Published in 2017 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2017 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

First Edition

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

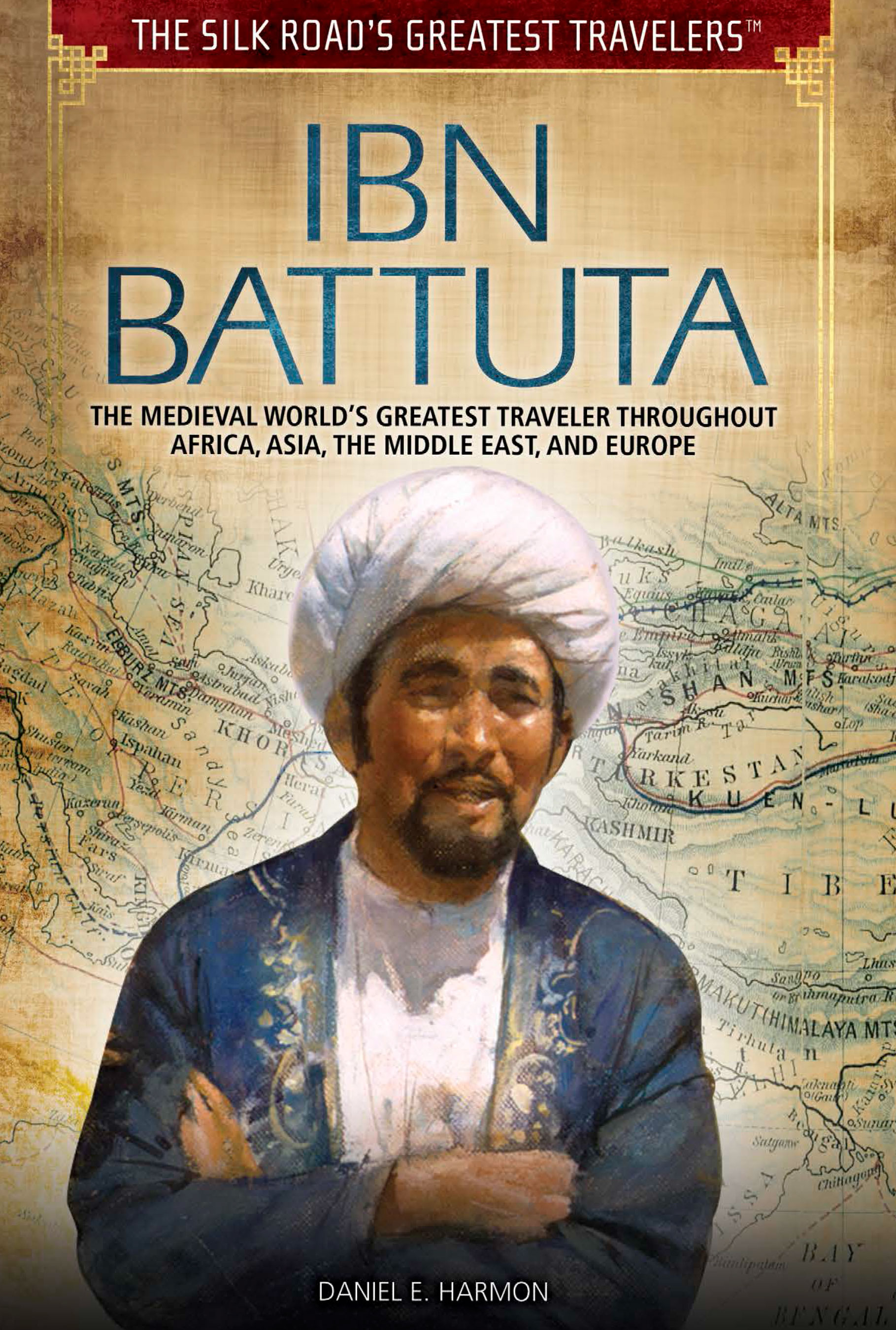

Names: Harmon, Daniel E.

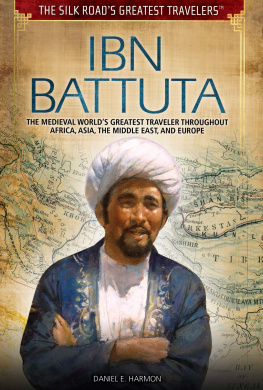

Title: Ibn Battuta : the medieval world's greatest traveler throughout Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Europe / Daniel E. Harmon. Description: New York : Rosen Publishing, 2017. | Series: The Silk Road's greatest travelers | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015048427 | ISBN 9781508171508 (library bound) Subjects: LCSH: Ibn Batuta, 1304-1377--Travel--Juvenile literature. | Travelers--Islamic Empire--Biography--Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC G93.I24 H37 2017 | DDC 910.92--dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015048427

Manufactured in China

H e was a man who felt truly blessedfor the moment. Ibn Battuta, a wealthy adventurer and religious scholar from Morocco, had been away from home for many years by the middle of the fourteenth century. He had made the difficult pilgrimage to Medina and Mecca, a trip required of Muslims of his class. He then had traveled much farther. Ibn Battuta had visited mysterious lands hundreds of miles to the north and south of the Islamic holy cities. Eventually, he hoped to reach the Far East. He was captivated by stories of the Orients fabled riches.

Ibn Battuta now found himself in the Indian port of Calicut. He had earned the favor of the sultan at Delhi. The sultan was sending him on a spacious junk (East Asian ship) as an ambassador to China.

Just before he was to sail away with his attendants, provisions, and gifts for the Chinese emperor, a powerful storm swept across the harbor. Ibn Battuta watched helplessly from shore as ships were driven onto the beach and battered to pieces in the pounding surf. Almost all of his party, including slaves and pages, were drowned, as were their horses and other livestock. Almost as demoralizing was the loss of the precious wares he was supposed to present to the ruler in China.

Ibn Battuta was alive, but he had lost everything. He was afraid to return to the sultans court, fearing he might be executed because of his failed mission. He decided to make his way in a different direction. Perhaps he could befriend another sultan who would help him on his way.

Ibn Battuta would reach his destination. But it would be a much longer, harder, and more perilous experience than he expected. His meandering routeIbn Battutas contribution to the complex Silk Road of historywould lead him through events and situations he never envisioned. He was in for many more ups and downs. He would become involved in warfare and trading schemes. He would survive epic treks through brutal terrain and tumultuous sea passages. Luxurious delights would be mingled with severe hardships.

Ibn Battuta was one of the most ambitious and determined travelers of the Silk Road. Based on his records, scholars estimate his lifelong journeys covered no fewer than 75,000 miles (120,700 kilometers). If their calculations are accurate, the total distance of his movements by boat, camel, and foot could have circumvented the earth around the equator three times.

He was a charismatic and clever man. Ibn Battuta made countless friends during his travels and became quite wealthy and influentialand lost it all more than once. Because of the knowledge he accumulated about Muslim history and laws, he was greatly respected by the Muslim rulers he visited. The favor he received from them brought him riches and personal pleasures. Ibn Battuta was married at least seven times during his journeys, probably more than ten.

Ibn Battuta came to be regarded as a scientist as well as a world traveler. His geographical records helped fill in the pieces of a mysterious world (which at the time was thought to be flat). It was a world in which people of different regions knew little or nothing about what lay over the horizon. They were unacquainted with other cultures. More than any other explorer of his era, Ibn Battuta helped make intracultural introductions.

T he Silk Road is a term that is badly misunderstood by many people. To those with only a vague understanding, it brings to mind a long, dusty trail between Romethe ancient center of Western civilizationand China. It crossed seemingly endless desert sand dunes, bleak steppes, and rugged mountains. This fabled road brought caravans laden with silk from China to Arabian and European ports and capitals.

In reality, the Silk Road was a complex network of trade routes connecting the far-flung market centers of several continents. Few traders from Europe made it anywhere near China, and few from China came farther west than Persia (modern Iran). Rather, they traded at much shorter distances. But some of the goods they carried, after passing through many hands, reached consumers thousands of miles from their points of origin.

Goods have been traded among East Asian, Indian, and Mediterranean civilizations for several thousand years. Until the modern era, Arabia and Persia were at the heart of much of it.

Trade along Silk Road routes began to enter a golden age in the eighth century when Harun al-Rashid established the Abbasid dynasty, based in Baghdad. Prosperity produced by Silk Road trade began to wane in the fourteenth centuryabout the time of Ibn Battuta. The Ottoman Empire took over control of overland trade between the East and West and held it for six centuries. Meanwhile, improvements in shipbuilding and navigation gradually made sea routes preferable to the long caravan trails. A large merchant ship could stow more cargo in its hold than the largest camel caravans could transport.

TRAVEL ALONG THE SILK ROAD

To carry their wares, traders used camels, donkeys, and other pack animals. Where the terrain permitted, they loaded merchandise in carts pulled by oxen or horses. At times, merchants rode camels or horses. More often, they walked, using the animals to haul cargo. Over time, transportation improved with the development of harnesses and other gear for controlling the animals.

Camels were preferred for transport, especially in the deserts. They needed little food and could function for days at a time without water. Camels could carry heavier loads than horses and could haul them as far as 20 miles (32 km) each day.

Along the way were caravanserai, inns where merchants and adventurers could rent a bed, rest, and dine more comfortably than they could camping on the trail. Travelers from different cities and cultures relaxed around the open fires, trading stories of their experiences. Some of the caravanserai were small fortresses with walls and gatesprotection from marauding bandits and natural elements. Travelers also came across numerous open-air bazaars. There, if bargains could be struck, they added to the merchandise they were transporting.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)