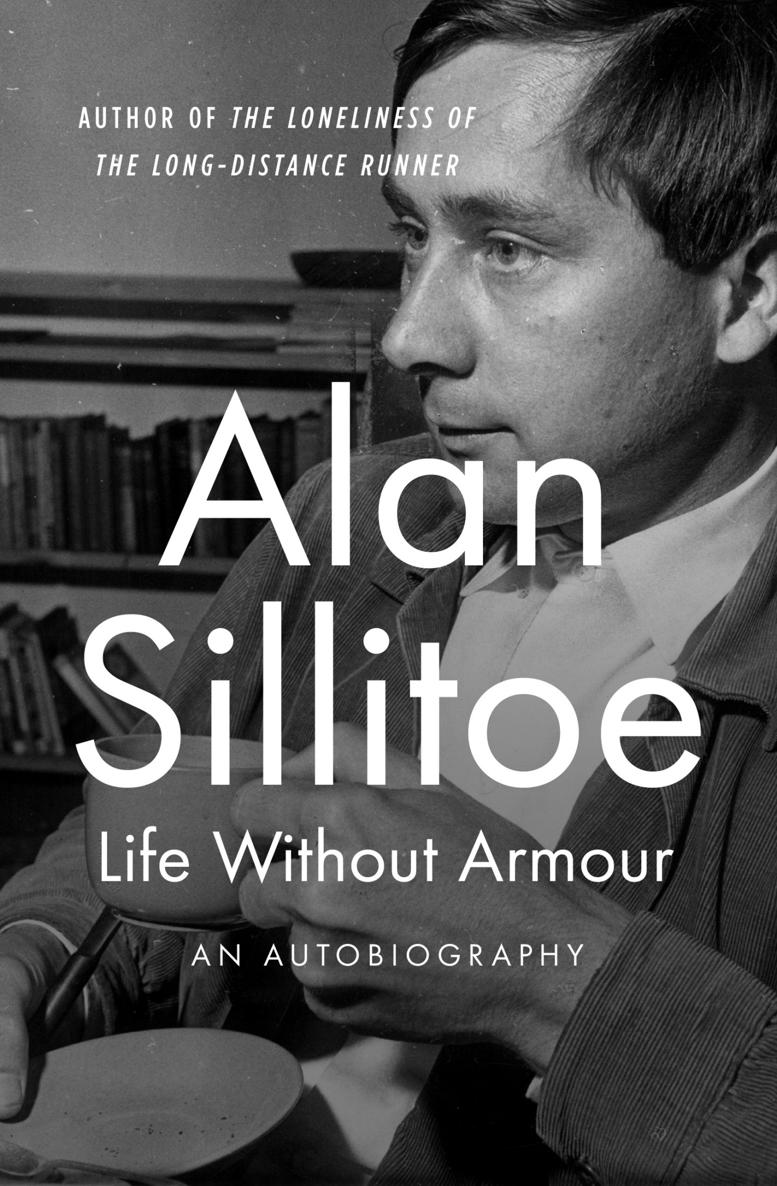

Chapter One

An autobiography is bound to give details of more people than its author, even if only to mention the two who were responsible for him being born. With regard to my father, I have never been able to decide on the mental age at which he was stalled during much of his life. I am now well past the age of his death, over thirty years ago, yet recall that he sometimes seemed to have the mind of a ten-year-old in the body of a brute. He was short-legged and mega-cephalic, and what is certain is that given millions of years and a typewriter he would never have produced a Shakespearean sonnet. On the other hand, neither would I.

Much of the time he had the ability to conceal his backwardness, of which in some obscure dell of the mind he was indeed aware. His experience of the world helped, for he also had that self-centred kindness which brutes are said to possess, realizing that if he wanted affection from those around him he must show something similar to draw it out.

He often hit my mother, and an early memory is of her bending over the bucket so that blood from her cut head would not run on to the carpet. His way of atonement was to be helpful in a sentimental sort of way, but he became dangerously baffled when such gestures evoked revulsion. My mother decided early on that since it was his only form of truce she had better accept them, because not to do so could bring another squall of violence. She also knew that taking advantage of his sudden mellowing eased the pain of his existence and so, under the circumstances, she honoured the maxim that since you had made your bed you must lie in it.

The slow unrolling of age should have taught my father to know himself, and thus control his worst instincts. Unable to do so, he remained a menace to those nearby. I soon learned to think before I spoke, especially to people I feared, which included nearly everyone, a not unusual state for an infant. My father wielded the ultimate authority of the fist and the boot, tempered if that is the word by a fussiness which was only another form of self-indulgence, thus giving me an enduring disrespect for authority.

In those early days such black moods took up more of my fathers time than his genuine need to make amends, so my sister and I lived in continual apprehension of someone who, we sometimes felt, should have been kept on a chain. We responded to his moments of kindness with relief rather than affection, but there was no haven of trust in either of our parents. My mother wanted to ameliorate my fathers unpredictable rages, and suffered doubly because she could not, being unable even to protect herself. I recall her cry of protest, however, when my father was battering me an infrequent event, for I soon learned to keep out of his way: No, no, not on his head! I also experienced twinges of despair at my mother having met him and given me birth, though my spirit adapted speedily to something like that of a courtier in the cage of an orang-utan.

From the beginning my emotions were divided between hatred of my father and pity for my mother, but I occasionally realized that my father might be the way he was because he could not read and write. He was deeply ashamed when we children heard our mother shout in her anguish that he was a numskull unable even to decipher a street name or bus sign. The world thus seemed like a mystifying jungle, and I write about him because he was the first threatening force encountered on my coming out of the womb, though his presence was probably felt while I was still in it.

Apart from disturbances inherited, he was probably paying back what had been done to him since birth, indicating that he did not have the mental flexibility to control himself like a civilized person. The fact that I did not pass on such disadvantages to those who later surrounded me was because I identified, as who would not, with my mothers sufferings, and not with an anger which could always be turned on to me.

My mother, Sabina Burton, was one of eight children (for all that such data are worth), daughter of Ernest, himself the youngest of ten children, and a blacksmith from generations of the trade. He had married Mary Ann Tokins, a barmaid of Irish descent from County Mayo, her grandparents having left with their six sons during the Great Hunger of the 1840s.

Christopher Archibald, my father, was the last and eighth child of Ada Alice, and of Frederick Sillitoe who had an upholstery business. Frederick was the son of Sarah Tomlinson and John Sillitoe, who was a tinplate worker in Wolverhampton. Ada Alice was the daughter of Mary Jane Hillery, and of Henry Blackwell who worked as a hosiery warehouseman in Nottingham.

My father might claim, in an amiable attempt to explain his outlandish surname, that there was an Italian far back in the wayward stepping stones of the familys progress. Some thought he might be right, because of his black hair, before he went bald, brown eyes and sallow complexion, though I was to believe less and less in such stereotypes the further I got from him.

Sillitoe is an old English name, which gave much trouble to those Victorian specialists in family nomenclature, one writer suggesting that it may have originated in Iceland, and another stating that it came from North Yorkshire. Whatever the truth, it might be fair to say that my father had some of the oldest English traits. On my birth certificate he is described as engineers labourer. Since that was also my first job, I may have taken something from him after all, though exactly what it was I have never been able to decide.

When old man Sillitoe, the upholsterer, died in 1925 he left the proceeds of several slum houses in Wolverhampton to be divided between his eight children, none of whom had known he owned property. The eldest son, Frederick Wallace, a lace designer by trade, had a few years earlier hired a pantechnicon and loaded into it all the unpaid-for high quality furniture of his house, and gone to live in London, where he stayed twenty years. He changed his name and did not let the family know his address, which meant he could not be traced by his creditors nor found for the paying out of the inheritance. His share went to the others, thus tempering my fathers story of the exploit with the truth that what you gained on the swings you inevitably lost on the roundabouts.

![Johnson - This boy: [a memoir of a childhood]](/uploads/posts/book/185323/thumbs/johnson-this-boy-a-memoir-of-a-childhood.jpg)