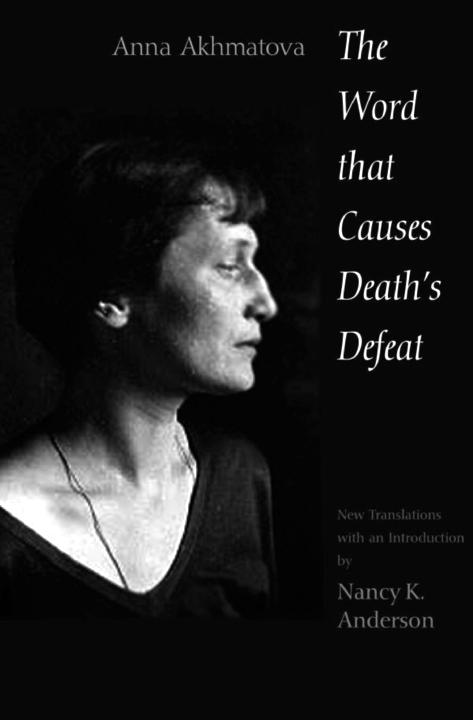

ANNA AKHMATOVA

Translated, with an introductory biography, critical essays, and commentary, by

Nancy K. Anderson

PART I. Biographical and Historical Background

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

Chapter

PART 11. The Poems

PART III. Critical Essays

PART IV. Commentary

Appendixes

Enough has been written about Akhmatova that the addition of another book on her calls for some justification. Perhaps the best way to describe what this book proposes to do is to explain how it came into being.

Some books are the realization of a preconceived plan, like a building constructed in strict conformity with the architect's blueprints. Others, including this one, are like the work of a builder who, as he sees the project begin to take form, suddenly realizes how many possibilities it offers and responds by adding feature upon feature, until the result is a vast elaboration of an initially simple concept.

In the case of this book, the original concept was to offer a new translation of Poem Without a Hero. While Akhmatova's first readers had consistently praised the poem for its musicality, most of the English translations of it I had seen were in free verse, which failed to give any sense of the work's sound or rhythm. The one honorable exception to this rule (at least to my knowledge) is D. M. Thomas's translation. Thomas chose to keep Akhmatova's exact meter while reducing the Poem's end rhymes to assonances (sometimes quite weak ones); I chose to strengthen the stanza structure by keeping the end rhymes (or at least inexact rhymes) while using a meter compatible with, rather than the same as, Akhmatova's.

While the initial idea of translating Poem Without a Hero was straightforward enough, the first addition to the plan occurred almost immediately. Translating the Poem into English, I realized, implied the wish to make it accessible to more than just the limited number of specialists in Russian literature and culture (most of whom, after all, would be able to read the work in the original). But the Poem is such a complex work, and so deeply rooted in the experience of Akhmatova's generation, that a nonspecialist encountering it for the first time might well be disoriented. Accordingly, I decided that guidance was needed, in the form of a critical essay and a commentary The critical essay would discuss the main themes and images, while the commentary would be keyed to individual lines and would identify historical and literary allusions, give variant readings, point out problems of translation, and so on. I intended that every reader should read the critical essay all the way through; the commentary I regard as to some extent optional. Some readers might want to read through it simultaneously with the Poem; others may refer to it only when some individual line baffles them. To make it possible for a nonspecialist to read the commentary straight through, if so desired, I have tried to make it reasonably comprehensive without being overly detailed.

For readers whose ambitions to learn more about Poem Without a Hero had not been sated by the commentary, I included two more sections, which I relegated to the status of appendixes to indicate their optional nature. The first is a translation of the earliest known edition of Poem, written in 1942, some two decades before the final version. The second is a selection of entries from the personal notebooks that Akhmatova kept during the last years of her life, from 1958 to 1966, reflecting her thoughts about the Poem in those years. Both of these sections theoretically could themselves have been the object of further exposition and commentary but because they were included essentially as notes to the Poem, any further comment on them would be glosses on glosses-a form that I found a bit too Talmudic to pursue.

This completed the first round of additions. The second round occurred when I began to think about Poem Without a Hero in the context of Akhmatova's creative biography. Work on the Poem began in 1940, a year that Akhmatova would later speak of as her poetic zenith. Thus I turned to the other works written in that fruitful year in order to determine what recurring themes (if any) could be found, what ideas and emotions were dominant in Akhmatova's artistic consciousness at that time. The year 1940 is associated with two other major works by Akhmatova in addition to Poem Without a Hero: Requiem, parts of which were written earlier but which assumed its definitive form in 1940, and The Way of All the Earth. It soon became clear to me that these poems were united by the theme of memory, the danger of its loss over time, and the will to preserve it.

Requiem grew out of the experience of the Stalinist terror, when many people close to Akhmatova, including her only son, were arrested. As a poem, it responds to this suffering with both a private lyric response and a public epic one. On a purely personal level, the poet-narrator strives to find a way to bear the burden of her constant awareness of her son's ordeal. She is tempted to escape, to forget her pain, whether by simply numbing herself, emotionally distancing herself from a life that is at once agonizingly real and grotesquely unreal, or by the more dramatic means of death or madness. Ultimately, however, she finds the strength to take upon herself the role of witness to suffering and death, as she invokes the image of Mary, the mother of Jesus, standing at the foot of the Cross. This personal act of witness gives rise to a public one, as the grieving mother recognizes her own pain in the face of every woman who lost a loved one to the Terror and accepts the responsibility to speak for all those who are too frightened or crushed in spirit to tell their own stories. The poet cannot save the victims; but through her conscious act of memory, through the creation of a poem that serves as a monument to them, she can prevent the second death that would occur if they were forgotten.