Kevin Sites

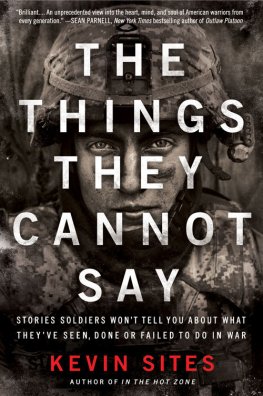

THE THINGS THEY CANNOT SAY

Stories Soldiers Wont Tell You About What Theyve Seen, Done or Failed to Do in War

This book is dedicated to my wife, Anita, and the rest of the party of five, Tina, Cami and Vae, for giving me the gift of being necessary.

A soldier looked at

me with blue hawk-eyes

With kindly glances sorrow had made wise

And talked till all Id ever read in books

Melted to ashes in his burning looks.

Ivor Gurney, British soldier (World War I), poet, composerFrom Ivor Gurney:

Wars Embers(Sidgwick & Jackson Ltd., 1919)

The service ranks, units and campaign deployments listed in the table of contents and the chapter headings reflect the timeline only for the stories depicted in this book. Some of those profiled are still serving in the military and have risen to higher ranks and have fought in additional conflicts. Those promotions and deployments are noted in their postscripts.

Unless otherwise noted, e-mail, social network messages and texts are presented as they were written by their senders.

I welcome your thoughts on the book as well as contributions of new stories from service members around the world that may be collected and published on a companion website. Please send them to me at .

Introduction: The Killer in Me

In combat, inattention to detail can kill people.

Karl Marlantes,

What It Is Like to Go to War

Self-portrait of the author, Lake Erie (2010)

Im a journalist, not a soldier, but Ive killed in combat. This is how I did it: I looked into the eyes of my victim as he begged for his life, lying before me covered in nothing but a ripped shirt, white underwear and his own dried blood, then I shrugged my shoulders, turned and walked away. I killed him with my indifference as much as the twenty-three 5.56 NATO rounds that tracked his spine as he tried to crawl away that few minutes or few hours after I left him in that mosque in south Fallujah. I killed him without wielding a weapon, without being present and without knowing that I had killed him until three years later. It was only in that discovery, reading a heavily redacted Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS) document about the incident, that I learned what I had done. Only in that moment, when the shaky, stacked soapboxes of my belief system came tumbling down, did the other face of war reveal itself to me fully. Until then, I had been happily chasing the dragon, my addiction to war, mostly immune to its consequences. No longer.

Like so many once-young journalists, I was a danger dilettante. In 1986, at the age of twenty-three, I traveled to Nicaragua as a passionate but clueless freelance reporter and photographer for an alternative newspaper to cover the U.S.-backed covert war against the leftist Sandinista government. I had $150 in my pocket, ten rolls of film in a quart-sized Ziploc bag, and a tenuous grasp of even rudimentary Spanish. I was looking for that shortcut to foreign-correspondent street cred, hoping to luck into a firefight, maybe get a bullet graze, but obviously understanding nothing. My research about conducting myself properly in a war zone consisted of watching Oliver Stones Salvador three times. Once in country I headed to the infamous La Cita bar at Managuas Hotel Intercontinental and used my meager cash to buy bottles of the local cerveza, Victoria, for new friends staying at the hotel. After enough rounds, I convinced them to allow me to crash on the floor of their room. Once oriented in the capital, I used a credit card to rent a battered, old Toyota Sentra and drove north from Managua to the front lines with a Canadian military academy professor named Hal, who was kind enough to act as my interpreter and wise enough to realize that I was likely to get myself killed without his help.

I remember weaving through rutted mountain roads on Christmas Eve when two Sandinista soldiers walking along the road stopped us to ask for a ride. Their green jungle boonie caps dripped water from the cowboy-style brims as they loaded into the cramped backseat. I eyeballed the iconic curve of the banana mags jutting from their AK-47s and smelled the smoke of the campfire that they had earlier tried to warm themselves with on that cold, rainy evening. Feliz Navidad, we said to each other as I shifted into first, puttering into the cloud-shrouded darkness. In that moment, I felt I had transcended my small-town Ohio upbringing and had become part of the larger world, one that was comprised of excitement, danger and men with guns. While I never saw combat there, only its aftermath, villagers burying their dead following an attack, it was that first taste that would eventually help make war my heroin. I wanted to feel forever unburdened by the mundane realities of normal life, the way it was so perfectly illustrated by Kathryn Bigelow in her film The Hurt Locker when bomb tech First Sergeant William James is more disturbed by the sight of a well-stocked grocery store cereal aisle at home than of a massive roadside bomb engineered from daisy-chained 155 mm artillery shells in Iraq.

While it would be a decade before I got another real war fix, this time as a producer for NBC News, my high returned easily and quite literally as my feet dangled outside the open door of a Navy Seahawk helicopter hovering over a U.S. destroyer in the waters of the Arabian Gulf, part of the U.S.-led postGulf War no-fly zone enforcement in Iraq. What kind of lucky bastard, I wondered, gets paid to be shuttled back and forth between battleships and aircraft carriers?

A few years after that I watched the start of the war in Kosovo, videotaping million-dollar Tomahawks launched at the Serbian capital of Belgrade from the deck of the guided-missile cruiser the USS Philippine Sea. The killing I witnessed up to and through Kosovo had always been at a distance. I saw weapons release but never their immediate impact. That changed for me during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Killing turns everything on its head. Watching people being killed, especially those you know, is a memory that cant be erased. But actually doing the killing or being fully complicit in it is a lifelong sentence to contemplate the nature of ones own character, endlessly asking, Am I good, or am I evil? and slowly growing mad at the equivocation of this trick question whose answer is definitively yes.

When someone kills in war theres a psychological triage that occurs. The individual must find meaning in the act. Because killing is the ultimate refutation of our own humanity, there must be a justification, to prevent the mind from defaulting to the judgment of murderer.

Its Private Joker trying to explain to the angry colonel in Stanley Kubricks Full Metal Jacket, a 1987 film about the war in Vietnam, as to why hes wearing a peace symbol on his body armor while hes written Born to Kill on his helmet:

Private Joker: I think I was trying to suggest something about the duality of man, sir.

Colonel: The what?

Private Joker: The duality of man. The Jungian thing, sir.

In his book What It Is Like to Go to War former Vietnam War infantry officer and Rhodes scholar Karl Marlantes ruminates on the killing he did and the dying he watched on his deployment to that nation during Americas ten-year conflict there. He learned, in the years after his service, that coming to terms with death is essential, but it has also become increasingly difficult in our age of modern warfare, where death, for many of those meting it out in Iraq and Afghanistan, has become an abstraction.

Self-portrait of the author, Lake Erie (2010)

Self-portrait of the author, Lake Erie (2010)