In the Hot Zone

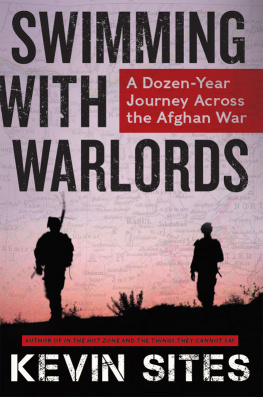

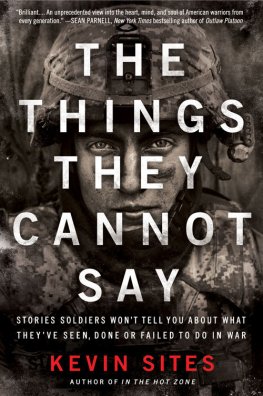

The Things They Cannot Say

All photos copyright Kevin Sites unless otherwise noted.

Some of the material in this book originally appeared in the October 2013 issue of Vice. Excerpts from the authors personal journals have also appeared in the New Times newspaper (San Luis Obispo, CA) from September to December 2001.

SWIMMING WITH WARLORDS. Copyright 2014 by Kevin Sites. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

FIRST EDITION

ISBN 978-0-06-233941-6

EPub Edition October 2014 ISBN 9780062339423

14 15 16 17 18 RRD/OV 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is dedicated to my father-in-law, Gary Smith, who had both roots and wings and lived with the rare and enviable grace of a man who always put others first.

CONTENTS

CLEANSING CONFLICT

What is a saint? One whose wine has turned to vinegar.

If youre still wine drunkenly

brave, dont step forward. When your sheep becomes a lion,

Then come. It is said

of hypocrites, They have considerable valor among themselves!

But they scatter when

a real enemy appears. Muhammad told his young soldiers, There

is no courage before

an engagement. A drunk foams at the mouth talking about what

he will do when he gets his sword

drawn, but the chance arrives, and he remains sheathed as

an onion. Premeditating,

hes eager for wounds. Then his bag gets touched by a needle,

and he deflates. What sort of

person says that he or she wants to be polished and pure,

then complains about being

handled roughly?

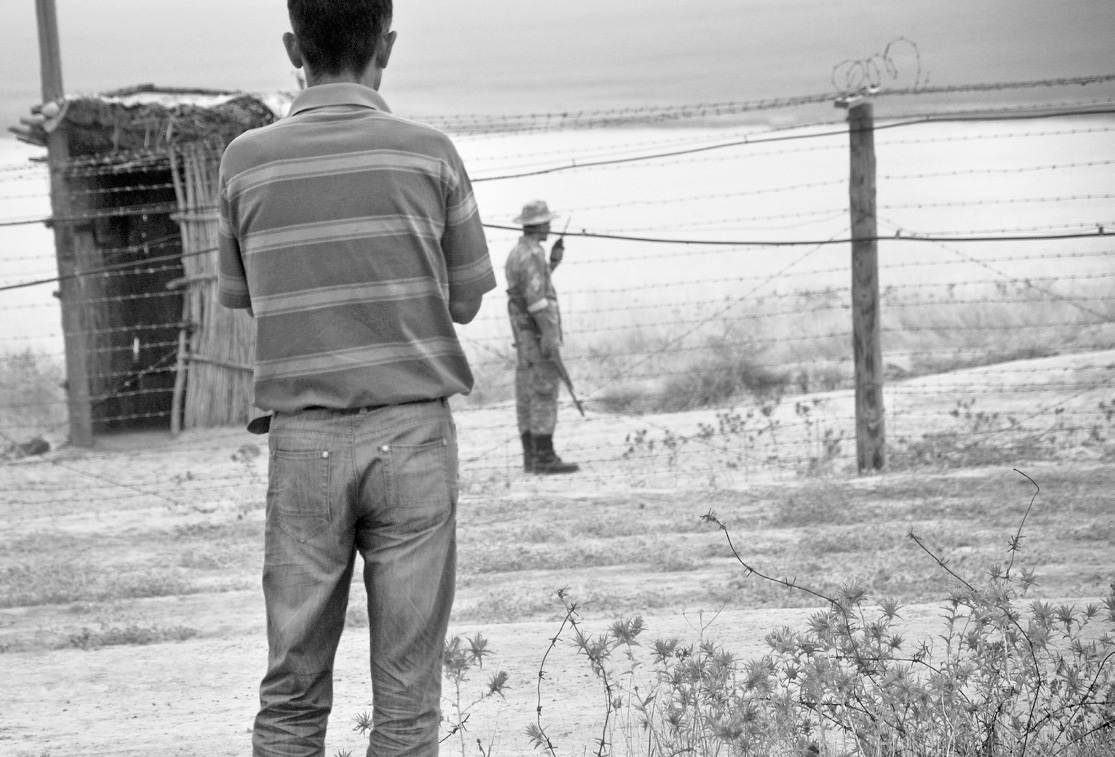

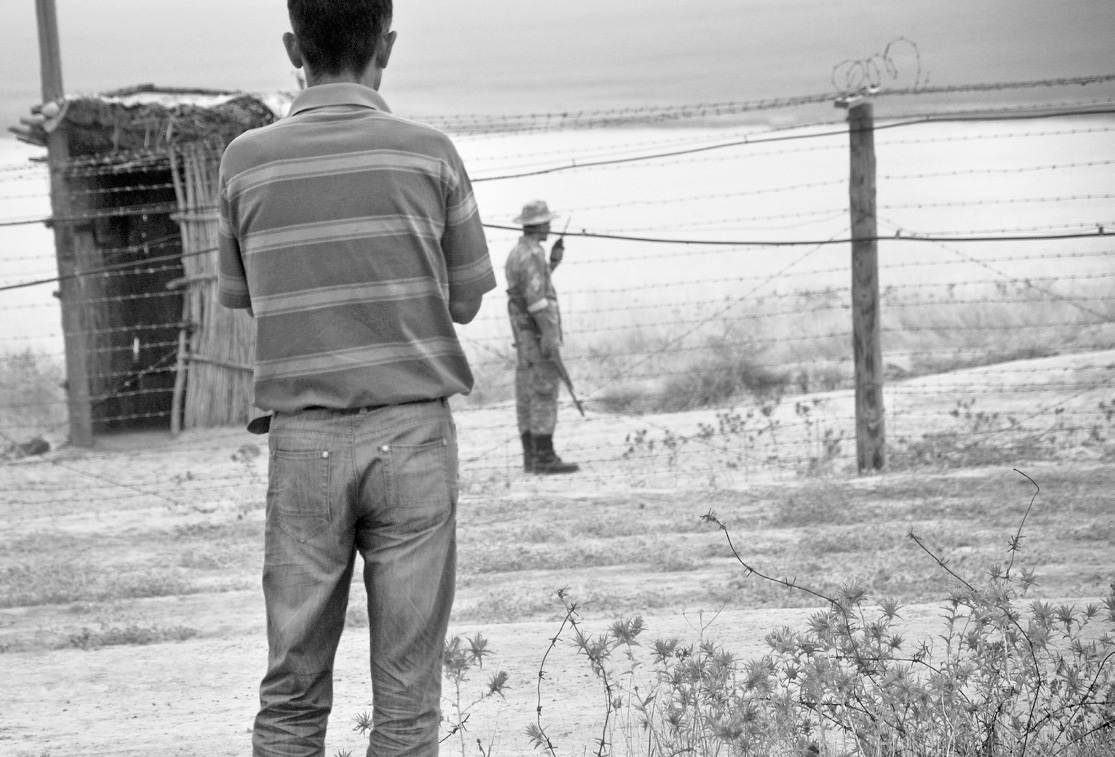

At the Kokol border crossing in Tajikistan, June 2013. My driver has asked the Tajik border guard how long it will take to repair the boat that will ferry me across the Amu Darya River into Afghanistan.

U nder cover of a moonless night in mid-October 2001, I found myself loading thousands of pounds of camera equipment and supplies onto a giant pontoon boat on the northern bank of the Amu Darya River. The pontoons were normally used to carry weapons to the Northern Alliance troops fighting the Taliban on the other side of the water. With all the gear and people, there wasnt any room left on that raft for allegory, but I remember feeling like one of the damned souls in Dantes Divine Comedy about to be ferried across the River Acheron to hell. The American airstrikes had begun, and I was headed into Afghanistan.

It was only one week after Osama bin Ladens Al Qaeda terror network struck the United States, crashing planes into the Pentagon and the World Trade Center. I was dispatched by NBC News to bear witness to Americas righteous anger and retribution. It was swift and unrelenting.

In my first month in Afghanistan, I watched as the U.S. obliterated Al Qaedas bases and, with the help of its Northern Alliance alliesa mix of ethnic Tajik, Uzbek, and Hazara Afghanstoppled the Taliban government that had hosted them. But the war, as we well know, did not end there and has not ended yet.

I went back to Afghanistan in the summer of 2013 for my fifth visit, on the eve of Americas planned withdrawal. My goal was to try to understand what had happened to Afghanistan in the twelve years since I first traveled there, and what might happen this time after I left.

I reentered at exactly same place, crossing the Amu Darya River from southern Tajikistan into northern Afghanistan. The once busy KokolAi Khanoum border crossing, through which weapons, spooks, Special Forces, and journalists like me had once been transported, was now just a dusty shadow of its former self. Today its a remote outpost displaced by real bridges built or refurbished by the Americans and located near larger and busier population centers to help with the flow of commercial goods and war materials moving in and out of Afghanistan.

At the crossing, I found the pontoons moored on the bank, unused because so little cargo was moving back and forth. Instead, I stepped into an ancient, rusted motorboat one weld away from sinking and made the three-minute crossing a second time. As the boat chugged along against the current, I was certain of only one thing: the war I had found on the other side of the river a dozen years ago was there to meet me still.

WATCH A ONE-YEAR-OLD

Anger rises when youre proud

of yourself. Humble that. Use

the contempt of others, and your

own self-regarding, to change, like

the cloud in the folklore that became

three snake shapes. Or if you like

the dog-barking lion wrath, enjoy

the hurt longer. Watch a one-year

old, how it walks, the slow wisdom

there. Sometimes a sweet taste

makes you sour and mean. Listen

to the voice that says, It was for

you I created the universe. Then

kill and be killed in love. Youve

been two dogs dozing long enough!

PART I

THE NORTH

An Afghan National Police officer stands guard, prepared for possible violence between Uzbeks and Tajiks on the streets of Taloqan City.

My second crossing of the Amu Darya River from Tajikistan to Afghanistan. The rusted-out shell of a boat was more seaworthy than it looked. The Amu Daryas strong current forced the captain to throttle hard against it in an upstream arc to ensure we reached our landing spot directly on the other side.

(Photo by Dost Muhammad)

T ajikistan, the poorest of the former Soviet republics, is one of the least visited places on earth, but in June 2013 I was on my way there for a second time. I had traveled there the first time in 2001, with my NBC crew. We had been stymied in our attempts to enter Afghanistan from both Iran and Uzbekistan; Tajikistan would be our final and most reckless attempt. We had traveled thousands of miles by every conceivable means, only to be blocked at each successive border crossing. Desperate to get to Dushanbe, the Tajik capital, we even bribed an entire Tajik flight crew to take a plane overloaded with our gear into the night sky. We thought we would be the only passengers, but after we boarded we were horrified to find that it was filled with other peopleother people whom we might have gotten killed in a plane crash to reach a story that had started with plane crashes on 9/11.

Once in Dushanbe, we drove a few hundred miles south, and in the dark of night crossed the Amu Darya on pontoon boats, aided by Russian soldiers who had covered their faces with kaffiyehs. But the things we did to get there pale in comparison to the adventure that followed. Over the next hundred days, seven of our colleagues would be killed, I would videotape another being blown up by a Taliban mortar, and we would live in the house where legendary mujahedin commander Ahmad Shah Massoud was assassinated. In Kabul, we would unwittingly sleep next to an unexploded 500-pound bomb and discover that our houseboy was being raped by the dirty fuck we had hired for security. I would watch B-52s drop 15,000-pound daisy cutter bombs on the Al Qaeda and Taliban fighters hiding in the mountains of Tora Bora, and in Jalalabad, on my final night of that first Afghan odyssey, I would be visited by what I believed was the spirit of a CNN technician who had died only a day earlier on the very mattress on which I slept.

![Souders - Even faster web sites: [performance best practices for web developers]](/uploads/posts/book/137083/thumbs/souders-even-faster-web-sites-performance-best.jpg)