Lee Alan Dugatkin is Professor of Biology and a Distinguished University Scholar in the Department of Biology at The University of Louisville. His books include Mr. Jefferson and the Giant Moose and The Altruism Equation .

Printed by CreateSpace, an Amazon.com company

2011 by Lee Alan Dugatkin

Dugatkin, L.A., 1962

The Prince of Evolution: Peter Kropotkins Adventures in Science and Politics/Lee Alan Dugatkin

ISBN-13 978-1461180173

ISBN-10 1461180171

eBook ISBN: 978-1-61915-528-2

LCCN: 2011908284

For Jerram Brown who believed in me

when there was little reason to.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

{He is} that beautiful white Christ which seems to be coming out of Russia {one} of the most perfect lives I have come across in my own experience.

Oscar Wilde

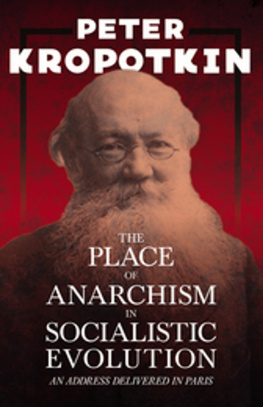

O scar Wilde was not the sort of man prone to effusive compliments. Who could possibly have merited such glowing praise from Wildes typically satirical, razor-edged pen? That perfect life, the White Christ, belonged to a quite remarkable Russian scientist, explorer, historian, political scientist, and former prince by the name of Peter Kropotkin.

Kropotkin was one of the worlds first international celebrities. In England he was known primarily as a brilliant scientist, but Kropotkins fame in continental Europe centered more on his role as a founder and vocal proponent of anarchism. In the United States, he pursued both passions. Tens of thousands of people followed ex-Prince Peterand that is how he was often billedduring two speaking tours in America.

Kropotkins path to fame was unexpected and labyrinthine, with asides in prison, breathtaking 50,000-mile journeys through the wastelands of Siberia, and banishment, for one reason or another, from most respectable Western countries of the day. In his homeland of Russia, Peter went from being Czar Alexander IIs favored teenage page, to a young man enamored with the theory of evolution, to a convicted felon, jail-breaker and general agitator, eventually being chased halfway around the world by the Russian Secret police for his radicalsome might (and did) say enlightenedpolitical views.

Both while in jail, and while on the run when he was entertaining and enlightening huge crowds, Kropotkin found the energy and concentration to write books on a dazzling array of topics: evolution and behavior, ethics, the geography of Asia, anarchism, socialism and communism, penal systems, the coming industrial revolution in the East, the French Revolution, and the state of Russian literature. Though seemingly disparate topics, a common threadthe scientific law of mutual aid, which guided the evolution of all life on earthtied these works together. This law boils down to Kropotkins deep-seated conviction that what we today would call altruism and cooperationbut what the Prince called mutual aidwas the driving evolutionary force behind all social life, be it in microbes, animals or humans. Traveling around the world, and trying to elude the Secret Police, simply gave Kropotkin the time, material and experience to develop his ideas.

Peters theory of mutual aid came to him in the most unlikely of places. To follow in the footsteps of his hero, Alexander von Humboldt, when he was twenty years old, Kropotkin began a series of expeditions in Siberia. At that point, he was already an avowed evolutionary biologistone of the few in Russiaand a great admirer of Darwin and his theory of natural selection. 50,000 miles later, and five years the wiser, Kropotkin left Siberia a Darwinian. But he was a very different kind of evolutionary biologist: a new species of sort. For in Siberia, Kropotkin had not found what he had expected to find.

Though still in its early gestation period when Kropotkin began his journey through Siberia, evolutionary theory of the day advanced that the natural world was a brutal place: competition was the driving force. And so, in the icy wilderness, Peter expected to witness nature red in tooth and claw. He searched for it. He studied flocks of migrating birds and mammals, fish schools, and insect societies. What he found was that competition was virtually nonexistent. Instead, in every nook and cranny of the animal world, he encountered mutual aid. Individuals huddled for warmth, fed one another, and guarded their groups from danger, all seeming to be cogs in a larger cooperative society. In all the scenes of animal lives which passed before my eyes, Kropotkin wrote, I saw mutual aid and mutual support carried on to an extent which made me suspect in it a feature of the greatest importance for the maintenance of life, the preservation of each species and its further evolution.

Kropotkin didnt limit his studies to animals alone. He cherished his time in peasant villages, with their sense of community and cooperation: in these small Siberian villages, Kropotkin began to understand the inner springs of the life of human society. the young scientist witnessed human cooperation and altruism in its purest form.

The conflict then arose in trying to align his observations with Darwinian theory. While he might easily have abandoned evolutionary thinking altogether, joining many other Russian scientists in dismissing Darwins ideas as nothing more than Victorian smoke and mirrors, Kropotkin understood that evolutionary thinking could explain the diversity of life he saw around him. And so he set up the tightrope on which he would balance for the rest of his life. He advocated that natural selection was the driving force that shaped life, but that Darwins ideas had been perverted and misrepresented by British scientists. Natural selection, Kropotkin argued, led to mutual aid, not competition, among individuals. Natural selection favored societies in which mutual aid thrived, and individuals in these societies had an innate predisposition to mutual aid because natural selection had favored such actions. Kropotkin even coined a new scientific term progressive evolution to describe how mutual aid became the sine qua non of all societal lifeanimal and human. Years later, with the help of others, Kropotkin would formalize the idea that mutual aid was a biological law, with many implications, but the seeds were first sown in Siberia.

From the Siberian tundra, Kropotkins thinking turned to the political implications of mutual aid. The ants and termites, the birds, the fish and the mammals were cooperating in the absence of any formal organizational structurethat is without any form of government. The same was true in the peasant villages, where mutual aid abounded, but a centralized government structure was nowhere to be seen. Kropotkin sensed great similarities with the writings of anarchists, which he had taken to covertly as a teenager. Leave people with complete freedom and autonomy, Peter had read in the anarchist literature, and they will naturally cooperate. In Siberia, Kropotkin had discovered this to be true not only for humans, but for all species that lived in groups. What marked so much in the natural world could surely help in politics and society.

I lost in Siberia, Kropotkin would write, whatever faith in State discipline I had cherished before: I was prepared to become an anarchist. In time, Kropotkins ideas on the science of mutual aid would lead to his rise as the most famous anarchist of his day.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS