Gordon T. Allred is a professor of English at Weber State University in Ogden, Utah, where he has taught for over four decades. He holds a doctorate in creative writing and modern literature and has published 20 books, both fiction and nonfiction, along with numerous short stories and articles. He has received many awards for his writing and teaching, and he recently served on the Hemingway Foundation board of directors. Allred is a fourth-degree black belt in the Kenpo karate system.

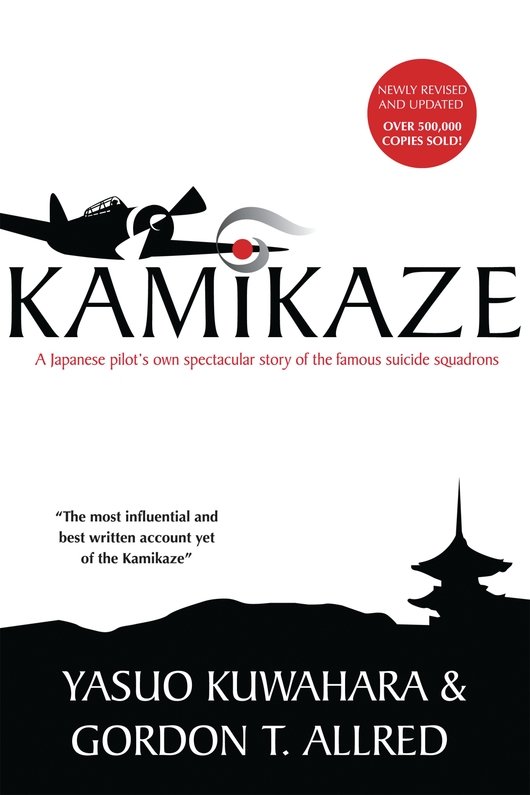

Yasuo Kuwahara was only 15 in 1944 when he won first place at the Japanese National High School Glider contest. As Japans war outlook grew dimmer, Japanese military officers pressed Kuwahara into training as a fighter pilot for the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force. After the war he worked for the U.S. government, and later owned a successful photography business. He died suddenly in 1980.

Chapter One

National Glider Champion

I t is difficult , perhaps impossible, to determine where the forces eventuating in Japans Kamikaze offensive, the strangest warfare in history, began. Ask the old man, the venerable ojiisan , with his flowing beardthe man who still wears kimono and clattering wooden geta on the streetsfor he is a creature of the past. Perhaps he will tell you that these mysterious forces were born with his country over two and a half millennia ago, with Jimmu Tenno, first emperor, descendant of the Sun Goddess, Amaterasu-Omikami. Or, he may contend that their real birth came twenty centuries later, reflected in the proud spirit and tradition of the samurai , the famed and valiant warriors of feudal times.

Whatever their beginnings, these forces focused upon me during 1943, in the midst of World War II, when I was a mere boy of only fifteen. It was then that I won the Japanese National Glider Championship.

Back where memory blurs into veils of forgetfulness I can vaguely discern a small boy watching hawks circle above the velvet mountains of Honshuwatching enviously each afternoon. I remember how he even envied the sparrows as they chittered and flitted through the shrubbery and arched across the roofs. To flytranscend the bondage of gravity! What incomparable freedom! What exhilaration! What joy!

Strangely, even then, I sensed that my future lay somewhere in theskies. At fourteen, attending Onomichi High School, I was old enough to participate in a glider training course sponsored by the Osaka Prefecture, a training that had two advantages. First, it was the chance I had waited for all my lifea chance to be in the air. Secondly, war was reverberating throughout the world, and while many students were required to spend part of their regular school time working in the factories, I was permitted to learn glider flying for two hours every day. All students, in fact, were either directly engaged in producing war materials or preparing themselves as future defenders of their country though such programs as judo, sword fighting, or marksmanship. Even grade school children were taught to self defense with sharpened bamboo shafts.

Our glider training was conducted on a grassy field near the school, and the first three months were often frustrating since we never once moved off the ground. Fellow trainees merely took turns towing each other across the lawn, getting plenty of exercise, while the would-be pilot vigorously manipulated the wing and tail flaps with hand and foot controls, pretending that he was soaring at some awesome height in company with the eagles. Much of our time was also devoted to calisthenics, and it was apparent even then that all of our training was calculated to prepare us for great challenges and trials.

Gradually we began taking to the air, only a few feet above the ground initially, but what excitement! Eventually, thanks to the exertions of a dozen or so young comrades, we were towed rapidly enough to ascend some sixty feet, the maximum height for a primary glider.

Having mastered the fundamentals, we were transferred to the secondary glider, which was car-towed for the take-off and capable of remaining aloft for several minutes. It had a semi-enclosed cockpit and a control stick with a butterfly-shaped steering device for added maneuverability.

Aside from understanding the basic mechanical requirements of glider flying, it was necessary to sense the air currents, feel them out, automatically judging their direction and intensity, like the hawks above the mountains.

How far should I travel into the wind? Often I could determine this only by thrusting my head from the cockpit and letting the drafts cascadeagainst my face. And at times of descent just before I had circled to soar once more upon the thermals the onrushing air tide seemed to have acquired a kind of solidity becoming almost stifling. Moments before take-off, in fact, the air impact was tremendous, nearly overwhelming, requiring all my strength to work the controls.

How far to travel in one direction before circling, precisely how much to elevate the wing flaps to avoid stalling and still maintain maximum height ... these things were not charted beforehand. But the bird instinct was within me, and I was able to pilot my glider successfully, qualifying for national competition the following year.

Approximately six hundred glider pilots throughout Japan, mainly high school students, had qualified for the big event at Mt. Ikoma near Nara and the great city of Osaka. The competition was divided into two phases: group and individual. Contenders could participate in either or both events and were judged on such points as time in the air, distance traveled at a specific altitude, ability to turn within a prescribed space, and angle of descent.

Perhaps it was our intensive training, perhaps destiny, that led six of us from Onomichi High School in western Honshu to the group championship. What glee and wild rejoicing! In addition, two of us were selected from that number for individual competition against about fifty others. I was one of them.

Every contestant was to fly four times, and points accumulated during each flight would be totaled to determine the winner. At the onset I was exceptionally tense and nervous, but such feelings soon faded, and to my immense delight my first three flights seemed almost perfect. Victory was actually in sight!

Sunlight was warming the mountain summit when my final flight commenced. A hundred yards below on the spacious glider field, I steadied myself in the cockpit, feeling a tremor in the fragile structure that held medelicate wood framework, curved and fastened with light aluminum and covered with silk the color of butter cups. The tow rope had been attached to a car ahead, a hook in the other end fastened to a metal ring just beneath the gliders nose. Opening and closing my hand on the control stick, I breathed deeply and concentrated on victory.You can do it, Kuwahara, I told myself, you can do it. Youre invincibleyoure going to win.

Simultaneously my veins, even the tiniest capillaries in my skin, began to tingle. This was the biggest test of my life, a chance to be crowned the greatest high school glider pilot in the Nippon Empire.

My craft lurched and began sliding irresistibly across the turf, and my heart rate increased along with the acceleration. Then I was lifting, confronting the air mass which suddenly seemed immensely heavy and resistant, almost like water. Lifting, lifting ... straining with the controls, feeling disconcerting vibrations. Almost as suddenly, the pressure relaxed, and the bright day itself was bearing me upward. I was above Ikomas calm, green summit, angled sunlight turning the leaves along its western perimeter the colors of polished brass and chrome.