I screamed out to the team, Snipers! Snipers behind the tree to our front. Spider hole opening. Bullets tore over our heads as we went to ground. The loud cracks sounded like M-2 carbine fire on full automatic and close. Very close! None of us moved. Then Gary Woodruff, Burns, and I spread out into a firing line, low-crawling to the side where each of us had a lane to shoot down. The platoon behind us had hit the deck and stayed down to let us handle the problem.

Lafley whispered, Wait till he comes up for another shot. Then we drill his ass together. The clicks of our safeties flicking off were drowned out by the rustling of our gear as we settled into position, our rifles trained and our sights on the base of a large tree. As Lafley had predicted, the cover of the spider trap moved and lifted. Seeking a target, the muzzle of a rifle poked from the hole.

Lafley yelled, Now!

A Presidio Press Book

Published by The Random House Publishing Group

Copyright 1999 by John J. Culbertson

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Presidio Press, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Presidio Press and colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

www.presidiopress.com

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 98-93522

eISBN: 978-0-307-55982-1

v3.1

Contents

Prologue

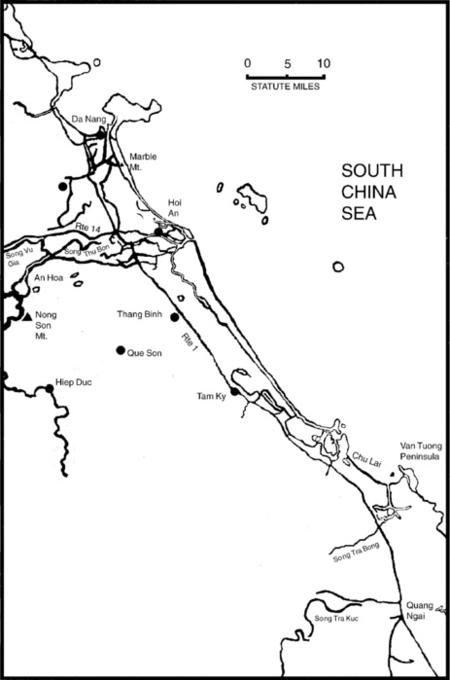

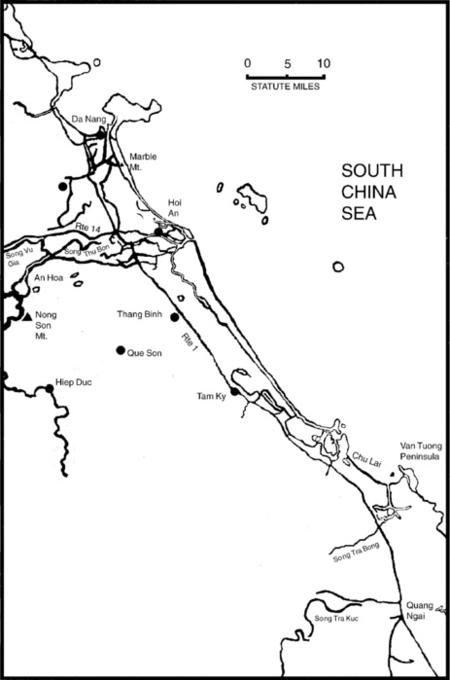

In Operation Tuscaloosa: 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, at An Hoa, 1967, I described how Hotel Company had destroyed the R-20th Main Force Battalion of the regular Viet Cong forces on January 26, 1967, at the river crossing over the Thu Bon River and in assaults against the VC/NVA regulars in the hostile villages of La Bac 1 and 2. Two hundred twenty-one enemy soldiers had been killed or wounded (body count) by the Marines of Foxtrot and Hotel Companies. By January 28, 1967, when Operation Tuscaloosa had been officially secured, the Marines of the 2nd Battalion, based at An Hoa Combat Base, twenty-five miles southwest of Marine headquarters at Da Nang, had sent a clear message to the Viet Cong high command to the north near the Laotian border: the U.S. Marines would press ahead with clearing the hamlets of I Corps of the indigenous Viet Cong terrorists who targeted its peaceful peasant South Vietnamese.

The peasants of South Vietnam themselves were the victims hardest hit by the violence sparked by the military dictatorship of Vo Nguyen Giap in North Vietnams Peoples Republic. For this reason, the Marines had chosen the sensible tactic of fortifying local hamlets using U.S. Marine and South Vietnamese Army (ARVN) soldiers in civil action platoons (CAPs) to clear the countryside of the VC and NVA and to strengthen the local leaders so that they could maintain hegemony within their districts. Offensive strikes like Operation Tuscaloosa were designed to defeat large Communist military units and maintain U.S. superiority on the battlefield. However, victory in large-scale battles like Operation Starlight and Operation Prairie were simply not solely capable of stopping large-scale enemy infiltration into South Vietnam via the Ho Chi Minh trail (particularly into the DMZ, the A Shau Valley, and the Arizona Territory, west of Da Nang).

Operation Prairie I, which ended on January 31, 1967, had lasted 187 days and compiled some significant statistics: a buildup of Marines to over sixty thousand combat and support troops in I Corps; an expansion of U.S. Marine tactical area of responsibility from eight square miles in the beginning of 1966 to one thousand eight hundred square miles at the beginning of 1967; one hundred and fifty combat engagements with enemy forces of at least battalion or regimental strength; the destruction of several enemy battalions (as in Operation Tuscaloosa); the deaths of seven thousand three hundred (body count) enemy soldiers in major operations, with an additional four thousand enemy killed in action (KIA) as a result of over two hundred thousand Marine combat patrols. U.S. Marine losses during the period were one thousand seven hundred KIA and nine thousand wounded.

Despite the enemys catastrophic losses, infiltration into South Vietnam did not let up during 1967; on the contrary, it intensified.

In order to control and pacify the eleven thousand hamlets in South Vietnam, the U.S. and ARVN joint strategy was to present a strong presence by patrolling and village fortification and through the development of the Regional and Popular Forces that comprised the South Vietnamese National Guard. During the early months of 1967, the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, patrolled the Arizona Territory to win the hearts and minds of the local populace. The local populace, on the other hand, would just as soon have sent us on our way back to America, as the war by then had orphaned and widowed many of them. In Hotel Company the grunts still thought the United States could kick Charlies butt (Victor Charlie, i.e., the Viet Cong, our enemy in the Arizona Territory) and win the war.

A Sniper in the Arizona is a true story of the events surrounding Hotel Company and its sister companies in the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division. 2/5 was garrisoned at An Hoa combat base at the southern periphery of the huge rice basin that covered the several hundred square miles in Quang Nam Province, South Vietnam, known as the Arizona Territory. Hotel Company, with the aid of Foxtrot, had just survived a near massacre on the sandbar wastelands of the Thu Bon River during Operation Tuscaloosa. After heavy fighting and maddening losses, the Marines had destroyed their foe in two frontal assaults.

CHAPTER ONE

Tuscaloosa Aftermath

The early weeks of February 1967 brought constant patrolling by Hotel and Foxtrot Companies along the meandering tributaries of the Thu Bon River (Song Thu Bon) deep into the Arizona Territory. The Communist high command in Hanoi was diverting new infantry and support battalions south to press the overall assault on the free Republic of South Vietnam. The invaders were entering South Vietnam through I (Roman numeral for one) Corps, the northernmost of the four military sectors (formally called Corps Tactical Zones or CTZs) of Vietnam controlled by the Allied Forces.

The peasants had seen the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marine (2/5), troops file through the dusty earthen streets of their villages on many occasions in previous months. Yet the old men and mamma-sans were oddly withdrawn and agitated. Something was undercutting the general kindliness the village communities had earlier directed at the Leathernecks. Subtle changes in the mood of the people were important to note in the ever-shifting drama of the jungle war.

Reports of village unease and unfriendliness reached the battalions commanding officer at his headquarters at An Hoa. Lieutenant Colonel Jackson had replaced Lieutenant Colonel Airheart as the battalion CO. Colonel Jackson immediately ordered 2/5s patrols to take Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) interpreters along on any mission through Arizona hamlets expressing hostility toward the Marines.

John Lafley, Luther Hamilton, John Jessmore, and I saddled up for a long patrol that would keep Hotels 3rd Platoon in the bush for several weeks. In Hotel Company, we wore flak jackets and carried small Marine haversacks high on our upper backs. Helmets were worn unstrapped at the chin but low over the eyes to cut down the horrendous glare of the morning sun as it filtered through the trees. Except for FNGs (fuckin new guys), helmet covers were faded camouflage. Our packs contained extra 7.62mm NATO rifle cartridges for our M-14 rifles, socks, cigarettes, and extra C-ration meals. Our jungle boots were white from constant immersion in the water of the paddies that made the Arizona Territory one of the most productive rice-producing valleys in Asia. Our M-14s were spotless. They rested in the crooks of our arms or over the flak-jacket padding of our shoulders. We wore bandoliers of ammo crisscrossed over our chests. Bayonets and K-bar knives hung loosely at the hip.