Contents

Guide

Page List

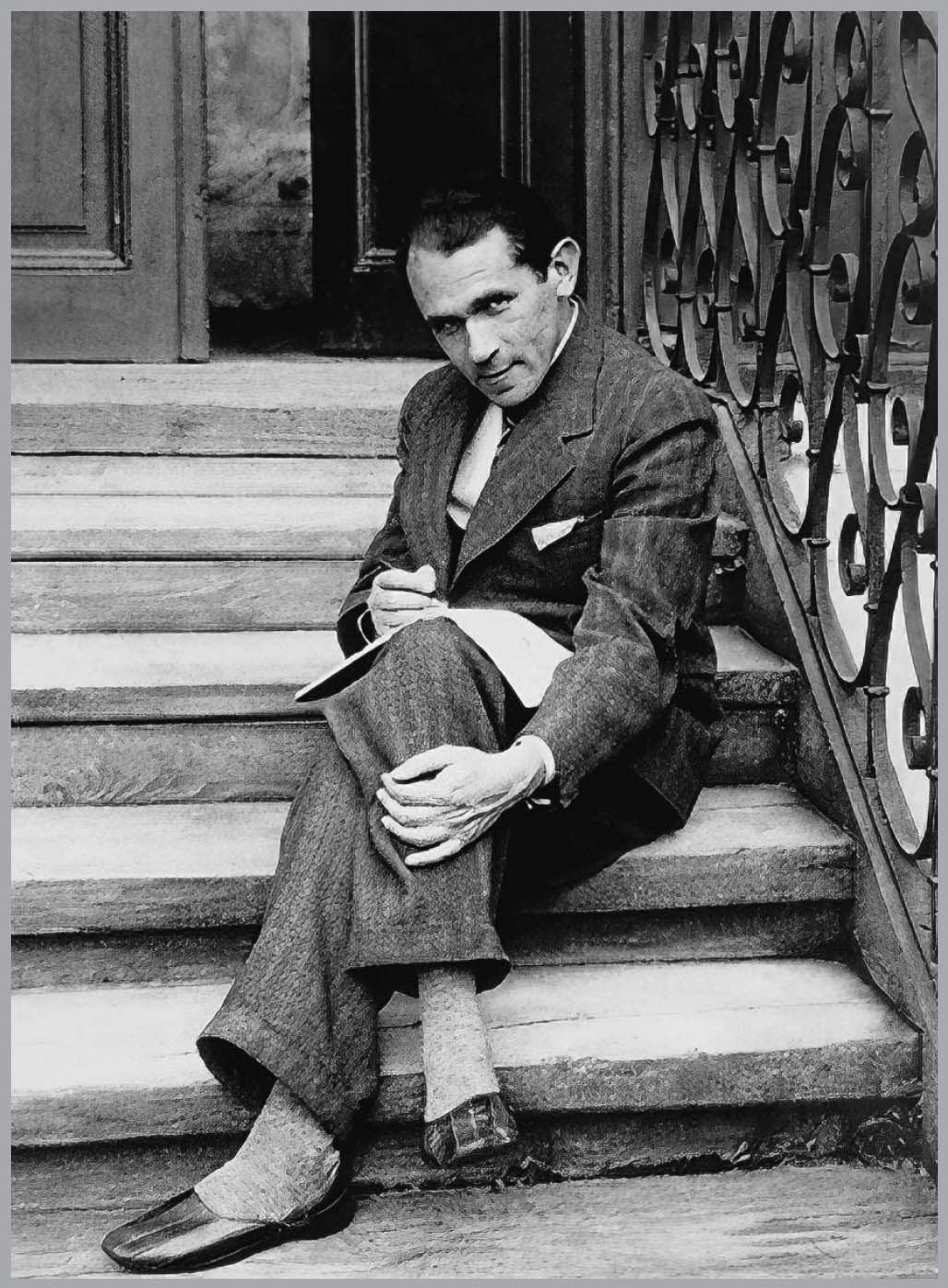

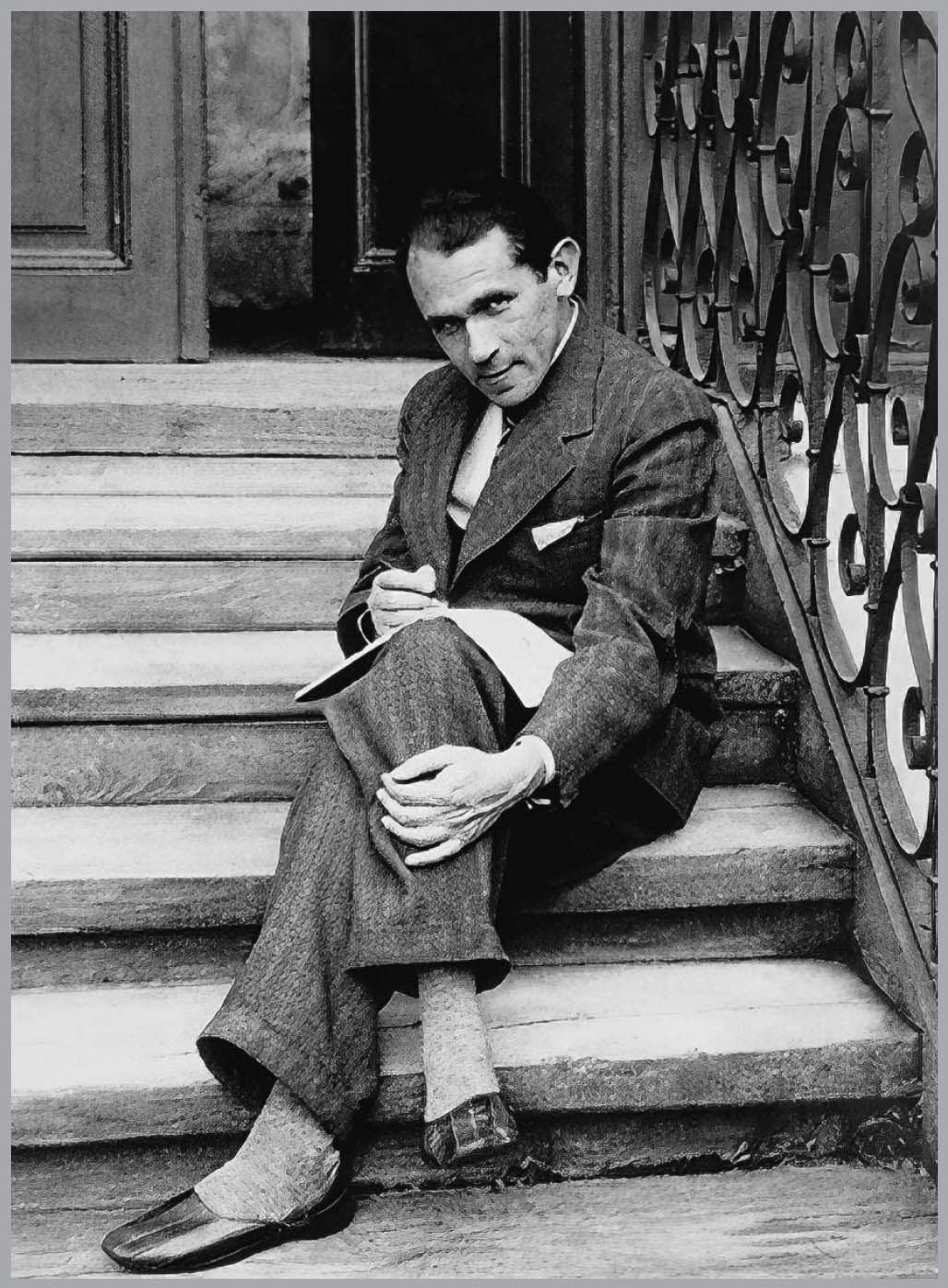

Bruno Schulz on the steps of his home, Drohobycz, Poland, 1933 (Bertold Schenkelbach).

For Ida

CONTENTS

BRUNO SCHULZ

The fragmented murals I saw that morning at Yad Vashem, Israels Holocaust museum in Jerusalem, seemed both perishable and permanent. Formally untutored in painting, the artist had used a fresco secco (dry fresco) technique, applying paint directly to dry plaster to create fanciful figures held in lucid stillness. The technique allows for an immediacy of gesture. Though the gaily colored fairy-tale scenes painted in 1942 had been muted by time, even today, eight decades later, and even to my untrained eye, something alive inhabited the brushstrokes, traces of a past espousal of passion that had not quite disappeared. In their dissolving contours, the murals support contemplation and require our complicity; they invite us to speculate, to fill in whats missing. They merge in the mind more than in the eye.

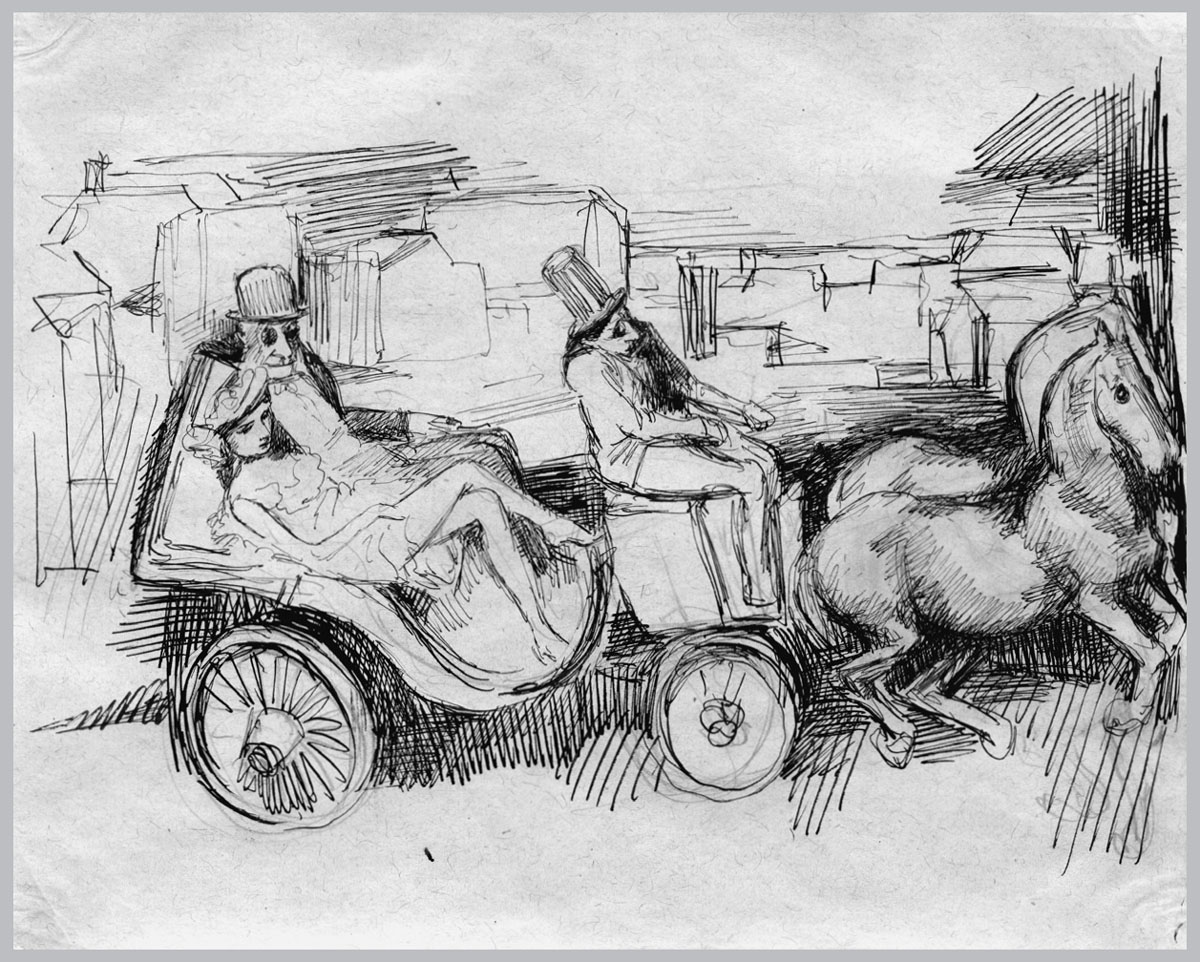

One rough-hewn fragment depicts a seductively dressed, resplendent Snow White surrounded by red-hatted gnomes. One gnome seems to bear the time-ridden face of the painters father, Jakub. Another tableau features a colorful carriage drawn forward on clattering wheels into an uncertain distance by two splendid horses ready to canter away, their progress brought to a halt, their forelegs suspended in midair. The vigilant, proud, blue-helmeted driver holding the reins like a charioteer is the painter himself. It is the doomed artists last self-portrait, and maybe, too, a last act of resistance against the effacement of his individuality.

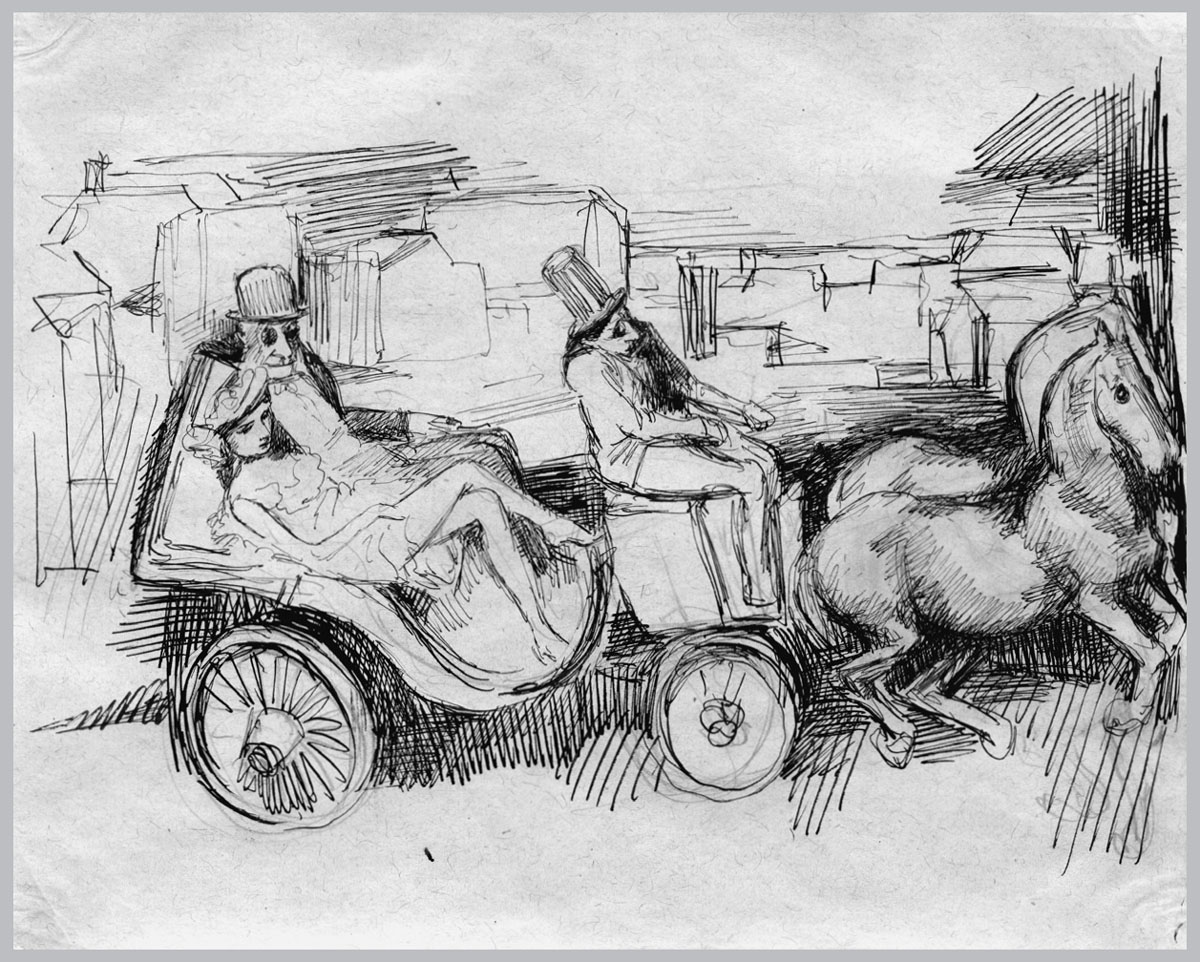

Throughout his life, this artist had drawn horse-drawn carriages sweeping through the dark. He once wrote to a friend of his earliest scribbles:

Before I could even talk, I was already covering every scrap of paper and the margins of newspapers with scribbles that attracted those around me. At first, they were all horses and wagons. The action of riding in a carriage seemed to me full of weight and arcane symbolism. From age six or seven there appeared and reappeared in my drawings the image of a cab, with a hood on top and lanterns blazing, emerging from a nocturnal forest. That image belongs to the basic material of my imagination and to this day I havent exhausted its metaphysical content.

Bruno Schulz, Bianca and Her Father in a Coach (c. 1936), an illustration for his book Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass ( CREDIT: Yad Vashem)

During the Holocaust, the Polish Jewish artist and writer Bruno Schulz was coerced by a Nazi to paint these murals on the walls of a childrens room in an SS villa in the then-Polish, now-Ukrainian city of Drohobych. (References in this book to the city at a time when it belonged to Poland will use the Polish spelling, Drohobycz.) Long before the war, Schulz had created unnerving masochistic scenes, depictions of men groveling at womens feet. These caught the eye of the sadistic SS officer with a Jewish stepfather who would serve as Schulzs guardian devil and would determine Schulzs fate. In this uneasy alliance, Schulzs art became the currency with which he bought life.

When I stood before those murals at Yad Vashem, I couldnt help but imagine the artist sapped of his vitality, compelled to flatter the fancies of his master, forced to flounder somewhere between Lebensraum and Todesraum (living space and death space), hourly reminded of his status as a disconsolate prisoner of an enemy who wished to dehumanize him. I wondered whether he painted his desire to seize the reins of his own narrative, to reclaim dignity. (One of the verbs in the Nazi vocabulary of Jew hatred, itself an outrage against dignity, was entwrdigen, to deprive of dignity.) By my very nature, Schulz remarked, I am not made to offer resistance, to stand up for myself, to defy the will of another person. I dont possess the necessary strength of conviction, the narrow faith in the rightness of my cause, for that. Yet if the art he had earlier created with the free play of his imagination is servility made visible, the art he created under the most coercive conditions depicts unflinching freedom. Did he manage to control his brushstrokes without letting the fear slip out through his fingers? Could he summon dignity, even defiance?

Schulzs story did not end with the bullet that took his life in November 1942. Nearly sixty years after Schulz was murdered, his muralswitnesses to human crueltywere miraculously rediscovered. Several months later, three Israeli agentsaided by bribery, spycraft, and diplomatic immunitychiseled them from the villas walls and secretly spirited the fragments to Yad Vashem, perhaps the only museum in the world guided by the injunction to remember as both a national and a religious imperative. The ensuing international furor, and its excursions into competitive martyrology, revived questions about Schulzs life and went to the very heart of Jewish and European memory (or how Holocaust memory becomes an object of realpolitik) and of the political implications of who controls cultural heritage.

Drawing on extensive new reporting, archival research, interviews (in Poland, Ukraine, and Israel), and scattered letters and memoirs, Bruno Schulz chases these inventive muralsthe last traces of his vanished worldinto multiple dimensions of Schulzs life and afterlife.

SCHULZ WAS BORN AN AUSTRIAN, LIVED AS A POLE, AND DIED A JEW . His life began under the banner of the Austro-Hungarian double-headed eagle and ended in the genocidal dehumanizations of Nazi occupation. Born a citizen of the Habsburg monarchy, Schulz wouldwithout movingbecome a subject of the West Ukrainian Peoples Republic (November 1918 to July 1919), the Second Polish Republic (1919 to 1939), the USSR (September 1939 to July 1940), and, finally, the Third Reich. Yet to use his own metaphor, Schulz remained throughout a citizen of the Republic of Dreams.

The cartographer of that republic was both a graphic artist and a master of twentieth-century imaginative fiction, a powerful writer who mapped the anxious perplexities of his time, who used the Polish language as dexterously as if he had made itor even as if the language had been invented for his sake. His polysensual prose, to use his phrase, was touched by the divine finger of poetry. It may very well be the most beautiful ever written in Polish. Modernist classicsJoyces Ulysses, Prousts In Search of Lost Time, Musils The Man Without Qualitiestend to be sprawling. Schulzs literary reputation rests on two slender volumes (some thirty short stories): Cinnamon Shops (1934, published in the United States. as The Street of Crocodiles) and Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass (1937). Yet his elegant verbal art, with its inexhaustible inventiveness, transcends the confines of its chronology. Alternately claustrophobic and boundless, his fables are peopled with an uncanny congress of characters who dream febrile dreams, with streets that turn into labyrinths, with time that circles and eddies. To borrow his own phrase again, Schulzs work represented an enormous, magnificent, colorful blasphemy. That blasphemy made Schulz a venerated and tutelary spirit for a procession of better-known writersincluding Philip Roth, Cynthia Ozick, Nicole Krauss, Jonathan Safran Foer, David Grossman, and Polish Nobel laureates Czesaw Miosz and Olga Tokarczuk. Each felt profound affinities with his many-sided fiction, and with the motifs that course through it. Along with filmmakers and actors, they wove stories out of Schulzs private mythology. Schulzs fiction has been translated into forty-five languages. Yet Schulz, today lionized, would never know his own international success, his afterlife in the brushes and pens of other artists, or the ways posterity would consecrate him into myth. He was killed before he finished saying what he had to say. If Schulz had been allowed to live out his life, said the Polish-born Yiddish writer Isaac Bashevis Singer, he might have given us untold treasures, but what he did in his short life was enough to make him one of the most remarkable writers who ever lived.