Copyright 2005, 2012 by John Branson

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com .

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-61608-554-4

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Raymond Proenneke and his late brother, Richard Dick Proenneke for donating the Proenneke journals and slides to Lake Clark National Park and Preserve. Thanks also to Raymond for sharing his knowledge and insights into his brothers life and times.

Many thanks to volunteers in the park, Jeanette and Jerry Mills, for transcribing and proofreading the voluminous hand-written Proenneke journals; and for proof reading my manuscript, many more thanks. Katie Myers, collections manager, and Katie Krasinski, archeologist, did a great deal of photocopying and organizing the Proenneke journals at the Lake Clark-Katmai Studies Center in Anchorage. Molly Casperson, archeologist, scanned the photographs and proofread the print-ready manuscript.

Biological science technician Buck Mangipane and archeologist Dr. Barbara Bundy are due many thanks for the excellent maps of Proennekes world they produced for the book. Other colleagues who are due mention for assisting me with the manuscript are, Dan Young, his wife Amy Sayre, Jennifer Shaw, Chandelle Alsworth, Michelle Ravenmoon, and Angela Olson. Ranger Leon Alsworth has helped me recall details about Proennekes life at Twin Lakes. Editor Thetus Smith and historian Frank Norris at the National Park Service Alaska Support Office in Anchorage also must be thanked for their suggestions on editing the manuscript and on content.

Several friends and neighbors have helped me on this project. For freely sharing their recollections of Richard, thank you very much Margaret Alsworth Sis Clum, Glen Alsworth, Sr., and Laddy and Glenda Elliott. Thanks also to Kimberley McKennett and Danielle Ryman for their help with early versions of the manuscript. Thanks also to Linda Leask, who was a friend of both Richard Proenneke and Helen White; she talked with me about Helen White and proofread the manuscript. Nan Elliott shared her knowledge of Alaska Task Force members and Ed Fortier with me. I am indebted to Denise Martin for her excellent design and layout of the book, and for her patience with revisions of the text.

Finally, I want to thank my supervisors for their steadfast support as I labored on the Proenneke manuscript: former Park Superintendent, Deb Liggett, Park Superintendent Joel Hard, Chief Ranger Lee Fink, and Chief of Cultural Resources and my immediate supervisor, Dr. Jeanne Schaaf.

Preface

Apparently Richard Proennekes journalizing began in the late 1950s or early 1960s while he was spending a month at a remote cabin on Malina Bay on Afognak Island. From his very first visit to Twin Lakes in 1962, Proenneke kept a journal. Over the Twin Lakes years Proenneke wrote millions of words. In 2000 Proenneke and his brother, Raymond, donated all his journals to Lake Clark National Park and Preserve.

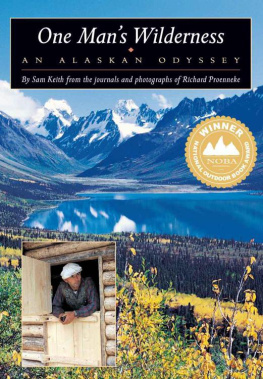

The publication of Proennekes 1968-1969 journals in 1973 as One Mans Wilderness , edited by Sam Keith, was largely responsible for making Proenneke a public figure and putting Twin Lakes on the map as a destination. Proenneke both enjoyed his emerging fame and was dismayed by it. He liked the peace and quiet of Twin Lakes before 1973, but he also enjoyed the public recognition that he was living a rather amazingly inspirational life in the wilds of Alaska. I believe that public acclaim validated in his own mind Proennekes decision to carve out a productive and positive life at Twin Lakes.

Nevertheless, Proenneke was not completely satisfied with Sam Keiths paraphrase of his journals. Proenneke told historian Ted Karamanski in 1990; I think Sam probably... wanted to be an author so I said you just go ahead, I dont care. He [Keith] was editor, but where does author come into it, but the way he wrote it, its pretty much,...he tried to make it sound like it was mine, my thinking...He tried to put words in my mouth. Nevertheless the book was well written and thousands of people have been inspired by it. Overall I think Proenneke was more pleased than not with Keiths version, at the very least it shone the spotlight on what Proenneke felt was a life worth noting.

Soon after the creation of Lake Clark National Park and Preserve in 1980, Proenneke allowed the NPS to copy several years of his journals. In 2000 Proenneke and his brother Raymond were living in retirement in California and they donated nearly 90 lbs. of journals to the NPS. When Proenneke left Twin Lakes for the last time in 2000, he walked away from most everything he owned at the cabin. He left a few items such as his rifle and revolver, a hunting knife, and some clothes to a few close friends, everything else he left to the NPS. As for his cabin, he also left it to the park and I am quite sure he would have done so even if he had title to the land on which it sat. The Proenneke Collection contains journals, letters, calendars, and tools that are part of the park collections at the Lake Clark-Katmai National Park and Preserve Cultural Studies Center in Anchorage.

In 2001 I was asked by my supervisor, Dr. Jeanne Schaaf, to edit the Proenneke journals for publication. Her choice was driven by two factors, my previous historical editing for the NPS and my long time friendship with Proenneke. I think Ive probably spent as much time with Proenneke in the field on long hikes and working together at Lake Clark as anyone alive. I first met Proenneke in June 1976 when Alaska Governor Jay S. Hammond asked him to come to his Lake Clark homestead where I was caretaker to get me and Ralph Nabinger started building a log steam bath.

Proenneke told me in the mid-1990s that I had been on the longest hike he had ever made, from his cabin to the Gills Camp in the Bonanza Hills, some 35 miles. In addition, we hiked to Lake Clark and were together on his last long trek searching for the legendary Chickalusion Pass east of upper Twin Lakes in 1994. We also worked together cutting firewood and logs, clearing land, and harvesting potatoes at Lake Clark.

I am honored to have the opportunity to edit the Proenneke Journals and appreciate the confidence my supervisors have in me. I wanted my edition to be true to Proennekes style but enhanced with explanatory notes, maps, and a biographical sketch of his life. In addition, I wanted to document the creation of a four million acre wilderness national park through Proennekes eyes. During the 1970s the great Alaska lands debate flared across the state and nation and few had such a front row seat or had potentially as much to lose as did Richard Proenneke.

In my conversations with Proenneke during the 1970s I was heartened that he always expressed strong support to preserve the Twin Lakes-Lake Clark country Although I was not then working for the National Park Service I was raised to believe that national parks were very good for our nation and that we ought to have more of them, especially in unspoiled places like Alaska. Having little prior experience with the NPS, Proenneke was initially skeptical that the Service might not have been the best way to preserve the area because he feared national park status would bring far too many visitors who might overwhelm the resources. Gradually he came to recognize that the NPS was the proper institution to preserve and protect Americas special places. While Proenneke second guessed and groused in his journals about some NPS management decisions, I never heard him condemn NPS goals of resource protection and wilderness preservation.

Next page