A.J.P. Taylor - Bismarck: The Man and Statesman

Here you can read online A.J.P. Taylor - Bismarck: The Man and Statesman full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1967, publisher: Vintage, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Bismarck: The Man and Statesman

- Author:

- Publisher:Vintage

- Genre:

- Year:1967

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Bismarck: The Man and Statesman: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Bismarck: The Man and Statesman" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Bismarck: The Man and Statesman — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Bismarck: The Man and Statesman" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

eISBN: 978-0-307-78742-2

VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION , September, 1967

Copyright, 1955, by A. J. P. Taylor

All rights reserved under International

and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published

in New York by Random House, Inc.

Reprinted by arrangement with Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

VINTAGE BOOKS are published by

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. and Random House, Inc.

v3.1

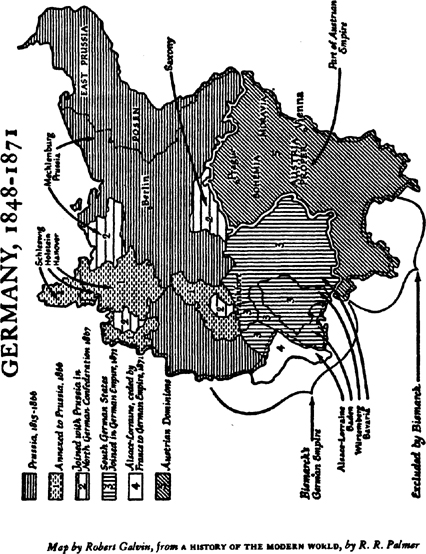

Map by Robert Galvin, from A HISTORY OF THE MODERN WORLD , by R. R. Palmer

THE BOY AND THE MAN

O TTO VON B ISMARCK was born at Schnhausen in the Old Mark of Brandenburg on 1 April 1815. Both place and date hinted at the pattern of his life. Schnhausen lay just east of the Elbe, in appearance a typical Junker estatesome sheep and cattle, wheat and beetroot fields, with woods in the background. Life seemed to follow a traditional rhythm, far removed from the modern world. Yet if Bismarck had been born two years earlier, the kingdom of Westphalia, ruled by Jerome Bonaparte, would have been just across the river. French troops had occupied Schnhausen during the wars; French revolutionary ideas lapped to the edge of its fields. The true Junkers lived far away to the east, in Pomerania and Silesia. These Junkers were a Prussian specialitygentry proud of their birth, but working their estates themselves and often needing public employment to supplement their incomes. They looked with jealousy at the high aristocracy with its cosmopolitan culture and its monopoly of the greatest offices in the state. We may find a parallel in the English country-gentry with their Tory prejudices and their endless feud against the Whig magnates; but the Junkers were nearer to the soil, often milking their own cows and selling their wool themselves at the nearest market, sometimes distinguished from the more prosperous peasant-farmers only by their historic names.

Schnhausen was an estate of this kind, but the winds of the modern world blew round it. Though Bismarck was born a couple of miles on the Junker side of the Elbe, he was always the Junker who looked across itsometimes with apprehension, sometimes with sympathy. The date of his birth was also significant. A fortnight earlier Napoleon had arrived in Paris for his last adventure of the Hundred Days. The old order had a narrow escape. Bismarck, despite his appearance of titanic calm, was always aware of the revolutionary tide that had threatened to engulf the antiquated life of Schnhausen. The kingdom of Prussia, of which he was a subject, had risen again into the ranks of the Great Powers, but it had been almost snuffed out by Napoleon. Her statesmen feared that the same fate might come again. It became their dogma: Unless we grow greater we shall become less. This was no basis for a confident conservatism.

The very geography of Schnhausen also shaped Bismarcks character and political outlook. It was unmistakably in north Germany, in a district entirely inhabited by Protestants. Bismarck never came to regard the south Germans as true Germans, particularly if they were Roman Catholics. Yet Schnhausen also lay far from the sea. Its inhabitants looked to Berlin as their metropolis; and the connexion which Bismarck later established with Hamburg was always rather artificial. If Germany was to expand at all, he preferred that it should be overseas rather than down the Danube; yet both were alien to him. The eastern expansion of Prussia, which had shaped her history, was equally remote for him. Unlike the Junkers of Silesia or West Prussia, he never had a Pole among his peasants. The Poles whom he denounced from personal experience were educated revolutionaries, not workers on the land; it was because of them that Bismarck disliked intellectuals in politics.

There was a similar contradiction in his family heritage. His father Ferdinand was a typical Junker, sprung from a family as old as the Hohenzollernsa Suabian family no better than mine Bismarck once remarked. Schnhausen itself symbolized their humiliation; for they had received it as compensation for their original family estate, which a Hohenzollern elector had coveted and seized. The Bismarcks had done nothing to gain distinction during their long feudal obscurity. Ferdinand did not even exert himself to fight for his king. He left the Prussian army at 23; and missed both the disastrous Jena campaign in 1806 and the war of liberation against Napoleon in 1813. The efficient management of his rambling estates was beyond him, and he drifted helplessly into economic difficulties. It needed a vivid imagination for the son to turn this easy-going, slow-witted man, with his enormous frame, into a hero, representing all that was best in Prussian tradition.

Wilhelmine, the mother, was a different character. Her family, the Menkens, were bureaucrats without a title, not aristocrat landowners. Some of them had been university professors. Her father was a servant of the Prussian state, prized by Frederick the Great and later in virtual control of all home affairs. His reforms and quick critical spirit brought down on him the accusation of Jacobinism. Wilhelmine was a town-child, at home only in the drawing rooms of Berlin. She had a sharp, restless intellect, which roamed without system from Swedenborg to Mesmer. At one moment she would be discussing the latest works of political liberalism; at the next dabbling in spiritualist experiments. Married to Ferdinand von Bismarck at sixteen, she developed interest neither for her heavy husband nor in country life. All her hopes were centred on her children. They were to achieve the intellectual life that had been denied to her. Her only ambition, she said, was to have a grown-up son who would penetrate far further into the world of ideas than I, as a woman, have been able to do.

She gave her children encouragement without love. She drove them on; she never showed them affection. Otto, the younger son, inherited her brains. He was not grateful for the legacy. He wanted love from her, not ideas; and he was resentful that she did not share his admiration for his father. It is a psychological commonplace for a son to feel affection for his mother and to wish his father out of the way. The results are more interesting and more profound when a son, who takes after his mother, dislikes her character and standards of value. He will seek to turn himself into the father with whom he has little in common, and he may well end up neurotic or a genius. Bismarck was both. He was the clever, sophisticated son of a clever, sophisticated mother, masquerading all his life as his heavy, earthy father.

Even his appearance showed it. He was a big man, made bigger by his persistence in eating and drinking too much. He walked stiffly, with the upright carriage of a hereditary officer. Yet he had a small, fine head; the delicate hands of an artist; and when he spoke, his voice, which one would have expected to be deep and powerful, was thin and reedyalmost a falsettothe voice of an academic, not of a man of action. Nor did he always present the same face to the world. He lives in history clean-shaven, except for a heavy moustache. Actually he wore a full beard for long periods of his life; and this at a time when beards were symbols on the continent of Europe of the Romantic movement, if not of radicalism. In the use of a razor, as in other things, Bismarck sometimes followed Metternich, sometimes Marx. Despite his Junker mien, he had the sensitivity of a woman, incredibly quick in responding to the moods of another, or even in anticipating them. His conversational charm could bewitch tsars, queens and revolutionary leaders. Yet his great strokes of policy came after long solitary brooding, not after discussion with others. Indeed he never exchanged ideas in the usual sense of the term. He gave orders or, more rarely, carried them out; he did not co-operate. In a life of conflict, he fought himself most of all. He said once: Faust complains of having two souls in his breast. I have a whole squabbling crowd. It goes on as in a republic. When someone asked him if he were really the Iron Chancellor, he replied: Far from it. I am all nerves, so much so that self-control has always been the greatest task of my life and still is. He willed himself into a line of policy or action. His friend Keyserling noted of his conversion to religion: Doubt was not fought and conquered; it was silenced by heroic will.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Bismarck: The Man and Statesman»

Look at similar books to Bismarck: The Man and Statesman. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Bismarck: The Man and Statesman and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.