love saves

the day

2003 Duke University Press

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

Designed by Amy Ruth Buchanan Typeset in Scala and Helvetica by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book.

Second printing, 2004, including minor modifications with regard to Mel Cheren, David DePino, Tom Savarese, Bobby Shaw, and Tony Smith.

contents

Its the last day of a summer visit to Caprarola, Italy. Weve been staying with Enricas grandmanonnaand in the afternoon we visit Aunt Adele and her brother, Father Pietro, who has been working as a missionary in the west African state of Burkina Faso for the last thirty years. I sit next to Pietro, and when he asks me what I do I say that Im writing a book about seventies dance culture. To my surprise his eyes light up and he starts to talk about a new DJing software package he has purchased for his computer. I ask for a demonstration, and as we go upstairs I tell Pietro who is extremely good-humoredthat one of the most important clubs in New York in the early seventies was located in a church and that, according to some, DJs are the new priests. He chuckles. We sit down and Pietro opens OtsJuke DJ, which he uses to program Radio Maria. He starts to play Bob Dylan and segues from Blowing in the Wind into Citt Vuota by the Italian vocalist Mina before rounding off the mix with some quick-fire scratching. He laughs out loud and so do I. Priests, it transpires, are the new DJs.

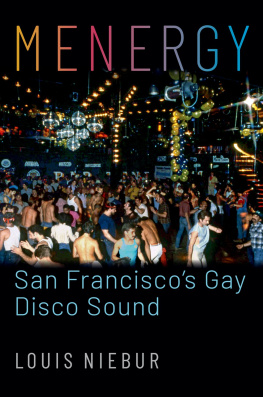

Dance music culture has gone through a remarkable resurrection during the last thirty years. At the end of the 1960s it looked like the American love affair with the French-inspired phenomenon of discotheque had died when the media started to issue obituary notices for a fad that had apparently failed to become a lifestyle. Then, at the beginning of 1970, the Loft and the Sanctuary spawned a new mode of DJing and dancing that went on to become the most distinctive cultural ritual of the decade. Following a roller-coaster ride of adulation and denunciation, club culture has since become a standard feature of the entertainment landscape. Todays dance music infrastructure of mushrooming nightclubs and self-reproducing subgenres enables top-name DJs to charge thousands of dollars for a nights work while international superstars regularly turn to dance producers and remixers for made-to-measure revitalization. Spanning the Americas, Europe, Asia, and Africaincluding Burkina Faso dance culture in its various aesthetic guises has become a global phenomenon.

Even though contemporary practices around DJing techniques, dance floor design, and music aesthetics were largely in place by the end of 1979, the disco decade has yet to receive any kind of sustained examination. A flurry of tongue-in-cheek books appeared at the end of the seventies Albert Goldmans Disco was the best of an indifferent bunchand after a gap of some twenty years the seemingly perpetual seventies revival has produced a handful of additional accounts. Anthony Haden-Guests four-hundred-page account of Studio 54, The Last Party, is typical of this latest wave. Instead of analyzing the dance floor dynamic, Haden-Guest prefers to describe in slobbering detail the designer outfits and drug preferences of every celebrity to descend upon the midtown discotheque, and he becomes so absorbed in pointless anecdotes and name-dropping that he can barely stir up the enthusiasm to reference the clubs principal DJ (who receives a seventeen-word mention). The books treacherously misleading title, which suggests that party culture effectively ended with the closure of Studio 54, must also be news to those who experienced the rapturous reverberations of Body & Soul, the Funhouse, the Loft, the Paradise Garage, the Saint, Shelter, the Sound Factory, and a whole series of other venues that flourished long after Studio 54 had said its goodnights. If only Haden-Guest had bothered to jump in a cab and go downtownwhich is exactly where Love Saves the Day both begins and ends.

At the other end of the publishing market, academic authors have struggled to even acknowledge discos existence. Jacque Attalis compelling Noise, published in 1977, is typical in this respect. Arguing that the combination of specialized training, self-glorifying musicians, and capitalist reproduction was suffocating the music market of the late seventies, the philosopher-economist called for the creation of a new type of collective, improvised, and participatory method of making music. Yet while Attali couldnt have theorized the unfolding discotheque dynamic with any more precision, the DJ-dancer alliance did not find its way into his analysis. Timing might have been a factor: Attali, after all, was writing just a couple of years after disco culture had become visible. But such a line of reasoning would be easier to sustain were it not for the fact that Attalis oversight has since become endemic. In Richard Crawfords otherwise excellent Americas Musical Life, for example, seventies dance musicwhich, like jazz, had many international influences but largely happened in the United States doesnt merit a single reference in nine hundred pages. Perhaps that is because disco is more readily associated with Americas musical death.

That, I must confess, was also my blinkered position before I was introduced to David Mancuso, who at the time was a familiar reference for downtown dance veterans, plus anyone who had come across two distant interviews (one in the Village Voice in 1975 and a second in Collusion in 1983). I didnt qualify on either count, but Stephan Prescottwhod danced at the Loft between 1989 and 1992 before opening Dance Tracks in the East Villagewas edging his way toward veteran status, and he set up an interview with the reclusive party host, whom I met for the first time in a neighborhood Italian restaurant in April 1997. With his big beard, scraggly hair, piercing eyes, and contented potbelly, Mancuso looked like a cross between a disheveled vagabond, a biblical prophet, and a cuddly bear, and he also talked a mystical talk, speaking excitedly in a scrambled code that I could barely follow. By the end of the meal the history of American dance music was less clear than it had ever been, but I was intrigued by his story of a forgotten underworld that ran at a twisted tangent to disco, and as I continued to meet up with better known figures such as Tony Humphries, Frankie Knuckles, and David Morales, I made a point of asking them if they had ever danced at the Loft. Time and time again they would describe Mancuso as their most important influence, a musical messiah who also happened to resemble Jesus Christ. There was clearly more to the 1970s than Ior any other authorhad assumed.

I quickly pieced together an alternative web of house parties and discotheques that could be traced back to the pre-disco era of the Loft and another dance space called the Sanctuary. Yet rather than restrict myself to narrating the evolution of this culture, I decided to trace the lines of influence and interaction that might have flowed between this clandestine party network and the better known celebrity version of disco. What, if any, were the links between the Loft and Studio 54? Did the Sanctuary have anything to do with Saturday Night Fever? And how did downtown relate to midtown and the boroughs? As my research into the Brownian movement of airborne sound waves, freelance DJs, itinerant party hosts, mobile neighborhood populations, and reproducible vinyl records deepened, it became increasingly clear that important connections did indeed exist. Continually cutting across hallowed boundaries, this intricate interaction suggested that no meaningful distinction could be made between the mythically separate cultural terrains of the underground and the mainstream, and that my topography should accordingly cover all aspects of the American nightscape.

Next page