FATHER OF MONEY

RELATED TITLES FROM POTOMAC BOOKS

Iraq in Transition:

The Legacy of Dictatorship and the Prospects for Democracy

Peter J. Munson

Losing the Golden Hour:

An Insiders View of Iraqs Reconstruction

James Stephenson

FATHER OF MONEY

Buying Peace in Baghdad

JASON WHITELEY

FORMER CAPTAIN, U.S. ARMY

Copyright 2011 by Jason Whiteley

Published in the United States by Potomac Books, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Whiteley, Jason, 1977

Father of money : buying peace in Baghdad / Jason Whiteley. 1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-59797-544-5 (hardcover: alk. paper)

1. Whiteley, Jason, 1977- 2. Civil-military relationsIraqBaghdad. 3. Postwar reconstructionMoral and ethical aspectsIraqBaghdad. 4. Iraq War, 2003-Personal narratives, American. I. Title.

DS79.767.C58W44 2011

956.704431dc22

2011009433

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper that meets the American National Standards Institute Z39-48 Standard.

Potomac Books, Inc.

22841 Quicksilver Drive

Dulles, Virginia 20166

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

for My Brothers

Contents

Acknowledgments

A WARM THANK-YOU to my family, my friends, and my classmates at the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service, who have all heard these stories more times than is humane. Thanks also to Don McKeon for his brutal honesty and relentless editing. Finally, my deepest appreciation and undying admiration for all of the Misfits, without whose support this story would never be told.

Introduction

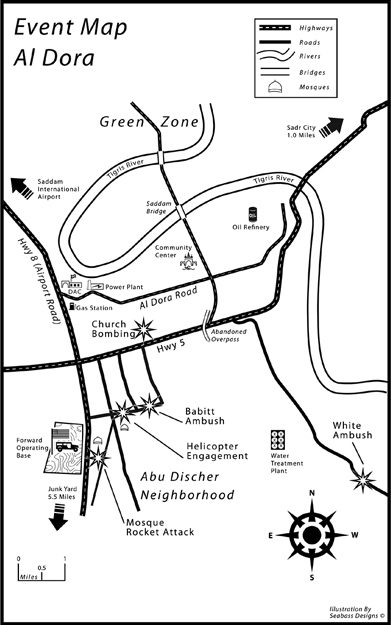

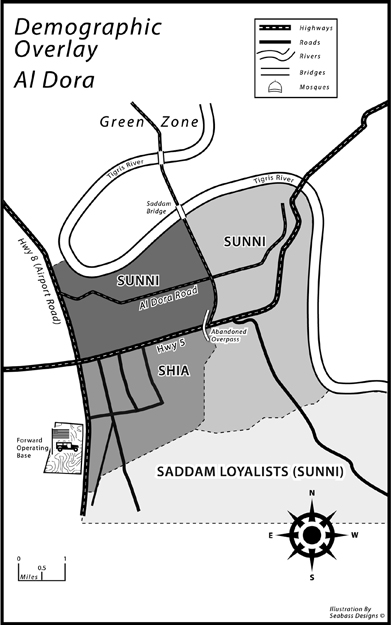

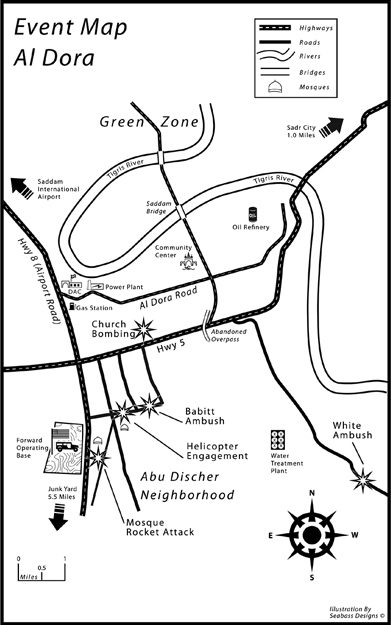

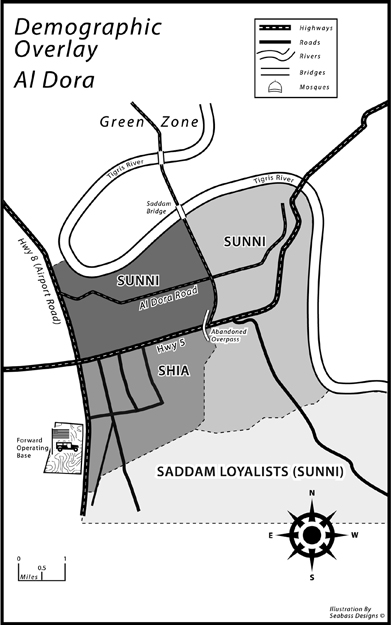

THIS BOOK IS THE STORY of an army officers winding road down into a moral morass, where bribes and blood money, not principle, governed the dissemination of power and the possibility of survival. In March 2004, as a captain in the U.S. Army, I was appointed the governance officer for Al Dora, one of Baghdads most violent districts. My job was to establish and oversee a council structure that would allow Iraqis to begin governing themselves and reconstruct their homeland. I had received no training whatsoever for the postin fact, the role of a governance officer wasnt even part of an armor battalions organizationbut I believed in myself and in what we were trying to achieve in Iraq. I wanted to do something good, something significant. I wanted to help. Yet in a place of extreme violence and devoid of order, the practical subsumes the principle, and I drifted down the path of bribery and corruption that seemed endemic on the streets of Baghdad. Instead of a principled council structure, I watched the evolution of a tangled web of alliances based on power, opportunity, and survival.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, a fellow West Point graduate, summed up his feelings of war more succinctly than many before or since when he said, I hate war as only a soldier who has lived it can, only as one who has seen its brutality, its futility, its stupidity. That is a sentiment not well understood by those outside the military, especially by those indifferent masses who, between meals at the drive-thru, find a spare minute to tie a yellow ribbon on a tree and congratulate themselves for being patriotic. In short, it is not well understood by those who have no idea how to sacrifice or what it means to fight a war that they know isnt right.

This is not a traditional war story. This is not about a black-and-white world, with intrepid American heroes versus murderous villains. Nor is this a story about greedy defense contractors throwing lavish parties with imported alcohol or the hedonism of young State Department workers reveling in the Green Zone. Those stories have been written, and they have been well received. Instead, this is the story of forging alliances and friendships, with money and violence, among the Iraqi people in the alleys of a Baghdad district amid the chaos of war. It is the story of paying people to attend coalition events and council meetings to preserve the pretext that democracy was taking rootlong enough for us to receive promotions and please the politicians. It is a story about moral relativism and changing value systems to accommodate the daily demands of desperate circumstances.

One

HEAVY BUSINESS

RIDING SOUTH ON HIGHWAY 8 out of Baghdad, I scanned the sprawling collection of one-level, sand-colored buildings and their corrugated-steel fences that were cobbled together along the two-lane asphalt highway. In another moment, I could have been driving down the streets in my hometown, where the trailer parks and the junkyards provide a similar backdrop for the hardscrabble scenery. Unlike in Lumberton, Texas, though, in Iraq rusted cars lay beside goats and donkeys, while women draped in black robes from head to toe walked to the market. Here and there, smoke rose from the houses. Gray tendrils from burning trash and pungent compost mingled with household aromas of baking bread and freshly washed laundry. Caught by the breeze, the jumbled odors carried through the open windows of the Humvee. It was not as unpleasant as it was striking.

It was May 2004. I had been in Iraq for two months. Transplanted from my sterile, sanitized life in the United States, I was still overwhelmed by the raw reality of daily life in Baghdad. I had grown accustomed to measuring the severity of my day by the amount of time I spent in traffic or the tone of my bosss latest e-mail. Somehow I had let those banal experiences desensitize me to the magnitude of mans daily struggle, where under sweat-soaked brows he labored strenuously simply to exist. The rising smoke represented a days worka small, successful step forward for all to see. I inhaled the sweet, earthy smell and savored the charcoaled hopes and burning desires that had stoked it into existence. I glanced sideways at a woman and a child struggling to carry an oversized burlap bag of produce to their flimsy roadside market stand. I admired their pride and sense of purpose, traits that had historically made Iraqis resistant to foreign occupation. I needed to find a way to give them hope and patience with the American soldiers and the fledging Iraqi government. If I could not give them a better opportunity to wait for, their determination and willingness to sacrifice would find a ready outlet in the insurgency that was eager to exploit their impatience.

Farther down the road, Iraqi children of all ages played soccer with shiny new balls that American soldiers had handed out during one of our patrols. Marked with logos of professional teams from Europe and America, soccer balls were our most popular item. Hundreds of children would routinely besiege the soldiers and ask for balls to replace the rolls of tape, plastic, and laundry with which they were currently playing. A cloud of dust enveloped the makeshift field as the nylon balls ricocheted erratically across the bare ground between the highway and an abandoned railroad track. The children had not adjusted to the new balls improved buoyancy. Occasionally, the kids would pause long enough to allow herds of goats and their transient herders to pass by. The goats scavenged over the trash caught along the rails and drank from the pools of raw sewage along the roadside. As we passed, the game stopped and a flurry of young hands flailed in the air. The children took turns waving or shooting imaginary weapons at us, depending on whether they were screaming requests or insults. Between the insurgents and the soldiers, the children received so many conflicting messages, they did not know what to believe. At least they had soccer to provide a refuge. In those friendly games no one asked them at gunpoint whom they were playing for or why they were playing. They could be kids without consequence, although, like everything else, that would eventually change.

Next page