Pyotr Kropotkin - The Conquest of Bread

Here you can read online Pyotr Kropotkin - The Conquest of Bread full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 0, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

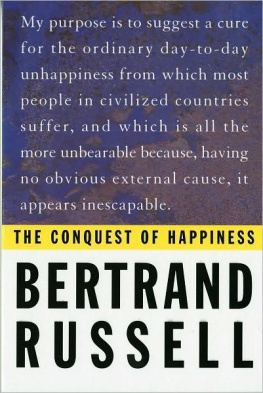

- Book:The Conquest of Bread

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:0

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Conquest of Bread: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Conquest of Bread" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Conquest of Bread — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Conquest of Bread" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

One of the current objections to Communism and Socialism altogether, is that the idea is so old, and yet it could never be realized. Schemes of ideal States haunted the thinkers of Ancient Greece; later on, the early Christians joined in communist groups; centuries later, large communist brotherhoods came into existence during the Reform movement. Then, the same ideals were revived during the great English and French Revolutions; and finally, quite lately, in 1848, a revolution, inspired to a great extent with Socialist ideals, took place in France. And yet, you see, we are told, how far away is still the realization of your schemes. Dont you think that there is some fundamental error in your understanding of human nature and its needs?

At first sight this objection seems very serious. However, the moment we consider human history more attentively, it loses its strength. We see, first, that hundreds of millions of men have succeeded in maintaining amongst themselves, in their village communities, for many hundreds of years, one of the main elements of Socialism the common ownership of the chief instrument of production, the land, and the apportionment of the same according to the labour capacities of the different families; and we learn that if the communal possession of the land has been destroyed in Western Europe, it was not from within, but from without, by the governments which created a land monopoly in favour of the nobility and the middle classes. We learn, moreover, that the medival cities succeeded in maintaining in their midst for several centuries in succession a certain socialized organization of production and trade; that these centuries were periods of a rapid intellectual, industrial, and artistic progress; and that the decay of these communal institutions came mainly from the incapacity of men of combining the village with the city, the peasant with the citizen, so as jointly to oppose the growth of the military states, which destroyed the free cities.

The history of mankind, thus understood, does not offer, then, an argument against Communism. It appears, on the contrary, as a succession of endeavours to realize some sort of communist organization, endeavours which were crowned with a partial success of a certain duration; and all we are authorized to conclude is, that mankind has not yet found the proper form for combining, on communistic principles, agriculture with a suddenly developed industry and a rapidly growing international trade. The latter appears especially as a disturbing element, since it is no longer individuals only, or cities, that enrich themselves by distant commerce and export; but whole nations grow rich at the cost of those nations which lag behind in their industrial development.

These conditions, which began to appear by the end of the eighteenth century, took, however, their full swing in the nineteenth century only, after the Napoleonic wars came to an end. And modern Communism had to take them into account.

It is now known that the French Revolution apart from its political significance, was an attempt made by the French people, in 1793 and 1794, in three different directions more or less akin to Socialism. It was, first, the equalization of fortunes, by means of an income tax and succession duties, both heavily progressive, as also by a direct confiscation of the land in order to subdivide it, and by heavy war taxes levied upon the rich only. The second attempt was to introduce a wide national system of rationally established prices of all commodities, for which the real cost of production and moderate trade profits had to be taken into account. The Convention worked hard at this scheme, and had nearly completed its work, when reaction took the overhand. And the third was a sort of Municipal Communism as regards the consumption of some objects of first necessity, bought by the municipalities, and sold by them at cost price.

It was during this remarkable movement, which has never yet been properly studied, that modern Socialism was born Fourierism with LAnge, at Lyons, and authoritarian Communism with Buonarotti, Babeuf, and their comrades. And it was immediately after the Great Revolution that the three great theoretical founders of modern Socialism Fourier, Saint Simon, and Robert Owen, as well as Godwin (the No-State Socialism) came forward; while the secret communist societies, originated from those of Buonarotti and Babeuf, gave their stamp to militant Communism for the next fifty years.

To be correct, then, we must say that modern Socialism is not yet a hundred years old, and that, for the first half of these hundred years, two nations only, which stood at the head of the industrial movement, i.e. Britain and France, took part in its elaboration. Both bleeding at that time from the terrible wounds inflicted upon them by fifteen years of Napoleonic wars, and both enveloped in the great European reaction that had come from the East.

In fact, it was only after the Revolution of July, 1830, in France, and the Reform movement of 183032, in England, had shaken off that terrible reaction, that the discussion of Socialism became possible for the next sixteen to eighteen years. And it was during those years that the aspirations of Fourier, Saint Simon, and Robert Owen, worked out by their followers, took a definite shape, and the different schools of Socialism which exist nowadays were defined.

In Britain, Robert Owen and his followers worked out their schemes of communist villages, agricultural and industrial at the same time; immense co-operative associations were started for creating with their dividends more communist colonies; and the Great Consolidated Trades Union was founded the forerunner of the Labour Parties of our days and the International Workingmens Association.

In France, the Fourierist Considrant issued his remarkable manifesto, which contains, beautifully developed, all the theoretical considerations upon the growth of Capitalism, which are now described as Scientific Socialism. Proudhon worked out his idea of Anarchism, and Mutualism, without State interference. Louis Blanc published his Organization of Labour, which became later on the programme of Lassalle, in Germany. Vidal in France and Lorenz Stein in Germany further developed, in two remarkable works, published in 1846 and 1847 respectively, the theoretical conceptions of Considerant; and finally Vidal, and especially Pecqueur the latter in a very elaborate work, as also in a series of Reports developed in detail the system of Collectivism, which he wanted the Assembly of 1848 to vote in the shape of laws.

However, there is one feature, common to all Socialist schemes, of the period, which must be noted. The three great founders of Socialism who wrote at the dawn of the nineteenth century were so entranced by the wide horizons which it opened before them, that they looked upon it as a new revelation, and upon themselves as upon the founders of a new religion. Socialism had to be a religion, and they had to regulate its march, as the heads of a new church. Besides, writing during the period of reaction which had followed the French Revolution, and seeing more its failures than its successes, they did not trust the masses, and they did not appeal to them for bringing about the changes which they thought necessary. They put their faith, on the contrary, in some great ruler. He would understand the new revelation; he would be convinced of its desirability by the successful experiments of their phalansteries, or associations; and he would peacefully accomplish by the means of his own authority the revolution which would bring well-being and happiness to mankind. A military genius, Napoleon, had just been ruling Europe.... Why should not a social genius come forward and carry Europe with him and transfer the new Gospel into life?... That faith was rooted very deep, and it stood for a long time in the way of Socialism; its traces are ever seen amongst us, down to the present day.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Conquest of Bread»

Look at similar books to The Conquest of Bread. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Conquest of Bread and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.