Counselor

A Life at the Edge of History

Ted Sorensen

F OR MY GRANDCHILDREN R ORY , H ANNAH , O LAF ,

L INCOLN , T REY , S OPHIASO THEY CAN KNOW WHAT G RANDPA

T ED TRIED TO DO FOR THEIR WORLD .

SAY NOT THE STRUGGLE NAUGHT AVAILETH

Say not the struggle naught availeth,

The labour and the wounds are vain,

The enemy faints not, nor faileth,

And as things have been, things remain;

For while the tired waves, vainly breaking

Seem here no painful inch to gain,

Far back, through creeks and inlets making,

Comes silent, flooding in, the main.

And not by eastern windows only,

When daylight comes, comes in the light,

In front the sun climbs slow, how slowly,

But westward, look, the land is bright.

A RTHUR H UGH C LOUGH (18191861)

[Written in 1849, from T HE P OEMS AND P ROSE R EMAINS OF A RTHUR H UGH C LOUGH (1869)]

Special thanks to Adam Frankel, a graduate of Princeton University and the London School of Economics, who served as my chief assistant and close collaboratoralmost literally as my eyeson this book for more than six years. His loyalty and dedication made the book possibleand his outstanding research, organizational, and editing skills strengthened it in innumerable ways.

As his friend and admirer, I am confident that Adams many talents will take him far.

T ED S ORENSEN

I wrote this book for three reasons.

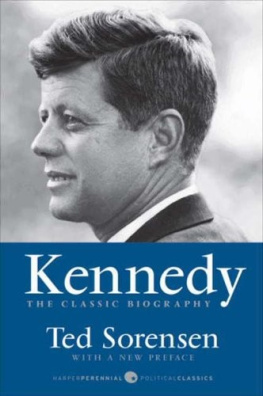

First, when I wrote Kennedy , my 1965 memoir on my eleven years with John F. Kennedy, the pain of his assassination in Dallas still seared my mind; Lyndon Johnson was still president; Robert F. Kennedy was still in politics; Jacqueline Kennedy was still in mourning; and I did not want to offend any of them. The passage of time has made a broader, more candid perspective possible.

Second, a historian recently told me that the history community knows a great deal about Kennedys impact on our nation and world, and something about the impact of my ideas and ideals on Kennedy, but little or nothing about where my ideas and ideals originated. He added: You have an obligation to history to tell us. It reminded me of the 1962 magazine headline: Ted Sorensen: Administration Mystery Man. Perhaps this book can help clear up any remaining mystery. No doubt my story will be weighed in time with many other bits and pieces of informationthat is what history is all about.

Third, disillusioned American citizens today are filled with cynicism and mistrust about presidential politics; most young people today assume that all modern presidents have deceived or disappointed the American people. Perhaps it is worth reminding them that it is possible to have a president who is honest, idealistic, and devoted to the best values of this country. It happened at least onceI was there. In fact, the sorry spectacle of todays national political leadership, so deplorably different from that of JFK, spurred me on while writing this book, rekindling my memory and reinvigorating my conscience.

Yet, as I wrote, I increasingly recognized several major obstacles: (1) the hazards of memory, inevitably influenced by selectivity and hindsight (I was too busy and discreet in both my Senate and White House days to keep a diary); (2) the habit of modesty (this book has required more use of the first-person pronoun than I have ever been comfortable with, but I remember the wisdom of that quintessential American philosopher, baseball great Jerome Dizzy Dean: If you done it, it aint braggin); (3) the obligations of loyalty, which for me outweigh all pressures to cast prudence, privacy, discretion, and the secrets of others aside; and, finally, (4) the limits, both of time and space, requiring me to avoid redundancy and the temptation to meander into every detour and byway. I did not feel footnotes were necessary or appropriate, particularly since the book is intended for lay readers of all ages and not merely for scholars.

After my stroke in 2001, I expressed doubt that, with my eyesight and energy diminished, I would be able to undertake this book. A friendand gifted writeradvised me: Just tell stories. I have always liked telling stories, and have lots of stories to tell. Historian David McCullough has worried that we are losing the national memory of Americas story, forgetting who we are and what its taken to come this far. This book is simply and primarily a collection of one mans memories. It may not fully satisfy either serious historians or sensation seekers. But I hope it will help recall not just my own story, but an inspiring chapter in Americas story.

T ED S ORENSEN

N EW Y ORK C ITY , 2007

One morning in the late 1980s, as the cold war ground to a halt, a distinguished Russian lawyer and former Soviet official, Feodor Burlatski, upon entering my New York City law office, remarked: You and I have corresponded. He being a total stranger, I expressed doubt. But he persisted: Didnt you help draft Kennedys letters to Khrushchev during the Cuban missile crisis? I smiled. Well, he continued, I helped draft Khrushchevs letters to Kennedy. Probably an exaggeration on his part; many others on Khrushchevs staff likely had primary responsibility.

But, in fact, no moment in my life has ever placed more pressure upon me, or ultimately given me greater satisfaction, than the moment late in the afternoon of Saturday, October 27, 1962, when the President of the United States, John F. Kennedy, asked me to draft, with guidance from his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, a letter for the presidents signature to Soviet Council of Ministers Chairman Nikita Khrushchev.

It was the most fateful message I would ever draft. I was thirty-four years old.

October 27 was the twelfth day of what historians have called the most dangerous thirteen days in the history of mankind, the time of the first (and technically only) hostile confrontation between two nuclear superpowers, each possessing the capacity, if not the intent, to incinerate the otherand as a by-product the entire Earth; a crisis precipitated by Khrushchevs swift and reckless decision to emplace in Cuba, ninety miles from our shores, under cloak of deception, a chain of nine bases for more than thirty medium-and intermediate-range nuclear missiles capable of reaching, striking, and destroying tens, even hundreds, of millions of people in the United States and Western Hemisphere.

The presidentonly forty-five years oldhad dispatched his thirty-six-year-old attorney general and me to prepare this letter at the end of an intense debate among his principal advisors, who constituted the Executive Committee of the National Security Council or ExComm, which, while RFK and I sat in my office drafting, was still assembled in the Cabinet Room down the hall, meeting with the president and awaiting our handiwork. Earlier that afternoon, RFK and I had joined Llewellyn Thompson, our countrys foremost Soviet expert and a former U.S. ambassador to Moscow who knew Khrushchev, in urging ExComm and the president to send one letter responding not to each of the two letters received from Khrushchev in the previous twenty-four hours, but only to his first, received on the evening of Friday, October 26. That letter had seemed to convey in part a hopeful tone and, even if obscured, at least the seeds of a potential formula for disengagement. We urged the president to ignore the second letter, which had arrived that same Saturday, October 27, conveying a much stiffer tone, including a demand that the United States on its own (knowing full well that we could not quickly do so) undertake the immediate removal of NATO nuclear missiles situated in Turkey on Soviet borders, in exchange for removal by Khrushchev of his missiles from Cuba. A quarter century later, Kennedys secretary of state, Dean Rusk, wrote me a letter stating that Thompson was the one who originally came up with the idea of ignoring the second message from Khrushchevand responding to the first messagea point which had been discussed with Bobby Kennedy before the meeting in which Bobby Kennedy made that suggestion.