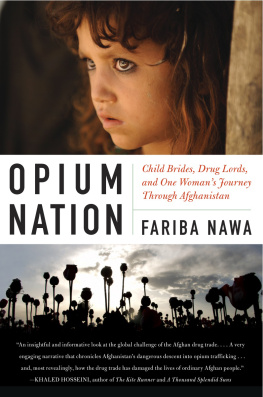

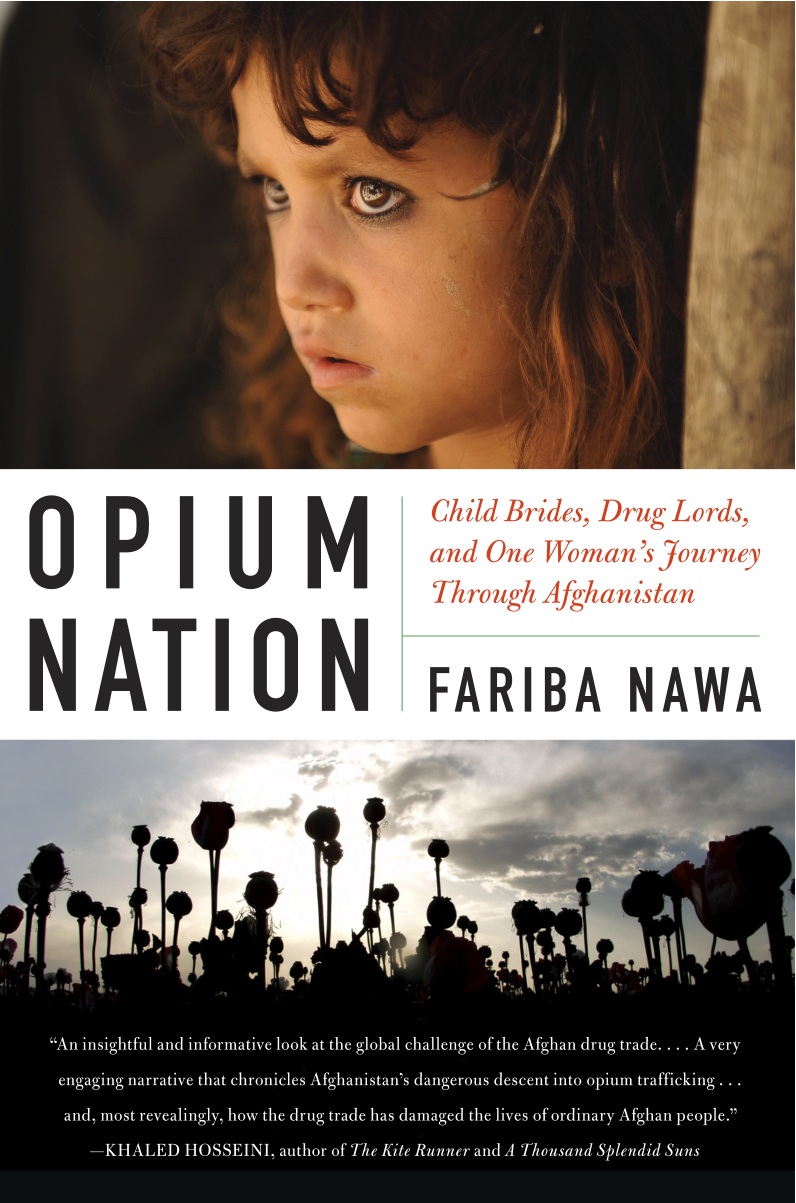

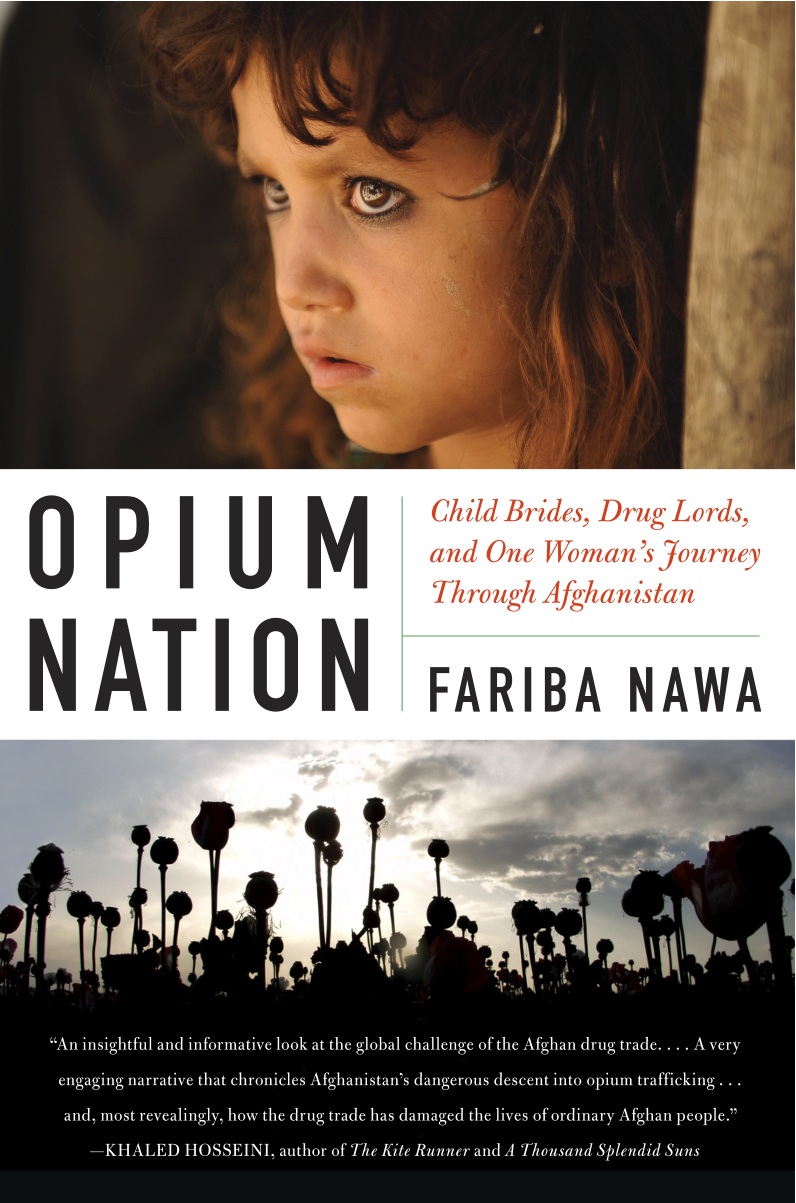

OPIUM

NATION

Child Brides, Drug Lords, and

One Womans Journey Through

Afghanistan

FARIBA NAWA

To my parents, Sayed Begum and Fazul Haq, who introduced me to the Afghanistan of the past, and to my daughter, Bonoo Zahra, who I hope will become a positive force in the countrys future

Contents

In the summer of 2003, I met a girl in an Afghan town straddling the desert who would become an obsession for me. I knew her for only a few weeks, but those few weeks shaped the next four years of my life in Afghanistan. What I remember most about her is her scared look, a gaze that deepened her otherwise blank green eyes. She was the daughter of a narcotics dealer who had sold her into marriage to a drug lord to settle his opium debt. Her husband was thirty-four years her senior, and even her threats to burn herself to death did not change her fate. A year after I met her, she was forced to go to a southern province as the wife of this man, a man who did not speak her language and who had another wife and eight children.

I met Darya on a quest to write a magazine story about the impact of the Afghan drug trade on women. Ghoryan, the Afghan district where she used to live, is two hours from the Iranian border, and the people there make their living on opium transport. In this vast district I met many men and women who were either victims or perpetrators in the worldwide multibillion-dollar drug trade, but none of them stayed in my heart as much as Darya. She had become a child bride and a servant, a casualty of the drug tradean opium bride. Darya is a link in a long chain that begins on Afghanistans farms and ends on the streets of London and Los Angeles. In order to understand what happened to her, I had to understand the drug trade. I chased clues from province to province to find out who was behind the business; who its victims were; how it was impacting Afghans; and what the world, and the Afghan government, were doing to stop it.

In 2000, I made my first trip back to Afghanistan in eighteen years, during Taliban rule, to search for something I had losta sense of coherence, a feeling of rootedness in a place and a people, and a sense of belonging. I had many unsettled emotions toward my homeland, which I had had to flee at the impressionable age of nine. The strongest feelings were aching nostalgia and lingering survivors guilt, which my parents and siblings did not share. I was the youngest, with the fewest memories of the war-torn land, but I longed for it the most. All that my adopted home, the United States, offered me could not make up for the loss I felt in leaving Afghanistan.

In the process of finding ways to deal with my demons, I wanted to tell the world that the Afghan drug trade provided funding for terrorists and for the Taliban, who were killing Americans and strengthening corrupt Afghan government officials whom the United States supported. A former chief of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration called the Afghan opium trade a huge challenge in the world. Americans and the British are directly harmed by it. Afghan heroin is a favorite among addicts because its a potent form of heroin, and increasingly available.

I spent 2000 through 2007 shuttling back and forth between Afghanistan and the United States, with detours to Iran and Pakistan. The majority of my time was spent traveling through Afghanistan. During that time, I witnessed the countrys shift from a religious autocracy to a fragmented democracy and, finally, to a land at full-scale war. The result of that war has been dependence on an illicit narcotics trade, without which the Afghanistan economy would collapse. For the opium trade is the underground Afghan economy, an all-encompassing market that directly affects the daily lives of Afghans in a way that nothing else does.

Ghoryan district, Daryas childhood home, is full of individuals and families with stories few have heard. The Afghan women who live there are not the weak, voiceless victims they are so often made out to be in the Western media. Since they see themselves as part of their family units, Afghan women rarely demand individual rights, as women, something uncommon in the West. During my time in Ghoryan, these women, including Darya, showed me just how powerful they were, and how capable of overcoming their problems.

The effect of the opium trade in Ghoryan is very real. Yet Ghoryan is not the only place where the drug trade resides. In some places, the trade is destroying lives; in others, saving them. During my time in Afghanistan, I was drawn to cities and villages where some chose this illegal business while local warlords force others to dive into it. Opium is everywherein the addict beggars on the streets, in the poppies planted in home gardens, in the opium widows hidden from drug lords in neighbors homes, in the hushed conversations of drug dealers in shops, in the unmarked graves in cemeteries, and in the drug lords garish opium mansions looming above brick shacks and mounds of dust. The dust is a reminder of the destroyed land that opium money seems unable to transform into cement, asphalt, or water.

In this book, Ive changed many of the names to protect the people I write about. In Afghanistan, revealing identities does not just invade privacy but also endangers lives. I also try not to focus on the ethnic rivalries in Afghanistan that have, to my mind, been overemphasized and overanalyzed in the West, though it is impossible to ignore them. After September 11, 2001, many Americans were anxious to know whether I was Pashtun, Tajik, or another minority group. Id stare at them confused and say simply that I was from Herat.

The years I spent working in Afghanistan were the most dangerous and exciting of my life thus far. The action-packed sequence of events I experienced there tested my will to live and set me on a journey to see if the passion I held for my birthplace and its people was rooted in the present or lost in the past.

Chapter One

Home After Eighteen Years

Flies buzz and circle my face. I swat them away as I slowly look up to see a dozen men watching me outside the visa building. Im standing in line at the Iranian border, waiting to cross into my home country, Afghanistan. Men stare at my face and hands. My hair and the rest of my body are covered in a head scarf, slacks, and a long coat, in observance of Irans dress requirements for women.

I keep my eyes to the ground to avoid the ogling. An Iranian border agent calls out my name. My hands tremble as I give him my Afghan passportperhaps the least useful travel document in the world. Ive hidden my American passport in my bra; Iran restricts visas for American citizens, and the Taliban are wary of Afghan women returning from the United States.

Where are you coming from? the agent asks with a serious face.

Pakistan.

What are you doing there?

I work for a charity organization. I actually work for a Pakistani think tank as an English editor, and Im a freelancer writing articles about Afghan refugees in Pakistan for American media outlets. I dont share these details with the Iranian border agent, though; they would only raise more questions and delay my journey.

What were you doing in Iran?

Visiting my relatives.

He eyes me suspiciously and flips through the pages of my passport. Then he stamps the exit visa with Tybad, the Iranian border city, and motions me to leave.

It is late morning and a cool fall breeze hits my face. My hands stop shaking but become clammy, my stomach churns with nausea, my head spins. In just a few hours I will be in Herat, my childhood home, for the first time in eighteen years. The anticipation feels a bit like the moment before I delivered my daughter: painful, frightening, yet exhilarating.