All facts, description, and even dialogue in these pages are drawn entirely from the historical record. This story may at times seem improbable, but it is true.

U NTIL THE INVENTION of the internal combustion engine, the most prolific traveler in history was also the most unlikely. Born in 1786, James Holman was in many ways the quintessential world explorer: a dashing mix of discipline, recklessness, and accomplishment, a Knight of Windsor, Fellow of the Royal Society, and bestselling author. It was easy to forget that he was intermittently crippled, and permanently blind.

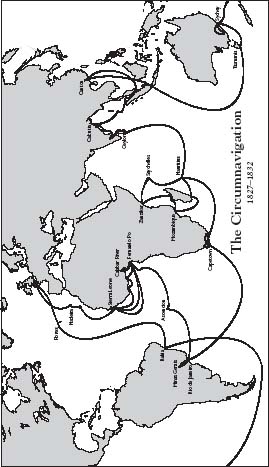

He journeyed alone. He entered each country not knowing a single word of the local language. He had only enough money to travel in native fashion, in public carriages and peasant carts, on horseback and on foot. Yet he traversed the great globe itself more thoroughly than any other traveler that ever existed, as one journalist of the time put it, and surveyed its manifold parts as perfectly as, if not more than, the most intelligent and clear-sighted of his predecessors.

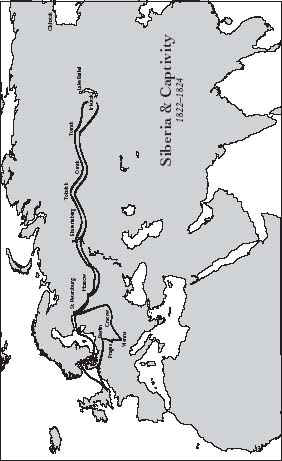

In an era when the blind were routinely warehoused in asylums, Holman could be found studying medicine in Edinburgh, fighting the slave trade in Africa (where the Holman River was named in his honor), hunting rogue elephants in Ceylon, and surviving a frozen captivity in Siberia. He helped unlock the puzzle of Equatorial Guineas indigenous language, averting bloodshed in the process. In The Voyage of the Beagle , Charles Darwin cites him as an authority on the fauna of the Indian Ocean. In his commentary on The Arabian Nights, Sir Richard Francis Burton (who spent years following in Holmans footsteps) pays tribute to both the man and his fame by referring to him not by name, but simply as the Blind Traveler.

James Holman was justly hailed as one of the greatest wonders of the world he so sagaciously explored. But astounding as his exploits were, a further astonishment is how quickly he was forgotten. The publics embrace, driven more by novelty than genuine respect, did not endure. Critics dismissed his literary and scientific ambitions as something incongruous and approaching the absurd. One bitter enemy, another professional adventurer whose expedition was eclipsed by Holmans, leveled a charge that took root in public perception: His sightlessness made genuine insight impossible. He might have been in Zanzibar, but how could the Blind Traveler claim to know Zanzibar? He was rarely doubtedhis firsthand facts were unassailably accuratebut he was increasingly ignored.

The fame diminished, and curdled into ridicule, but Holman didnt slow down in the slightest. Impoverished, increasingly threadbare, and still in debilitating health, he kept to his solo travels, even as his works fell out of print and his new writings went unpublished. His few steadfast admirers lost track of him, presuming him dead in some distant corner of the globe. His true end came suddenly, in a scandalously unlikely corner of London, interrupting both his fervent work and plans for further voyages.

Holman dreamed that future generations might appreciate his lifes work, but they werent given the chance. His eclectic collection of artifacts was scattered and discarded, his manuscripts destroyed or lost. If he could be said to have a monument at all, it was a brief biographical sketch in the Encyclopedia Britannica, an entry that dwindled in subsequent editions. By 1910, it was a single paragraph. By 1960, it had disappeared altogether.

M Y OWN JOURNEYS in Holmans faded footsteps began three years ago, with a flash of turquoise. Like most writers who work self-sequestered in the halls of a library, I was in the habit of taking wander breaks. Id weave idly through the aisles, pick out a book at random, and leaf through it for ten minutes or so before getting back to work. Usually it was the title that caught my eye My Life as a Restaurant , Caring for Your Miniature Donkey but one afternoon I was drawn to a small book more by its bright turquoise spine than its title, which was Eccentric Travelers .

It was an aptly named book, with one important exception. Eccentric Travelers profiled seven wanderers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, most indisputably crackpots. One moonlighted as an exorcist. Another brought back hoaxed specimens of fictional animals. But despite the fact that sightlessness hardly qualifies as an eccentricity, there was also a chapter on the Blind Traveler. Slim as it was, the volume had apparently needed some filling out.

It was only a brief, frustratingly incomplete profile, but it was that incompleteness that drew me in. I launched a search for a book devoted to this singular individual, a search that started with adjacent shelves and continued to escalate over the course of several weeks, until it was clear that no such book existednot in any library, in any language. That single chapter in the little turquoise book was, I would discover, the most extensive writing on the Blind Traveler ever published.

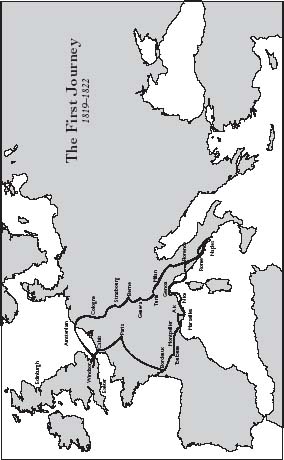

I managed to track down a few volumes of Holmans own writings, antiquarian rarities, but reading them only tantalized me further. His published work begins in 1819 and ends abruptly in 1832, leaving most of his life effectively veiled in silence. Even these surviving narratives are notably lacking in autobiographical detail. He does not explain his blindness, because it was an enigma even to himselfthe final symptom of a mysterious illness that struck him in his early twenties. He is, uncharacteristically for a professional adventurer, seemingly incapable of self-promotion, racking up a series of unprecedented achievements but almost never bothering to note them as such. He is also discreet to a fault, obscuring most of the identities of people he encounters during his adventuresespecially those of women, who were drawn to him, and whose attentions he returned with gentlemanly ardor.

A medical mystery, a modest hero, a series of cloaked affections. How could my fascination not become an obsession, and finally a quest? I went to England, to decipher the faded ink of ships logs, and brush the crumbling wax from broken seals of once-secret documents from Windsor Castle. I traced the fate of the Holman River, long disappeared from maps, and of the African settlement hed helped to found (now the capital of a sovereign nation). After a century and a half of obscurity, the full tale of the Blind Traveler began to emerge. It proved to be even more extraordinary than I could imagine.

James Holman was a whirlwind of incongruities: an intrepid invalid (at times simultaneously incapable of standing up and standing still), a poet turned warrior turned wanderer, a solitary man who remained deeply engaged with humanity. His adventures were neither acts of machismo nor self-aggrandizing stuntsthey were, as he put it, a means to enter into the business of lifecommunion with the world and its multiplying delights.