suspicious, Im on top of the garage waiting to get a good look at her soldier. I dont remember anything about the young rock climber and skier who shipped out with the 10th Mountain Division to fight the Germans in northern Italy. He left a few months after my first birthday. I never think about him. To tell the truth, the only thing that piques my curiosity now is his uniform.

From the roof, I have a commanding view of our weedy backyard. Suddenly the door to our subterranean apartment flies open and my father steps out, blinking in the bright August sun. My first impression is this: He is huge. My second impression is that he is a man without a stomach, quite different from my grandfather, whose web suspenders strain against his friendly girth when he hauls himself into his Chrysler. My father is flat and hard where my grandfather is round and soft, and he is moving toward me at a very fast clip. Pulling up in front of the garage, he opens his arms.

Jump.

I hesitate, study the distance between us. It is transcontinental. The drop to the ground appears to be fifteen hundred feet. Bottom of the Grand Canyon. Certain death.

Jump.

Not possible. No, no, no, no, no.

I said jump. The voice is harder now. But then, for just an instant, he appears to soften.

Its okay, Tommy, he says. Im your father.

Am I supposed to fly? Does he think Im a bird? Recoiling, I freeze to the roof.

The tanned face flushes. Then the soldier wheels abruptly and storms across the yard, plunging into the basement. For the rest of my life I will hear the screen doors sharp bang and the last thing he said before he turned his back and walked away.

No son of mine is a coward.

In memory, this first scene always plays out in the present tense, arriving through an odd quantum leap that makes the collision from the past and its impact today coincide in time. I wanted my fathers love, he longed for mine; but from the day he came home, the kinetic energy of World War II struck at our center of gravity. To what might otherwise have been the normal, primordial course of battle between fathers and sons, the war added its own peculiar convolutions. In our case, from that first day, my father thoughtnot without reasonthat he was looking at a soft little pain in the neck, and I thought, on balance, that my life would be off to a better start if only the Germans had killed him.

The issue between us wasnt a simple one of who was boss. It was more a question of who was who. I could never quite figure out where he left off and I began. World War II may have been the last war where young men actually sang as they were bound for combat: in their barracks, on the troopship, in the trucks moving them up to the front line. The 10th Mountain Division had a ballad called Ninety Pounds of Rucksack about a barmaid who jumped into a skiers bed to keep him warm and wound up with a bastard in the mountain infantry. The chorus was Ninety pounds of rucksack, a pound of grub or two. Hell schuss the mountains like his daddy used to do. The big bastard was my father, and the little bastard was me. When I was a small boy, we both thought it was my destiny and duty to follow his smooth, shining track on the hill.

The problem was that the tracks were clear only in light powder snow. The war and what came after made him a hard man to understand. He had grown up during the Great Depression feeling like a boy with empty pockets standing outside a candy store window. After the war, you could never be sure how he felt. My sister once sent me his photograph from Officer Candidate School. In this formal portrait, shot in a studio somewhere near Fort Sill, Oklahoma, he is twenty-one years old. Sewn to his shoulder is a 10th Mountain Division patch: two red bayonets crossed on a field of blue. The stitches on the patch are large, as if he has done the sewing himself. Mercifully, someone with an airbrush has erased the acne that scarred his adolescence. For the first time, he is actually good-looking: hair dark and brushed up in an unmilitary wave, a faint smile, lady-killer eyes.

Next page